© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 12/2014, s. 814-818

*Maria Stelmachowska-Banaś, Izabella Czajka-Oraniec, Wojciech Zgliczyński

Kliniczna i hormonalna ocena pacjentów z obrazem pustego siodła tureckiego w badaniu MR

Clinical and hormonal assessment of patients with empty sella on MRI

Department of Endocrinology, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Bielański Hospital, Warszawa

Head of Department: prof. Wojciech Zgliczyński, MD, PhD

Streszczenie

Wstęp. Obraz pustego siodła jest wynikiem wgłębiania się opony pajęczej i przestrzeni podpajęczynówkowej w obręb siodła tureckiego. Obraz ten jest najczęściej przypadkowym znaleziskiem u bezobjawowych pacjentów podczas badania MR. Może być jednak związany z poważnymi zaburzeniami neurologicznymi, okulistycznymi i endokrynnymi.

Cel pracy. Celem pracy była kliniczna i hormonalna ocena pacjentów z obrazem pustego siodła w badaniu MR.

Materiał i metody. W badaniu retrospektywnym przeprowadziliśmy analizę dokumentacji medycznej pacjentów hospitalizowanych w Klinice Endokrynologii CMKP w Szpitalu Bielańskim podczas jednego roku. Wyszukano pacjentów z obrazem pustego siodła w badaniu MR i zebrano dane dotyczące wieku, płci, BMI, przyczyn choroby, czynności przysadki oraz stosowanego leczenia. Analizowano również wyniki badania MR okolicy przysadkowo-podwzgórzowej.

Wyniki. U 40 spośród 1724 (2,3%) pacjentów hospitalizowanych w Klinice uwidoczniono obraz pustego siodła w MR, w tym u 21 (52,5%) osób rozpoznano obraz pierwotnie pustego siodła (PES), natomiast u 19 (47,5%) – wtórnie puste siodło (SES). W grupie pacjentów z PES stosunek kobiet do mężczyzn wynosił 3 do 1. Ponad połowa kobiet z PES (53%) była wieloródkami. Wiek w chwili rozpoznania wynosił 47,8 ± 14,6 roku. Średnie BMI u pacjentów z PES wynosiło 27,4 kg/m2. Podczas oceny hormonalnej u 5 pacjentów (23,8%) z PES rozpoznano niedoczynność przysadki, w tym najczęściej stwierdzano niedoczynność osi gonadotropowej (19%). Hiperprolaktynemia była rzadkim zaburzeniem. U 17 pacjentów (81%) z PES stwierdzono w MR częściowo puste siodło (mniej niż połowa wysokości siodła tureckiego wypełniona płynem mózgowo-rdzeniowym), natomiast u 4 pacjentów (19%) stwierdzono całkowicie puste siodło (więcej niż połowa wysokości siodła tureckiego wypełniona płynem mózgowo-rdzeniowym).

Wnioski. Obraz pustego siodła był rzadkim rozpoznaniem u pacjentów Kliniki. Wśród pacjentów z pierwotnie pustym siodłem przeważały kobiety, wieloródki z nadwagą. U większości pacjentów rozpoznanie pustego siodła było przypadkowym rozpoznaniem, jednak u 23% prowadziło do rozpoznania niedoczynności przysadki.

Summary

Introduction. Empty sella is caused by the herniation of the subarachnoid space within the sella, which results in compression of pituitary gland. The image of empty sella may be an incidental finding on MRI in asymptomatic patients, but it can be also associated with severe neurological, ophthalmological and endocrine disorders.

Aim. The aim of the study was to analyze clinical and hormonal data of patients with empty sella on MRI.

Material and methods. We performed a retrospective review of the medical data of patients hospitalized in the Department of Endocrinology in Bielański Hospital during one year searching for those with the diagnosis of empty sella. We collected data on the age, sex, causes of empty sella, results of pituitary function and we analysed the results of MRI of pituitary-hypothalamic region.

Results. Among 1724 patients hospitalized in the Department 40 patients (2.3%) had empty sella on MRI. Twenty one (52.5%) patients were diagnosed with primary empty sella (PES) and 19 (47.5%) were diagnosed with secondary empty sella (SES). In patients with PES there were 16 (76.2%) females and 5 (23.8%) (3 to 1 ratio). More than half of PES females (53%) had a history of at least two pregnancies. The mean BMI in PES patients was 27.4 kg/m2. The mean age at diagnosis was 47.8 ± 14.6 years in the whole group. During the hormonal assessment 5 patients (23.8%) with PES were found to have some degree of anterior pituitary deficiency. The most frequent disorder (19%) was hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with symptoms of oligomenorrhoea in females and decreased sexual function in men. In seventeen patients (81%) in PES group MRI revealed partial empty sella (less than 50% of the sella filled with CSF) while in 4 patients (19%) total empty sella (more than 50% of sella filled with CSF).

Conclusions. In our study, PES was more common in middle aged, overweight multiparous women. In most cases PES was incidentally discovered by imaging study, but in some it led to diagnosis of anterior pituitary deficiency during the diagnostic evaluation.

Introduction

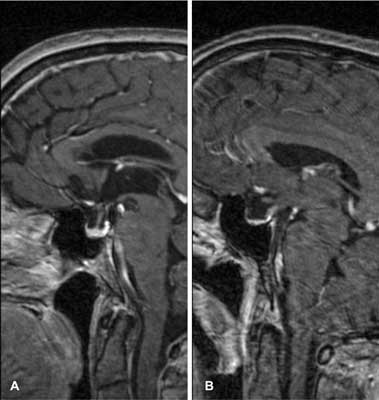

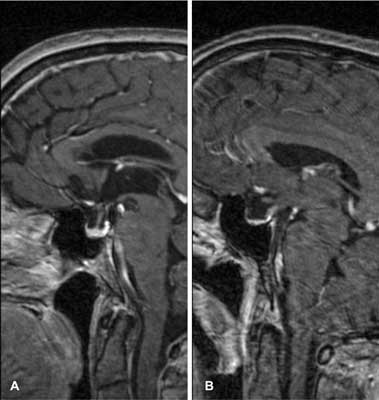

The term empty sella is referred to intrasellar herniation of suprasellar arachnoid and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of subarachnoid space, resulting in flattening of the pituitary gland (1). An anatomic defect in the sellar diaphragm has been found in up to 50% of adults and the overall incidence of an empty sella on imaging has been estimated at 12% (2, 3). Empty sella is defined as partial or total when less or more than 50% of the sella is filled with CSF respectively, with the gland thickness being < 2 mm in the latter case (fig. 1) (1). The widespread use of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has made empty sella a common incidental finding. According to data obtained from autopsies and neurological studies, the presence of empty sella ranges from 5.5 to 38% with female to male ratio of 4 to 1 (4). Two types of empty sella should be distinguished. Secondary empty sella (SES) may be caused by pituitary adenomas either undergoing spontaneous shrinkage or more often after medical treatment, surgery or radiation therapy. The image of empty sella may be also a result of a regression of an inflammatory lesions of a pituitary gland such as lymphocytic and granulomatous hypophysitis (4, 5). When no apparent cause of the herniation of subarachnoid space is present (such as surgery, radiotherapy or medical medical treatment for an intrasellar tumor) it is a primary empty sella (PES). Several etiopathogenic hypotheses have been introduced, including a congenital incomplete formation of the sellar diaphragm (1). Moreover, the empty sella has been associated with elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), posteriorly placed optic chiasm and a reduction in pituitary gland volume due to menopause, multiparity, pituitary gland infarction, obesity or dopamine agonists and somatostatin analogs treatment (6). Chronically transmitted CSF pulsations from the herniated subarachnoid space can results in bony expansion and remodeling of the sella turcica. On the other hand the empty sella is the most commonly described imaging sign in the setting of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (also known as pseudotumor cerebri) and presumably there is a correlation between the flattening of the pituitary gland and chronically elevated ICP. On MRI , the empty sella is shown by varying degrees of flatteing of the superior surface of the pituitary gland, elongated pituitary stalk and by CSF-intensity signal within the sella and is often associated with enlargement and remodeling of bony sella (7). Empty sella may be a radiological finding in asymptomatic patients, but it may be also associated with numerous disorders such as neurological, visual and endocrine.

Fig. 1. Midsagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI image shows A) partial empty sella and B) total empty sella.

Aim

The aim of the study was to retrospectively review the data of patients with empty sella on MRI hospitalized during one year in the Department of Endocrinology of The Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education in Bielański Hospital. We evaluated clinical characteristics, pituitary function and radiological features, with a detailed analysis of the magnetic resonance imaging of the pituitary-hypothalamic region results.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of patients hospitalized in the Department of Endocrinology in Bielański Hospital between September 2012 and September 2013 searching for the patients with the ICD-10 codes: D35.2 (benign neoplasm of pituitary gland) and E23. That included patients with following codes: E23.0 (hypopituitarism), E23.1 (iatrogenic hypopituitarism), E23.2 (diabetes insipidus), E23.6 (other disorders of pituitary gland). We found of 300 of such and then we searched their electronic and paper documentation to find the cases with the diagnosis of empty sella. The results of current magnetic resonance imaging of pituitary-hypothalamic region were analyzed and 40 patients had empty sella present. We estimated the pituitary height on MRI in all cases. We collected data on the age, sex, BMI, causes of empty sella and results of hormonal and ophthalmological evaluation (if available). Basal endocrine evaluation was performed in most patients: TSH, free T4, ATPO, ACTH, cortisol, LH, FSH, estradiol, testosterone (men), PRL, GH, IGF-1 (age and gender adjusted). Dynamic tests were performed to evaluate the gonadotropic axis if necessary.

Results

From September 2012 to September 2013 one thousand seven hundred twenty four patients with numerous endocrine disorders were hospitalized in the Department of Endocrinology in Bielański Hospital. Among them we found 40 patients with an empty sella on MRI which constituted 2.3% of all hospitalized patients in the Department of Endocrinology.

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

24 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

59 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

119 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 28 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. De Marinis L, Bonadonna S, Bianchi A et al.: Primary empty sella. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005 Sep; 90(9): 5471-5477.

2. Sage MR, Blumbergs PC, Fowler GW: The diaphragma sellae: its relationship to normal sellar variations in frontal radiographic projections. Radiology 1982 Dec; 145(3): 699-701.

3. Sage MR, Blumbergs PC, Mulligan BP et al.: The diaphragma sellae: its relationship to the configuration of the pituitary gland. Radiology 1982 Dec; 145(3): 703-708.

4. Foresti M, Guidali A, Susanna P: Primary empty sella. Incidence in 500 asymptomatic subjects examined with magnetic resonance. Radiol Med 1991 Jun; 81(6): 803-807.

5. Karaca Z, Tanriverdi F, Unluhizarci K et al.: Empty sella may be the final outcome in lymphocytic hypophysitis. Endocr Res 2009; 34(1-2): 10-17.

6. Guitelman M, Garcia Basavilbaso N, Vitale M et al.: Primary empty sella (PES): a review of 175 cases. Pituitary 2013 Jun; 16(2): 270-274.

7. Saindane AM, Lim PP, Aiken A et al.: Factors determining the clinical significance of an „empty” sella turcica. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013 May; 200(5): 1125-1131.

8. Sage MR, Blumbergs PC: Primary empty sella turcica: a radiological-anatomical correlation. Australas Radiol 2000 Aug; 44(3): 341-348.

9. Cannavò S, Curtò L, Venturino M et al.: Abnormalities of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in patients with primary empty sella. J Endocrinol Invest 2002 Mar; 25(3): 236-239.

10. Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Felton WL 3rd et al.: Increased intra-abdominal pressure and cardiac filling pressures in obesity-associated pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology 1997 Aug; 49(2): 507-511.

11. Sastre J, Herranz de la Morena L, Megía A et al.: Primary empty sella turcica: clinical, radiological and hormonal evaluation. Rev Clin Esp 1992 Dec; 191(9): 481-484.

12. Manetti L, Lupi I, Morselli LL et al.: Prevalence and functional significance of antipituitary antibodies in patients with autoimmune and non-autoimmune thyroid diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007 Jun; 92(6): 2176-2181.

13. Komatsu M, Kondo T, Yamauchi K et al.: Antipituitary antibodies in patients with the primary empty sella syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988 Oct; 67(4): 633-638.

14. Guinto G, del Valle R, Nishimura E et al.: Primary empty sella syndrome: the role of visual system herniation. Surg Neurol 2002 Jul; 58(1): 42-47; discussion: 47-48.

15. Brisman R, Hughes JE, Holub DA: Endocrine function in nineteen patients with empty sella syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1972 Mar; 34(3): 570-573.

16. Jordan RM, Kendall JW, Kerber CW: The primary empty sella syndrome: analysis of the clinical characteristics, radiographic features, pituitary function and cerebrospinal fluid adenohypophysial hormone concentrations. Am J Med 1977 Apr; 62(4): 569-580.

17. Gasperi M, Aimaretti G, Cecconi E et al.: Impairment of GH secretion in adults with primary empty sella. J Endocrinol Invest 2002 Apr; 25(4): 329-333.

18. Poggi M, Monti S, Lauri C et al.: Primary empty sella and GH deficiency: prevalence and clinical implications. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2012; 48(1): 91-96.