© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 7/2010, s. 537-545

*Jacek Gronwald1, Tomasz Byrski1, Tomasz Huzarski1, Oleg Oszurek1, Jolanta Szymańska-Pasternak1, Bohdan Górski1, Janusz Menkiszak2, Izabella Rzepka-Górska2, Jan Lubiński1

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

Genetyka kliniczna raka piersi i jajnika

1International Hereditary Cancer Center

Head of Department of Genetics and Pathology: prof. zw. dr hab. med. Jan Lubiński

2Pomeranian Medical University

Department of Surgical Gynecology and Gynecological Oncology of Adults and Adolescents

Head of Department of Surgical Gynecology and Gynecological Oncology of Adults and Adolescents: prof. dr hab. med. Izabella Rzepka-Górska

Streszczenie

W ostatnich latach udało się wykazać u niemal wszystkich pacjentów z rakami piersi lub jajnika charakterystyczne podłoże konstytucyjne sprzyjające rozwojowi tych nowotworów. Stwierdzono, że nosicielstwo mutacji w genach BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, NBS1, NOD2, CDKN2A, CYP1B1, jak i rzadziej występujących zmian w genach takich jak ATM, PTEN, STK11 wiąże się z podwyższonym ryzykiem raka piersi. Zaburzenia w genach BRCA1, BRCA2, NOD2, CHEK2, DHCR7 predysponują do rozwoju raka jajnika. W niektórych przypadkach zmiany genetyczne wiążą się z bardzo wysokim ryzykiem nowotworowym, w innych przypadkach wykrywane zaburzenia predysponują do rozwoju raka w mniejszym stopniu. Zdiagnozowanie podwyższonego ryzyka raka umożliwia wdrożenie programu profilaktycznego umożliwiającego zapobieżenie nowotworowi, a tam gdzie to się nie udaje pozwala na wykrycie raka we wczesnym stadium. Dodatkowo zdiagnozowanie nosicielstwa odpowiednich mutacji pozwala na dobór najefektywniejszego, zindywidualizowanego sposobu leczenia związanego z uwarunkowaniami konstytucjonalnymi pacjenta. Dużym problemem diagnostycznym są pacjentki, u których zmian molekularnych nie udało się znaleźć, ale dane rodowodowo-kliniczne wskazują na silne podłoże genetyczne nowotworu. W niniejszym opracowaniu przedstawiono podłoże genetyczne rozwoju raka piersi i jajnika uwzględniając wpływ genów wysokiego oraz umiarkowanie zwiększonego ryzyka jak i zasady interpretacji danych rodowodowych. Omówiono obecnie obowiązujące zasady diagnozowania grup ryzyka, profilaktyki oraz leczenia raka u pacjentek z zespołem BRCA1, BRCA2, BRCAX oraz ze zmianami w genach umiarkowanie zwiększonego ryzyka.

Summary

Familial breast cancer was first recognized in the Roman medical literature of 100 AD (1). The first documentation of familial clustering of breast cancer in modern times was published by Broca, who reported 10 cases of breast cancer in 4 generations of his wife's family (2). In the middle of nineties it was proven at molecular level that substantial number of breast and ovarian cancers has hereditary monogenic etiology (3, 4). Evaluation of frequency of pedigree-clinical signs characteristic for strong aggregations of breast/ovarian cancers among consecutive cases of cancers of these organs as well as analyses of cancer incidence in monozygotic tweens indicate that about 30% of breast and ovarian cancers develop because of strong genetic predisposition (5). In other breast/ovarian cancers significance of genetic factors was underestimated. However, recently it was possible to show characteristic constitutional baground influencing development of cancer also in patients with sporadic neoplasms. Therefore now, scientists think that in almost all patients with cancer a certain genetic backgroung should be detectable although influencing cancer risk with different degree. Genetic abnormalities strongly related with cancer are called high risk changes (genes) and abnormalities influencing cancer development with lower degree are called moderate risk changes (genes). Most frequently strong genetic predisposition to breast/ovarian cancers are related to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and most often it apeares as syndromes of hereditary breast cancer – site specific (HBC-ss), hereditary breast-ovarian cancer (HBOC) and hereditary ovarian cancer (HOC).

In family members of families with HBC-ss syndrome only breast cancers but not ovarian cancers are observed. In HBOC syndrome families with both – breast and ovarian cancers are diagnosed and in HOC syndrome only ovarian but not breast cancers are detected. Operational clinical-pedigree criteria which we use in order to diagnose "definitively” or "with high probability” the discussed syndromes are summarized in table 1. In vast majority of cancer cases related to moderate risk genes family history is negative. HBC-ss, HBOC, HOC syndromes are clinically and molecullary heterogenous. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are the most frequent cause of these syndromes.

Table 1. Pedigree-clinical diagnostic criteria of HBC-ss, HBOC and HOC syndromes (6, 7).

| Number of breast or ovarian cancer cases in family: |

A - 3 (definitive diagnosis)

1. At least 3 relatives affected with breast or ovarian cancer diagnosed at any age. |

B - 2 (highly probable diagnosis)

1. 2 breast or ovarian cancer cases among Io relatives (or II° through male line);

2. 1 breast cancer and 1 ovarian cancer diagnosed at any age among Io relatives (or II° through male line). |

C - 1 (highly probable diagnosis)

1. breast cancer diagnosed below 40 years of age;

2. bilateral breast cancer;

3. medullary or atypical medullary breast cancer;

4. breast and ovarian cancer in the same person;

5. breast cancer in male. |

BRCA1 syndrome

In this syndrome women carry a germline mutation in the BRCA1 gene. Carriers of a BRCA1 mutation have approximately 50-80% life-time risk of breast cancer and 40% risk of ovarian cancer (18). We estimate that these risks are 66% for breast cancer and 44% for ovarian cancer in the Polish population (tab. 2). Both risks appear to be dependent on the type and localization of the mutation (19, 20, 21). Our findings suggest that the risk of breast cancer in women with 5382insC is two times higher than in women with 4153delA. It is observed positive correlation between type of cancer in family and risk of this cancer for other family members (75).

Table 2. Risk of breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers in Poland (11).

| A: Cumulated risk of breast cancer: |

| Age: | <30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 75 |

| Cumulated risk (%): | 1.6 | 6.5 | 30 | 40.5 | 50,5 | 66 |

| B: Cumulated risk of ovarian cancer: |

| Age: | <30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 75 |

| Cumulated risk (%): | 1 | 3.5 | 12 | 30 | 41 | 44 |

Incomplete penetrance of BRCA1suggests that other factors, genetic and non-genetic modifiers are important in carcinogenesis in the mutation carriers. The risk of ovarian cancer is modified by VNTR locus for HRAS 1 – is increased 2-fold in BRCA1carriers harboring one or two rare alleles of HRAS 1 (22). We reported that the 135G>C variant in RAD51 gene is strongly protective (OR = 0.5) against both ovarian and breast cancer (23, 24).

Carriers of a BRCA1 mutation are also at about 10% life-time risk of fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers (13). This data about the frequency of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 carriers appear to reflect combined frequency of ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers, because these tumors were diagnosed as ovarian cancers in the past, and because they share similar morphology and cause elevated levels of marker CA 125.

The risk of cancer at other sites may be increased in carriers of a BRCA1 mutation as well, but the evidence is controversial and need further studies.

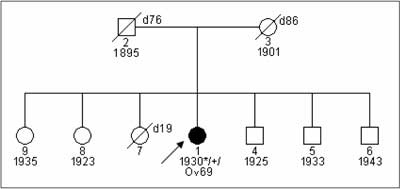

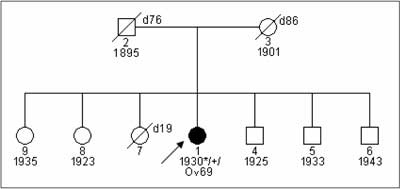

Breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA1 carriers have particular clinical characteristics. The mean age at onset of breast cancer is about 42-45 years (26, 27) and of ovarian cancer is about 54 years (6, 28). 18-32% of breast cancers are bilateral (29, 30). These are rapidly growing tumors:>90% of cases have G3 grade at the time of diagnosis and almost all ovarian cancers in women with a BRCA1mutation are diagnosed in FIGO stage III°/IV°. Medullar, atypical medullar, ducal breast cancers are common in BRCA1 carriers. These tumors are most frequently "triple negative” – they do not show expression of estrogen, progesteron and herceptin receptors (ER-, PGR-, HER2-) (31, 32, 33). Most carriers of a BRCA1 mutation report a positive family history of breast or ovarian cancer (fig. 1, 2). However, 45% of BRCA1 carriers report a negative family history, mainly because of paternal inheritance, incomplete penetrance and low number of children in families from industrial countries (fig. 3) (30).

Fig. 1. Family with HOC syndrome and diagnosed constitutional 4153delA BRCA1gene mutation.

Fig. 2. Family with fulfilled clinical-pedegree criteria „suspected HBC-ss”. BRCA1mutation was not detected.

Fig. 3. Patent with ovarian cancer and detected 5382insC BRCA1 mutation from family with negative family history.

Molecular diagnosis of constitutional BRCA1 mutations

This topic has been described in detailes in chapter „Test BRCA1”.

BRCA2 syndrome

Patients with this syndrome have constitutional mutation in BRCA2 gene (34). According to literature data life time risk for BRCA2 carries from families with definitive HBC-ss and HBOC is estimated on 31-56% for breast cancer and 11-27% for ovarian cancer (20, 35, 36, 37, 38). Studies performed in 200 Polish families with strong aggregation of breast and/or ovarian cancers proved that mutations in BRCA2 gene are rare with the frequency of 4%. There are no studies on cumulated cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers form Polish population. Most BRCA2 mutations from Polish population most probably slightly increase breast cancer risk. Studies performed in our center showed that in families with aggregation of breast cancer diagnosed before age of 50 and stomach cancer diagnosed in males before age of 55 frequency of BRCA2 carriers is about 10-20% (39). BRCA2 mutations are related also with significantly increased however not precisly estimated risk of ovarian cancer and cancers of digestive tract as stomach, colon, pancreas both in females and males. Studies performd in our center showed BRCA2 mutation are detected with frequency of 30% in families without breast cancer but with aggregation of ovarian cancer with stomach, colon or pancreatic cancer between first and second degree relatives (40). BRCA2 studies performed on male breast cancer patients from Poznań population showed that 15% of patients from this group are mutation carriers (41).

Breast and ovarian cancers in families with BRCA2 mutations have characteristic features. Medium age of breast cancer is 52 and 53 in females and males, respectively and 62 of ovarian cancer (41, 42).

Molecular diagnosis of BRCA2 mutations

Differently like for BRCA1 gene, founder effect for BRCA2 mutations was not observed with significant frequency in Polish population (32). It should be noted that mutations "de novo” are rare in these groups of genes, thus the presence of founder mutations in BRCA2 is probable. Up to now BRCA2 mutations should be diagnosed individually for each family by full sequencing. Since BRCA2 gene is large – about 70 genomic kbp – the cost of sequencing of his gene is high (around 1500 euro). Reasonable alternative technology for sequencing should be sequenom technology (see chapter – "Test BRCA1”).

In families with detected marker constitutional mutation the cost of analysis of two independently taken blood samples allowing exclusion or confirmation of carrier status among relatives is low – around 100 euro.

BRCAX syndrome

In Poland in about 30% of families with definitively diagnosed HBC-ss and HBOC syndromes and in about 40% of families with HOC syndrome, BRCA1or BRCA2mutations are not detected. In rare cases it is possible to diagnose one of rare syndromes listed in table 3. In these syndromes breast/ovarian cancers are observed with higher frequency. Many groups in the world try to identify new genes causing BRCAX syndrome.

Table 3. Selected rare syndromes with increased risk of breast and/or ovarian cancer.

| Disease | Clinics | Gene mutation/Inheritance | Referencer |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | breast cancers, sarcomas, brain tumours, leukemia, arenal gland cancer | p53, high penetrance; AD | 17, 33 |

| Bowden disease | multifocal mucoid skin abnormalities, benign proliferative abnormalities of different organs, thyroid cancers, breast/ovarian cancers | PTEN AD | 34, 35 |

| HNPCC | colon cancers, endometrial cancers, other organ cancers including breast and ovary | MSH2, MLH1; AD | 36 |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | hyperpigmentation of the mouth, bowel polyps, colorectal cancers, small bowel cancers, gonadal tumors, breast cancers | STK11; AD | 37 |

| Ruvalcaba- Myhre-Smith (Z.Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba) syndrome | macrocephaly, bowel polyps, "café-au-lait" on penis, lyphomas, thyroid cancers, breast cancers | PTEN AD | 38 |

| Heterozygotic carrier status of "ataxia telangiectasia" gene | Ataxia of cerebellum, ocular and skin, hypersensitivity for radiation, different site neoplasm including breast/ovarian cancer | ATM | 39 |

| ATH gene carriers | Increased breast cancer risk | low penetrance 20-40%; AD | 6 |

| Klinefelter syndrome | Gynecomastia, cryptorchidism, extragonadal germ cell tumors, male breast cancer | 47, XXY; low penetrance < 10% | 40 |

| Androgene receptor gene mutation | Familial male breast cancer | Androgene receptor | 41 |

| Constitutional translocation t(11q;22q) | Increased breast cancer risk | balanced translocation t(11q;22q) | 42 |

Inheritance:

AD - autosomal dominant

AR - autosomal recessive |

Clinical management in families with high risk of breast/ovarian cancer

Special management should be applied for:

– carriers of mutations of high breast/ovarian cancer risk; usually around 50% of female family members shoud be included into program,

– all family members of families with HBC-ss, HBOC, HOC diagnosed definitively or with high probability according to pedigree criteria shown in table 1, if constitutional mutations predisposing to cancer were not detected.

Special management concerns:

a) prophylactics;

b) surveillance;

c) treatment.

Ad. a. Prophylactics

Oral conrtaceptives

Contrindications for using oral contraceptives (OC) by BRCA1 carriers at age below 25 are well documented. It was shown that OC used for 5 years by young women increase breast cancer risk about 35% (43). Since in about 50% of BRCA1 carriers family history is negative it seems to be necessary to performe BRCA1 test in every young woman who wish to use OC. OC used by BRCA1 carriers after age of 30 seem to do not influence breast cancer risk (43, 44, 45) but show 50% reduction of ovarian cancer risk (8), so, using of OC after age of 30 seems to be justified. Up to now, there are no verified data concerning effects of OC in families not related to BRCA1 mutation. However, there are studies indicating several fold increased breast cancer risk in OC users from families with breast cancer aggregation (46), thus it seams reasonable to avoid OC in families with HBC-ss and/or HBOC.

Hormonel replacement therapy (HRT)

Prophylactic oopherectomy at age of 35-40 is gold standard for BRCA1/2 carriers and corresponds with risk reduction for both breast and ovarian cancer. It was shown that carriers after oopherectomy, who use estrogen HRT show similar protective effect like patients who do not use HRT (47, 48). Influence of HRT in carriers without prophylactic oopherectomy is not well documented. 3-fold increased risk of breast cancer in HRT users with positive breast cancer family history was reported (49). Therefore, decision about HRT use shoud be taken with particular caution.

Breast feeding

Long term breast feeding is indicated in all females from families with HBC-ss, HBOC and HOC. It was shown in BRCA1 carriers that breast feeding over 18 months, counting togother all pregnancies, is reducing breast cancer risk – from 50-80% to 25-40% (50, 51).

Early delivery

Women from general population who delivered the first child before age of 20 are of 50% lower breast cancer risk than nullparous women. This observation was not confirmed in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation (52). However taking into consideration the fact that mutation carriers should elect prophylactic oopherectomy at age of 35-40, they shold not delay maternity significantly.

Chemoprevention

Tamoxifen

Literature data cleary indicate that tamoxifen decreases about 50% risk of ER+ breast cancers. This effect was observed in healty women as well as in women treated because of breast cancer where tamoxifen decreased risk of contralateral breast cancer. Protective effect of tamoxifen was observed also in BRCA1carriers in spite of the fact that most cancers in these patients are ER-. Such effect of tamoxifen was observed in pre- and postmenopausal women (53, 54). According to present data it is justified to propose 5 year chemoprevention with tamoxifen to patients from families with HBC-ss, HBOC and BRCA1mutation carriers as well after exclusion of all contraindications especially related to clotting problems and endometrial hypertrophy.

Selenium

Studies performed in our center showed increased mutagene sensitivity in BRCA1 carriers as measured with bleomycine test. This sensitivity may be normalized with some of selenium supplements (55). It has been shown that level of selenium in serum may be important factor influencing breast or ovarian cancer risk between BRCA1 carriers (data not published).

Adnexectomy

Both retrospective and prospective observations of patients with BRCA1/2 mutations indicate that prophylactic adnexectomy decreases the risk of ovarian/peritoneal cancer to about 5% and breast cancer to 30-40%. Application of adnexectomy togother with tamoxifen reduces brast cancer risk to about 10% in BRCA1 carriers (25). Therefore, in our center adnexectomy is recommended to all BRCA1/2 carriers at age over 35. This surgery is proposed to women from families with HBC-ss, HBOC and HOC but without detected BRCA1//BRCA2 mutation only if other pathologies of femal genital tract were recorded during control examinations. About 85% of our patients accept this type of prophylactics (56).

Mastectomy

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

24 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

59 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

119 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 28 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Lynch HT: Genetics and breast cancer, Van Nostrand – Reinhold, New York 1981.

2. Broca P: Traite de tumeurs. Paris, Asselin 1866.

3. Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D et al.: A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994; 266: 66-71.

4. Thompson D, Easton D: Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in BRCA1cancer risks by mutation position. Canc Epid Biomar Prev 2002; 11: 329-36.

5. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK et al.: Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer-analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 78-85.

6. Li FP, Fraumeni JFI: Soft tissue sarcomas, breast cancer and other neoplasms: a familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med 1969; 71: 747-52.

7. MalkinD, Li FP, Strong LC et al.: Germline p53 mutations In a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas and Rother neoplasms. Science 1990; 250: 1233-8.

8. Nelen MR, Padberg GW, Peeters EA et al.: Localization of the gene for Cowden disease to chromosome 10q22-23. Nat Genet 1996; 13: 114-6.

9. Hanssen AMV, Fryns JP: Cowden syndrome. J Med Genet 1995; 32: 117-9.

10. Risinger JI, Barrett JC, Watson P et al.: Molecular geneic evidence of the occurrence of breast cancer as on integral tumor in patients with the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Cancer 1996; 77: 1836-43.

11. Spigelman AD, Murday V, Phillips RKS: Cancer and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gut 1989; 30: 1588-90.

12. Cohen MM: A comprehensive and critical assessment of overgrowth and overgrowth syndromes. Adv Hum Genet 1989; 18: 181-304.

13. Shiloh Y: Ataxia telangiectasia: closer to unraveling the mystery. Eur J Hum Genet 1995; 3: 116-38.

14. Swift M, Reithauer PJ, Morrell D, Chase CL: Breast and other cancers in families with ataxia-telangiectasia. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1289-94.

15. Lynch HT, Kaplan AR, Lynch JF: Klinefelter syndrome and cancer: a family study. JAMA 1974; 229: 809-11.

16. Wooster R, Mangion J, Eeles R et al.: A germline mutation in the androgen receptor in two nrothers with breast cancer and Reifenstein syndrome. Nat Genet 1992; 2: 132-4.

17. Lindblom A, Sandelin K, Iselius L et al.: Predisposition for breast cancer in carriers of constitutional translocation 11q; 22q. Am J Hum Genet 1994; 54: 871-6.

18. Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD, Narod S et al.: Breast and ovarian cancer risks to carriers of the BRCA15382insC and 185delAG and BRCA26174delT mutations: a combined analysis of 22 population based studies. J Med Genet 2005; 42: 602-3.

19. Risinger JI, Berchuck A, Kohler MF, Boyd J: Mutations of the E-cadherin gene in human gynecologic cancers. Nat Genet 1994; 7: 98-102.

20. Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P et al.: Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2mutation. Lancet 1998; 52: 1337-9.

21. Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Byrski B et al.: Cancer risks in first degree relatives of BRCA1mutation carriers: effects of mutation and proband disease status. J Med Genet 2006; 43: 863-6.

22. Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL et al.: The Prevention and Observation of Surgical End Points Study Group. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1or BRCA2mutations. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1616-22.

23. Jakubowska A, Narod SA, Goldgar DE et al.: Breast cancer risk reduction associated with the RAD51 polymorphism among carriers of the BRCA15382insC mutation in Poland. Canc Epid Biomar Prev 2003; 12: 457-9.

24. Jakubowska A, Gronwald J, Menkiszak J et al.: The RAD51 135 G>C polymorphism modifies breast cancer and ovarian cancer risk in Polish BRCA1 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16: 270-5.

25. Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, Rosen B, Bradley L, Kwan E, Jack E, Vesprini DJ, Kuperstein G, Abrahamson JL, Fan I, Wong B, Narod SA. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1and BRCA2mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 700-10.

26. Marcus JN, Watson P, Page DL et al.: Hereditary breast cancer: pathobiology, prognosis, and BRCA1and BRCA2gene linkage. Cancer 1996; 77: 697-709.

27. Martin AM, Blackwood MA, Antin-Ozerkis D et al.: Germline mutations in BRCA1and BRCA2in breast-ovarian families from a breast cancer risk evaluation clinic. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 2247-53.

28. Menkiszak J, Jakubowska A, Gronwald J et al.: Hereditary ovarian cancer: summary of 5 years of experience. Ginekol Pol 1998; 69: 283-7.

29. Loman N, Johannsson O, Bendahl P et al.: Prognosis and clinical presentation of BRCA2-associated breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36: 1365-73.

30. Lubiński J, Górski B, Huzarski T et al.: BRCA1-positive breast cancers in young women from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 99: 71-6.

31. Lakhani SR: The pathology of familial breast cancer: Morphological aspects. Breast Cancer Res 1999; 1: 31-5.

32. Górski B, Byrski T, Huzarski T et al.: Founder mutations in the BRCA1gene in Polish families with breast-ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2000, 66: 1963-8.

33. Loman N, Johannsson O, Bendahl PO et al.: Steroid receptors in hereditary breast carcinomas associated with BRCA1or BRCA2mutations or unknown susceptibility genes. Cancer 1998; 83: 310-9.

34. Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J et al.: Localisation of a breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA 2, to chromosome 13q12-13. Science 1994; 265: 2088-90.

35. Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group. Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in a population based series of breast cancer cases. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 1301-8.

36. Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M et al.: Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1and BRCA2genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 676-89.

37. Hopper JL, Southey MC, Dite GS et al.: Australian Breast Cancer Family Study, Population-based estimate of the average age-specific cumulative risk of breast cancer for a defined set of protein-truncating mutations in BRCA1and BRCA2. Can Epid Biomar Prev 1999; 8: 741-7.

38. Warner E, Foulkes W, Goodwin P et al.: Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1and BRCA2gene mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1241-7.

39. Jakubowska A, Nej-Wołosiak K, Huzarski T et al.: BRCA2 gene mutation in familie with aggregations of breast and stomach cancers. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 888-91.

40. Jakubowska A, Scott R, Menkiszak J: A high frequency of BRCA2gene mutations in Polish families with ovarian and stomach cancer. Eur J Hum Genet 2003; 11: 955-8.

41. Kwiatkowska E, Teresiak M, Lamperska KM et al.: BRCA2germline mutations in male breast cancer patients in the Polish population. Hum Mutat 2001; 17: 73.

42. Boyd J, Sonoda Y, Federici MG et al.: Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA 2000; 283: 2260-5.

43. Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R et al.: Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 424-8.

44. McLaughlin JR, Risch HA, Lubiński J et al.: Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. Reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1or BRCA2mutations: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 26-34.

45. Narod SA, Dube MP, Klijn J, Lubiński J et al.:nontraceptives and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1and BRCA2mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1773-9.

46. Grabrick DM, Hartmann LC, Cerhan JR et al.: Risk of breast cancer with oral contraceptive use in women with a family history of breast cancer. JAMA 2000; 284: 1791-8.

47. Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Randall T et al.: Hormon replacement therapy and life expectancy after prophylactic oophorectomy in women with BRCA1/2mutations: a decision analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 1045-54.

48. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T et al.: Effect Short-Term Hormone Replacement Therapy on Breast Cancer Risk Reduction After Bilateral Prophylactic Oophorectomy in BRCA1and BRCA2Mutation Carriers: The PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 7804-10.

49. Buchet-Poyau K, Mehenni H, Radhakrishna U, Antonarakis SE: Search for the second Peutz-Jeghers syndrome locus: exclusion of the STK13, PRKCG, KLK10, and PSCD2 genes on chromosome 19 and the STK11IP gene on chromosome 2. Cytogenet Genome Res 2002; 97: 171-8.

50. Gronwald J, Byrski T, Huzarski T et al.: Influence of selected lifestyle factors on breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1mutation carriers from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 95: 105-9.

51. Narod SA: Hormonal prevention of hereditary breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001; 952: 36-43.

52. Kotsopoulos J, Lubiński J, Lynch HT et al.: The Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Age at first birth and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1and BRCA2mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 105: 221-8.

53. Gronwald J, Tung N, Foulkes W et al.: Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Tamoxifen and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1and BRCA2carriers: an update. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 2281-4.

54. Narod SA, Brunet JS, Ghadirian P et al.: Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Tamoxifen and risk of contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1and BRCA2mutation carriers: a case-control study. Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Lancet 2000; 356: 1876-81.

55. Kowalska E, Narod SA, Huzarski T et al.: Increased rates of chromosome breakage in BRCA1carriers are normalized by oral selenium supplementation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 1302-6.

56. Menkiszak J, Rzepka-Górska I, Górski B et al.: Attitudes toward preventive oophorectomy among BRCA1mutation carriers in Poland. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2004; 25: 93-5.

57. Zeigler LD, Kroll SS: Primary breast cancer after prophylactic mastectomy. Am J Clin Oncol 1991; 14: 451-3.

58. Temple WJ, Lindsay RL, Magi E: Technical considerations for prophylactic mastectomy in patients at high risk for breast cancer. Am J Surg 1991; 161: 413.

59. Warner E, Plewes DB, Shumak RS et al.: Comparison of breast magnetic resonance imaging, mammography, and ultrasound for surveillance of women at high risk for hereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3524-31.

60. Narod SA, Dube MP, Klijn J et al.: Oral Contraceptives and the Risk of Breast Cancer in BRCA1and BRCA2Mutation Carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1773-9.

61. Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T et al.: The Polish Hereditary Breast Cancer Consortium. Response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 108: 289-96.

62. Lubinski J, Korzen M, Gorski B et al.: Genetic contribution to all cancers: the first demonstration using the model of breast cancers from Poland stratified by age at diagnosis and tumour pathology. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008.

63. Cybulski C, Górski B, Huzarski T et al.: CHEK2-positive breast cancers in young Polish women. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 4832-5.

64. Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Huzarski T et al.: A deletion in CHEK2of 5,395 bp predisposes to breast cancer in Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 102: 119-22.

65. Huzarski T, Cybulski C, Domagała W et al.: Pathology of breast cancer in women with constitutional CHEK2mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005; 90: 187-189.

66. Steffen J, Nowakowska D, Niwińska A et al.: Germline mutations 657del5 of the NBS1gene contribute significantly to the incidence of breast cancer in Central Poland. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 472-5.

67. Górski B, Dębniak T, Masojć B et al.: Germline 657del5 mutation in the NBS1gene in breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2003; 106: 379-81.

68. Huzarski T, Lener M, Domagała W et al.: The 3020insC allele of NOD2predisposes to early-onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005; 89: 91-3.

69. Górski B, Narod SA, Lubiński J: A common missense variant in BRCA2predisposes to early onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2005; 7: 1023-7.

70. Menkiszak J, Gronwald J, Górski B et al.: Clinical features of familial ovarian cancer lacking mutations in BRCA1or BRCA2. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2004; 25: 99-100.

71. Hart WR: Mucinous Tumors of the Ovary: A Review. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2005; 24: 4-25.

72. Shih IeM, Kurman RJ: Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol 2004; 164: 1511-8.

73. Szymańska A: Identyfikacja genów związanych z predyspozycją do gruczolako-torbielaków śluzowych jajnika. Pr. doktorska. Pomorska Akademia Medyczna, Szczecin 2006.

74. Szymańska-Pasternak J: Identyfikacja genów związanych z predyspozycją do gruczolako-torbielaków surowiczych jajnika. Pr. doktorska. Pomorska Akademia Medyczna, Szczecin 2007.

75. Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Byrski B et al.: Cancer risks in first degree relatives of BRCA1 mutation carriers: effects of mutation and proband disease status. J Med Genet 2006; 43 (5): 424-8.

76. Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T et al.: Pathologic complete response rates in young women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010 Jan 20; 28 (3): 375-9.

77. Serrano-Fernández P, Debniak T, Górski B et al.: Synergistic interaction of variants in CHEK2 and BRCA2 on breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009 Sep; 117 (1): 161-5.