*Jan Namysł

The impact of electrostimulation and EMG-biofeedback therapy on the distribution and coordination of anal sphincter muscle tone based on the example of two randomly selected patients with fecal incontinence

Wpływ elektrostymulacji i terapii EMG-biofeedback na rozkład i koordynację napięcia mięśniowego zwieraczy odbytu na przykładzie dwóch losowo wybranych pacjentów z nietrzymaniem stolca

INNOMED – A Centre for the Treatment of Paresis in Poznań

Streszczenie

Uszkodzenia mięśni dna miednicy odpowiedzialnych za funkcje zwieraczowe oraz choroby lub urazy nerwów sterujących ich napięciem są zawsze powiązane ze zmianami funkcjonalnymi, które manifestują się w postaci dyskoordynacji jednostek ruchowych, mięśni biorących udział w skurczu. Utrudniona lub niemożliwa wymiana informacji pomiędzy ośrodkami nerwowymi regulującymi napięcie zwieraczy i proprioreceptorami powoduje, że napięcie staje się niestabilne, regulowane nieadekwatnie do potrzeb i wywołuje wiele objawów niepożądanych, bowiem napięcie bioelektryczne ma istotny wpływ na funkcje życiowe komórek mięśniowych i nerwowych. Ocena charakterystyki napięcia wyrażona w jednostkach obiektywnych, mikrovoltach, jest możliwa wyłącznie z pomocą elektromiografii. Ćwiczenia wykonywane samodzielnie oraz elektrostymulacje mogą nie przynosić oczekiwanej poprawy, jeżeli nerwowe mechanizmy dystrybucji i koordynacji napięcia mięśniowego uległy degradacji. Normalizacji czynności bioelektrycznej oraz procesom zdrowienia służą zabiegi elektrostymulacji i terapia EMG-biofeedback. Dzięki zjawiskom plastyczności układu nerwowego angażowanie świadomości w terapii EMG-biofeedback kreuje nowe obiegi neuronalne, służące normalizacji napięcia i usprawnianiu kontroli nad czynnością zwieraczy.

Summary

Damage to the pelvic floor muscles, which are responsible for sphincter functions, and diseases or injuries of the nerves that control their bioelectric activity are always associated with functional changes manifested in the form of discoordination of motor units, in muscles involved in contraction. As a result of difficult or impossible communication between neural centres that regulate sphincter tone and proprioceptors, muscle tone becomes unstable, modulated inadequately to the needs and generating many undesirable symptoms, as bioelectric voltage has a significant impact on the vital functions of muscle and nerve cells. An assessment of muscular activity expressed in objective units, i.e. microvolts, is possible only with electromyography. Self-performed exercises and electrostimulation may fail to produce the desired improvement in the case of degraded nervous mechanisms underlying the distribution and coordination of muscle activity. Electrostimulation and EMG-biofeedback therapy help normalise bioelectrical activity and thus contribute to the healing process. Plasticity of the nervous system allows for the creation of new neural networks that normalise muscle tone and improve control over sphincter activity as a result of patient’s conscious involvement in EMG-biofeedback therapy.

Introduction

Normal function of the anal sphincters depends on their anatomical structure, blood supply, innervation integrity and electrical activity generated by the nervous system to control the coordination of motor units during contraction and relaxation. Abnormal anal sphincter tone is a symptom of neuropathic changes and functional disorders, manifested in the form of incontinence or discomfort (pain, feeling of moisture and/or incomplete bowel movement, etc.). Symptoms of unstable and discoordinated activity of the pelvic floor sphincter muscles are seen in congenital nervous system anomalies (spina bifida, sacral agenesis, atresia ani, Hirschsprung disease). They can also develop secondary to acquired muscle or nerve injuries as a result of childbirth, accidents, spinal degeneration and injuries, or systemic conditions.

Dysfunction of muscle or functionally associated connective tissue (fascia, ligaments) gives rise to specific activation patterns, which are not found in healthy individuals (1). The accompanying bioelectric instability and discoordination of motor units are the result of new neural connections hastily created by the CNS due to the inability to modulate muscle tone with the already existing neural networks. Although anal sphincter manometry provides data on pressure distribution in the anal canal based the muscle response to balloon extention, this pressure depends on the activity of the nervous system and the generated muscle tone. The type and characteristics of this activity are critical for the functioning of nerve and muscle cells, since sodium and calcium ion channels in the plasma membrane responsible for transmitting electrical signals between neurons and the spread of excitation in skeletal muscles are voltage-gated. Abnormal voltage disrupts cellular functions, preventing proper functioning, regeneration and development of cells (2). The electrically charged sodium and calcium ions are crucial for muscle cell function, as the increase in sodium levels generates action potential (3), and the increase in calcium ions level activates the sliding of muscle fibers (4, 5). Professor John Byrne from the Department of Neurobiology of McGovern Medical School in Houston (USA) has also pointed out that only certain types of ions pass and carry electric charge through the cellular membrane and that genetic mutations may cause minor disturbances in the structure of ion channels, leading to pathology (6). The characteristics of the voltage generated by the nervous system is therefore important not only for the way the muscles respond to stimulation, but also for the activation of genes that support the health of muscle cells. However, ion channel mutations can also arise from epigenetic effects of abnormal voltages, as a result of nervous system disease or trauma. Lack of muscle tone caused by flaccid paralysis leads to myocytic atrophy and muscular steatosis, while chronically increased muscle tone causes fibrosis.

While it was relatively recently believed that muscle tone is a reflex response of muscle spindles to stretching independent of the nervous system (7), it is currently believed, that muscle activity is both initiated and supervised by the CNS (8). The axons of the motor cortex connect in the sacral segment of the spinal cord with the nuclei of motor neurons innervating the pelvic floor muscles, while the hypothalamus (medial part) connects with the Onuf’s nucleus (9). Neural networks formed in early childhood based on the feedback mechanism create a multi-level and highly complex mechanism of central control of defecation and gas passage. Specialised nerve centres in the brain and spinal cord register stimuli from the environment and the functional body status and, owing to the connections that enable information exchange, they construct commands for the motor neurons. The final shape of the impulses reaching the pelvic floor muscles is influenced not only by the centers of the motor cortex, but also by the pre-motor cortex (planning), the cerebellum and subcortical nuclei (coordination), and the brainstem (reflexes). An equally important role is played by the limbic system (emotions), involved in the process of learning to control the sphincter function, and the visual and auditory cortex, which provide information important for decisions about the time and place of bowel emptying. The role of the peripheral nervous system is to provide muscles with stimuli, while the central nervous system is responsible for their value, frequency, amplitude, distribution in the muscles and the post-contraction relaxation as well. Its crucial impact on the characteristics of recorded muscle activity is confirmed by the outcomes of EMG-biofeedback therapy presented in this paper.

Muscle activity can be initiated by the brain as a reflex or conscious response. While on can consciously change the sphincter tone to inhibit the defecation reflex, usually we do not control the complex mechanism of many thousands of synapses and motor units during our daily physical activity. It is controlled by groups of functionally connected neurons shaped in the course of multiple repetitions and acquired experience. Consciousness sets a goal and then registers the outcome, but decisions on the bioelectric activity control process are made by the CNS. The primary role in inhibiting the defecation reflex is played by the distal external anal sphincter (EAS); however, it is worth noting that many other pelvic floor muscles contribute to the contraction to prevent uncontrolled bowel emptying: the coccygeal muscles forming the levator plate, the transverse muscles of the perineum, the puborectalis muscle, and the internal obturator muscles, which are also innervated by the sacral plexus. It is not possible to tense any of the above-mentioned muscles in an isolated manner. It is a strong, conscious control over the contractile activity of the external urethral and anal sphincter that initiates the activity of the other pelvic floor muscles. Even partial damage to the neural network responsible for modulating the sphincter tone means that its decisions cannot be optimal. The nerve centers responsible for regulating muscle activity „do not know” what is optimal and what is not, until consciousness registers and evaluates the outcomes of their actions. The ability of the nervous system to control muscle activity arises through a feedback mechanism and is the result of experience. If the outcome of anal sphincter activity is not as expected and there is a feeling of abnormal (or different from the previous) function in the form of stool or gas incontinence, chronic constipation, disturbed perception of intestinal filling, incomplete bowel emptying, pain, etc., the malfunction of neuromuscular mechanisms is suspected. In such cases, specialist advice should be sought. Diagnostic imaging, including transrectal ultrasound, rectoscopy, colonoscopy or lumbosacral resonance, is used to confirm or exclude changes requiring surgical intervention or anti-cancer treatment. However, if diagnostic imaging fails to identify the aetiology, and the patient reports specific symptoms, an impaired voltage-controlled muscle function should be assumed. Rehabilitation is necessary as incorrect, i.e. increased, reduced, unstable and uncoordinated tone of sphincteric muscles requires adequate treatment approaches. Pharmacotherapy treatment offen fails.

Neuroregeneration-promoting nerve stimulation, with electrodes applied along neural structures, and pelvic floor muscle training using a rectal electrode in synchronisation with stimulation, are used to normalise the muscle tone (10). In addition to many other advantages, stimulation provides the muscles with stable impulses, which cannot be otherwise guaranteed by the damaged nervous system. Stimulation with parameters adjusted to the functional status and EMG-biofeedback therapy, allows for stabilisation of muscle tone both during contraction and relaxation. Stabilised muscle tone contributes to subjective feeling of improved sphincter control and can be confirmed in objective, pre- and post-treatment comparative EMG. The paper presents two case reports to show the impact of electrical stimulation and EMG-biofeedback on bioelectric activity, i.e. the distribution and coordination of anal sphincter tone and the synchronisation of motor units during contraction and post-contraction relaxation.

Two patients in whom anal sphincter tone was assessed and methods to improve the distribution and coordination of muscle activity were implemented, were randomly selected. These were two subsequent patients with sphincter problems (ID 2106 and ID 2107) who coincidentally made an appointment on the same day, 2 hours apart. Therapeutic outcomes similar to those described below, can be achieved in many other patients, regardless of age, education or occupational status. It is important that the patient is able to concentrate, draw conclusions and understand commands.

Case report 1

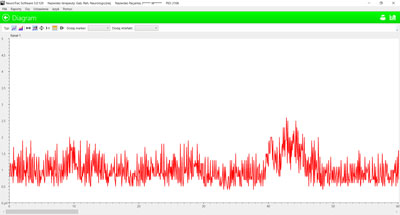

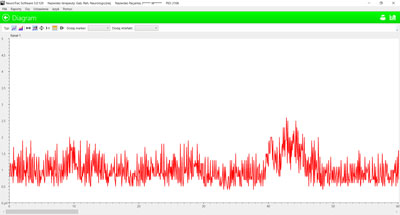

A 70-year-old professionally and socially active woman. Stool and gas incontinence developed after several months of intensive care for her husband with disability due to stroke. Incontinence probably resulted from conflicts between the overloaded spinal structures and the nervous system, disturbing nerve conduction and modifying the mechanisms that modulate muscle tone. Anal sphincter EMG and therapy were performed using a single-channel rectal electrode. EMG revealed increased resting activity of the sphincters with an average value of 1.0 μV with a high (2.2 μV) amplitude of voltage fluctuations (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Increased and unstable resting activity of the anal sphincters in a patient with stool and gas incontinence. Scale 0-5 μV

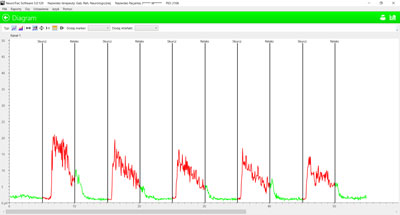

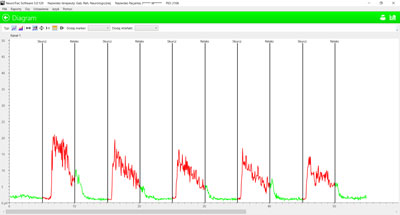

Normal resting activity in healthy individuals is about 0.5 μV, with fluctuations (amplitude) not exceeding 0.4 μV. The frequency of impulses is also much lower. The maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) test, during which the patient performs maximum contraction, showed the following results: the mean activity from all 5 contraction attempts was 9.7 μV, stability – 32.5% deviations from the mean, action during post-contraction relaxation – 1.4 μV. There was a significant decrease in the ability to maintain muscle tone during subsequent attempts to tense the muscles (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Contraction/relaxation test performed prior to ETS stimulation and EMG-biofeedback exercises. Scale 0-50 μV

The results achieved in sphincter contraction/relaxation tests by healthy individuals fluctuate during contraction around an average of 20-25 μV, post-contraction relaxation is at the level of about 0.5 μV, while the voltage deviation from the mean is stable and does not exceed 12-14%.

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

24 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

59 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

119 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 28 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Houck JR, Wilding GE, Gupta R et al.: Analysis of EMG patterns of control subjects and subjects with ACL deficiency during an unanticipated walking cut task. Gait Posture 2007; 25(4): 628-638.

2. French RJ, Zamponi GW: Voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels in nerve, muscle, and heart. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience 2005; 4(1): 58-69.

3. Rodríguez Cruz PM, Cossins J, Beeson D, Vincent A: The Neuromuscular Junction in Health and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms Governing Synaptic Formation and Homeostasis. Front Mol Neurosci 2020; 13: 610964.

4. Kuo IY, Ehrlich BE: Signaling in muscle contraction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015; 7(2): a006023.

5. Chen W, Kudryashev M: Structure of RyR1 in native membranes. EMBO Reports 2020; 21(5): e49891.

6. Byrne JH: Synaptic Transmission and the Skeletal Neuromuscular Junction. Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, McGovern Medical School 2020; https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s1/chapter04.html.

7. Prusiński A: Podstawy neurologii klinicznej. PZWL, Warszawa 1977: 36-37.

8. Sadowski B: Biologiczne mechanizmy zachowania się ludzi i zwierząt. PWN, Warszawa 2007: 272.

9. Vodušek DB: Anatomy and Neurocontrol of the Pelvic Floor. Digestion 2004; 69: 87-92.

10. Gordon T: Electrical Stimulation to Enhance Axon Regeneration After Peripheral Nerve Injuries in Animal Models and Humans. Neurotherapeutics 2016; 13(2): 295-310.

11. Namysł J, Garstka-Namysł K: Zespół ogona końskiego, rehabilitacja po porażeniach zwieraczy odbytu. Nowa Med 2022; 29(1): 20-35.

12. Masi AT, Hannon JC: Human resting muscle tone (HRMT): narrative introduction and modern concepts. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2008; 12(4): 320-332.

13. Schleip R, Naylor IL, Ursu D et al.: Passive muscle stiffness may be influenced by active contractility of intramuscular connective tissue. Med Hypotheses 2006; 66(1): 66-71.

14. Yang X, Xue P, Chen H et al.: Denervation drives skeletal muscle atrophy and induces mitochondrial dysfunction, mitophagy and apoptosis via miR-142a-5p/MFN1 axis. Theranostics 2020; 10(3): 1415-1432.

15. Salamone JD, Correa M: The Mysterious Motivational Functions of Mesolimbic Dopamine. Neuron 2012; 76(3): 470.

16. Šimić G, Tkalčić M, Vukić V et al.: Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala. Biomolecules 2021; 11(6): 823.