*Tomasz Songin

Deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum – an interdisciplinary problem

Endometrioza głęboko naciekająca przegrody odbytniczo-pochwowej ? problem interdyscyplinarny

Miracolo Clinic ? Endometriosis Treatment Centre, Warsaw

Streszczenie

Endometrioza polega na ektopowym występowaniu nabłonka gruczołowego jamy macicy, który może naciekać wszystkie narządy jamy otrzewnowej oraz w rzadszych przypadkach odleglejsze lokalizacje. Jedną z jej najcięższych postaci jest endometrioza głęboko naciekająca przegrody odbytniczo-pochwowej. W tym przypadku naciek może obejmować pochwę, macicę, odbytnicę, a także okolicę zwieraczy odbytu i mięśni dna miednicy. Taki stan będzie powodował liczne dolegliwości bólowe, w tym dyspareunie, dyschezje oraz inne objawy jelitowe, znacząco obniżając komfort życia kobiety. W diagnostyce ważną rolę pełni badanie zestawione przezpochwowe i przezodbytnicze, poprzedzone wnikliwym wywiadem. Wśród badań dodatkowych zaleca się wykonanie USG przezpochwowego, przezodbytniczego oraz MRI, których czułość i specyficzność wynosić może nawet odpowiednio 91 i 98%. Połączenie tych metod w sposób istotny zwiększa odsetek rozpoznań, skracając czas do rozpoczęcia leczenia, który obecnie wynosi średnio 7 lat. Wśród głównych metod leczniczych możemy wymienić farmakoterapię oraz leczenie operacyjne wspomagane odpowiednią dietą, fizjoterapią i psychoterapią. Włączenie leczenia hormonalnego znacząco redukuje ból, przyczyniając się do poprawy komfortu życia, przy jednoczesnych niewielkich zmianach wielkości ognisk, co wiąże się z nawrotem dolegliwości po odstawieniu leków. Metody operacyjne umożliwiają radykalną resekcję zmian, lecz mogą powodować istotne powikłania, wpływając na funkcję jelita, pęcherza moczowego, zwieraczy odbytu oraz innych narządów. W każdym przypadku wybór optymalnej metody leczenia powinien być podejmowany indywidualnie w oparciu o doświadczenie zespołu wielospecjalistycznego.

Summary

Endometriosis refers to the ectopic localization of the uterine glandular epithelium, which can infiltrate all peritoneal cavity organs as well as, though less commonly, distant locations. One of its most severe forms is deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) of the rectovaginal septum. In cases of DIE, the infiltration may involve the vagina, uterus, rectum, and the area of anal sphincters and pelvic floor muscles. The condition causes a variety of pain symptoms, including dyspareunia and dyschezia, and other intestinal complaints, significantly impairing the quality of a woman’s life. Important elements of the diagnostic work-up include obtaining the patient’s detailed history followed by transvaginal and transrectal examinations. Additional examinations recommended in patient assessment are transvaginal and transrectal ultrasonography, and MRI. The sensitivity and specificity of the methods may reach 91 and 98%, respectively. The combination of these diagnostic modalities significantly increases the rate of diagnosis, reducing the time to the start of treatment which, at present, is on average 7 years. The main management methods for DIE include pharmacotherapy and surgical treatment complemented by an appropriate diet, physiotherapy and psychotherapy. Hormone treatment markedly reduces pain, contributing to an improvement in the quality of life, and causes slight changes in the size of endometriotic lesions, which is associated with the relapse of symptoms after the discontinuation of medication. Surgical methods allow radical removal of lesions, but may cause significant complications, adversely affecting the function of the intestine, bladder, anal sphincters, and other body organs. In each case, the choice of optimum treatment should be adjusted individually to the patient based on the experience of the multidisciplinary team.

Endometriosis is defined as chronic, incurable, ectopic growth of glandular tissue which is normally found within the uterus. The etiopathogenesis of the disease has not been completely unraveled, and various theories have attributed its development to the process of metaplasia and implantation of migrating endometrial cells with accompanying immune system malfunction. In the vast majority of cases, endometriosis is limited to the reproductive organs, however, on account of the immediate proximity of crucial organs of the lesser pelvis, and the pattern of endometrial spread, the disorder must often be addressed not only by a gynecologist, but also a surgeon, proctologist and urologist. The prevalence of endometriosis among women of reproductive age is estimated at approximately 10%, so they account for a significant proportion of both outpatients and inpatients treated by physicians of these specialties. However, because of ambiguous symptoms and difficulties associated with diagnostic imaging procedures, the disease is sometimes misdiagnosed and patients are referred back-and-forth between different medical specialists. Consequently, the period until the start of appropriate treatment may be as long as 7 years. One of the most severe forms of endometriosis is deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) involving the rectovaginal septum, which is discussed in detail below.

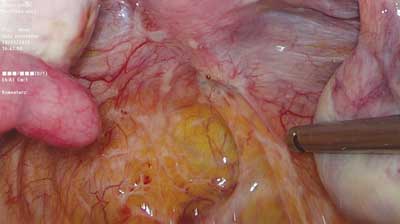

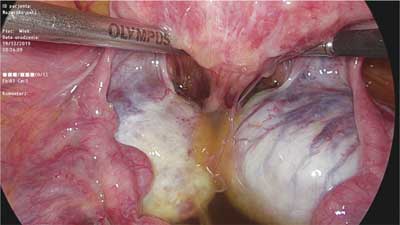

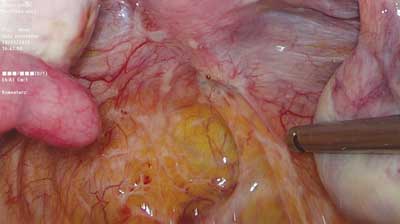

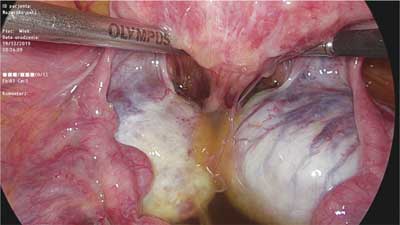

Deep infiltrating endometriosis is defined as subperitoneal invasion by endometriotic lesions exceeding 5 mm in depth. In view of differences in structure, form and function, in the 1990s endometrial lesions in the lesser pelvis were classified into three major categories: peritoneal, ovarian and deeply infiltrating ? in this case rectovaginal, with possible extension into the rectovaginal septum (RVS) (1, 2). The histopathological features of rectovaginal endometriosis which form the basis for the above division (among other factors) consist primarily of smooth muscle tissue and fibrous tissue, and to a lesser extent glandular tissue (3). This tissue composition is the underlying cause of the formation of hard, palpable nodules in this region. Differences can also be noted in the secretory activity of glandular epithelium, which ? in this location ? does not show typical changes associated with the second phase of the menstrual cycle, or the changes are incomplete. Based on these observations, the nodules were called adenomyosis of the rectovaginal septum (2, 4). Although the discussion on the origin and mechanisms underlying the development of these lesions is still ongoing, there is consensus that endometriosis involving this area is different from the peritoneal and ovarian types. The coexistence of these lesions is not necessary, so the clinical picture of endometriosis in the lesser pelvis may vary considerably. The prevalence of deep infiltrating lesions is estimated at approximately 1-2% (5). However, this value may be underestimated because of seemingly normal macroscopic features of some of the lesions (“tip of the iceberg” sign) (fig. 1) and the frequently coexisting extensive adhesion process (fig. 2), which often causes them to be “overlooked” during examinations of the peritoneal cavity.

Fig. 1. Innocuous looking endometrial lesion deeply infiltrating the right sacrouterine ligament and extending down into the rectovaginal septum and vagina (photo: Miracolo Clinic)

Fig. 2. Advanced adhesion process involving the posterior wall of the uterus, ovaries and rectum, obliterating the rectouterine pouch (photo: Miracolo Clinic)

The rectovaginal space extends from the bottom of the rectouterine pouch (also known as the pouch of Douglas) and reaches the perineal body, running between the posterior vaginal wall and the anterior rectal wall. In the sagittal plane, it can be divided into approximately 3 equal parts depending on the presence of its constituent structures including the connective tissue, nerves and blood vessels. According to a number of authors, by analogy to similar tissue found in men, an independent connective tissue structure, referred to as rectovaginal septum (RVS), is present in this area. Other authors challenge the existence of the structure, arguing that the connective tissue found in this location is a fragment of surrounding structures (rectum and vagina). The development of the tissue is sometimes attributed to high local tension (6). The rectovaginal septum consists of 2 thin elements. The upper one-third of the RVS, beginning in the peritoneal region of the rectouterine pouch, represents its thinnest part, predisposing to the development of enterocoele. Extending downwards, in the middle one-third, it has the greatest thickness and then becomes thinner again, merging into the tissue of the perineal body. The septum has no lateral boundaries, extending to the lateral vaginal wall in its anterior part, and to the rectum posteriorly. Its role and function also remain ambiguous. Since it has a relatively weak structure, especially outside the central part, the proposed function of maintaining vaginal and anal static strength is often questioned, and consequently its role is reduced to supporting vessels and nerves innervating the surrounding structures. From the point of view of endometriosis development, another important element is the presence of smooth muscle tissue within the septum. The presence of smooth muscle fibers has been confirmed immunohistochemically, though are also reports to the contrary (3, 7).

The development of endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum (RVS) may occur at one of its ends. Isolated infiltration of the septum is a rare occurrence, and usually the adjacent structures (i.e. the cervix, vagina, rectum as well as the sacrouterine ligament and the broad ligament of the uterus), are also affected. The invasion of the lower part of the septum occurs through damaged perineal and vaginal tissues. Most typically, perinatal trauma acts as a trigger, but there are also literature reports describing cases of invasion unrelated to childbirth (8). In addition to vaginal or rectal involvement, other possible findings in this area include infiltration of the anal sphincter as well as adjacent pelvic floor diaphragm muscles.

Symptoms

The presence and severity of symptoms associated with endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum depend significantly on the location, size and depth of infiltration. Occasionally, lesions in the same location may produce manifestations in some patients, while other patients remain unaffected by any symptoms. The coexistence of adenomyosis, peritoneal endometriosis as well as deep infiltrating endometriosis in another location (bladder, lateral wall of the lesser pelvis, intestine) increases the severity of pain. For the purpose of this publication, endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum can be divided into two types. Endometriosis of the lower part of the septum, in the region of anal sphincters and vaginal opening, manifests itself mainly as perineal pain in the episiotomy scar, pain during defecation and sexual intercourse (superficial dyspareunia), and the presence of a palpably tender nodule in the region of the episiotomy wound which may appear and disappear depending on the phase of the cycle. In addition to pain, symptoms include cyclic bleeding, sphincter dysfunction, and changes in stool. If endometriosis involves the upper part of the septum, the primary manifestations include deep dyspareunia, dyschezia and the presence of palpably tender nodules within the posterior vaginal vault, which may occupy its entire width, infiltrating the cervix and rectum. Depending on the degree of intestinal infiltration, symptoms of obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding may appear. They are often accompanied by generalized irritable bowel symptoms. In each of the above cases, specific symptoms may be accompanied by other complaints. The most common manifestation is pain which occurs mostly during menstruation, but it may also persist during the entire menstrual cycle or grow in severity during the ovulation phase. Other major symptoms include abnormally heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility and coexisting ovarian cysts. In cases of bladder infiltration, possible manifestations include dysuria, hematuria or overactive bladder symptoms. Occasionally, symptoms of endometriosis of the lesser pelvis can impact adjacent structures, mimicking the dysfunction of other organs, as in the case of pain in the hip joint or in the lumbosacral region. Cyclical pain in the chest and lung apices may also indicate endometriosis in the pleura or diaphragm. In addition, there is a broad spectrum of pain symptoms not caused directly by the presence of lesions involving any given organ, but induced by the circulating mediators of inflammation and pain, or by the infiltration of nervous conduction pathways.

Diagnostic work-up

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

29 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

69 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

129 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 78 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Nisolle M, Donnez J: Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril 1997; 68: 585-596.

2. Koninckx PR, Martin D: Deep endometriosis: a consequence of infiltration or retraction or possibly adenomyosis externa? Fertil Steril 1992; 58: 924-928.

3. Itoga T, Matsumoto T, Takeuchi H et al.: Fibrosis and smooth muscle metaplasia in rectovaginal endometriosis. Pathol Int 2003; 53(6): 371-375.

4. Gordts S, Koninckx P, Brosens I: Pathogenesis of deep endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2017; 108(6): 872-885.

5. Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L et al.: Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril 2012; 98(3): 564-571.

6. Dariane C, Moszkowicz D, Peschaud F: Concepts of the rectovaginal septum: implications for function and surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2016; 27(6): 839-848.

7. Nagata I, Murakami G, Suzuki D et al.: Histological features of the rectovaginal septum in elderly women and a proposal for posterior vaginal defect repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007; 18(8): 863-868.

8. Nasu K, Okamoto M, Nishida M, Narahara H: Endometriosis of the perineum. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2013; 39(5): 1095-1097.

9. Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P et al.: Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril 2011; 96: 366-373.

10. Shigesi N, Kvaskoff M, Kirtley S et al.: The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2019; 25(4): 486-503.

11. Khizroeva J, Nalli C, Bitsadze V et al.: Infertility in women with systemic autoimmune diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019: 101369.

12. Moen MH, Magnus P: The familial risk of endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1993; 72(7): 560-564.

13. Ballard KD, Seaman HE, De Vries CS, Wright JT: Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study ? part 1. Br J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 115: 1382-1391.

14. Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Kennedy SH et al.; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Women’s Health Symptom Survey Consortium: Developing symptom-based predictive models of endometriosis as a clinical screening tool: results from a multicenter study. Fertil Steril 2012; 98: 692-701.

15. Hudelist G, Ballard K, English J et al.: Transvaginal sonography vs. clinical examination in the preoperative diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37(4): 480-487.

16. Zhu L, Lang J, Wang H et al.: Presentation and management of perineal endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009; 105: 230-232.

17. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Orozco R et al.: Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in the rectosigmoid: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 47: 281.

18. Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE et al.: Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for noninvasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 37: 257.

19. Tammaa A, Fritzer N, Strunk G et al.: Learning curve for the detection of pouch of Douglas obliteration and deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum. Hum Reprod 2014; 29(6): 1199-1204.

20. Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T et al.: Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 48(3): 318-332.

21. Bazot M, Bharwani N, Huchon C et al.: European society of urogenital radiology (ESUR) guidelines: MR imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 2765-2775.

22. Fernando S, Soh PQ, Cooper M et al.: Reliability of visual diagnosis of endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013; 20: 783-789.

23. Menakaya UA, Rombauts L, Johnson NP: Diagnostic laparoscopy in pre-surgical planning for higher stage endometriosis: Is it still relevant? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 56(5): 518-522.

24. Okaro E, Condous G, Khalid A et al.: The use of ultrasound based “soft markers” for the prediction of pelvic pathology in women with chronic pelvic pain ? can we reduce the need for laparoscopy? BJOG 2006; 113: 251-256.

25. Menakaya UA, Reid S, Lu C et al.: Performance of an ultrasound based endometriosis staging system (UBESS) for predicting the level of complexity of laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016; 48(6): 786-795.

26. Catania G, Puleo C, Card? F et al.: Malignant schwannoma of the rectum: a clinical and pathological contribution. Chir Ital 2001; 53(6): 873-877.

27. Bohlok A, El Khoury M, Bormans A et al.: Schwannoma of the colon and rectum: a systematic literature review. World J Surg Oncol 2018; 16(1): 125.

28. Rodrigues BD, Alves MC, da Silva AL, Reis IG: Perianal endometriosis mimicking recurrent perianal abscess: case report and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31(7): 1385-1386.

29. Miettinen M, Furlong M, Sarlomo-Rikala M et al.: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the rectum and anus: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 144 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25(9): 1121-1133.

30. Farley J, O’Boyle JD, Heaton J, Remmenga S: Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 96(5 Pt 2): 832-834.

31. Lam MM, Corless CL, Goldblum JR et al.: Extragastrointestinal stromal tumors presenting as vulvovaginal/rectovaginal septal masses: a diagnostic pitfall. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006; 25(3): 288-292.

32. Yazbeck C, Poncelet C, Chosidow D, Madelenat P: Primary adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum: a case report. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005; 15(6): 1203-1205.

33. Ulrich U, Rhiem K, Kaminski M et al.: Parametrial and rectovaginal adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005; 15(6): 1206-1209.

34. Fujimoto T, Tanuma F, Otsuka N, Kataoka S: Laparoscopic posterior pelvic exenteration for primary adenocarcinoma of the rectovaginal septum without associated endometriosis: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol 2019; 10(1): 92-96.

35. Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C et al.: ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. Hum Reprod 2014; 29(3): 400-412.

36. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2017; 358: j4227

37. Barra F, Scala C, Maggiore ULR, Ferrero S: Long-Term Administration of Dienogest for the Treatment of Pain and Intestinal Symptoms in Patients with Rectosigmoid Endometriosis. J Clin Med 2020; 9(1).

38. Morotti M, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E et al.: Efficacy and acceptability of long?term norethindrone acetate for the treatment of rectovaginal endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 213: 4-10.

39. Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E et al.: Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2007; 62: 461-470.

40. Roman H, Rozsnayi F, Puscasiu L et al.: Complications associated with two laparoscopic procedures used in the management of rectal endometriosis. JSLS 2010; 14(2): 169-77.

41. Darwish B, Roman H: Surgical treatment of deep infiltrating rectal endometriosis: in favor of less aggressive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 215(2): 195-200.

42. Redwine DB, Koning M, Sharpe DR: Laparoscopically assisted transvaginal segmental resection of the rectosigmoid colon for endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1996; 65(1): 193-197.

43. Chapron C, Jacob S, Dubuisson JB et al.: Laparoscopically assisted vaginal management of deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectovaginal septum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001; 80(4): 349-354.

44. Chen N, Zhu L, Lang J et al.: The clinical features and management of perineal endometriosis with anal sphincter involvement: a clinical analysis of 31 cases. Hum Reprod 2012; 27(6): 1624-1627.