Izabela Pilarska1, Piotr Kwast2, Monika Jabłońska-Jesionowska2, *Lidia Zawadzka-Głos2

A complicated case of chronic stridor in an infant – a case study

Złożona przyczyna stridoru u niemowlęcia – opis przypadku

1Students’ Scientific Group of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

2Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Head of Department: Associate Professor Lidia Zawadzka-Głos, MD, PhD

Streszczenie

Stridor wdechowy jest częstym objawem spotykanym u niemowląt, stanowiącym nieraz zarówno powód do niepokoju dla rodziców, jak i wyzwanie diagnostyczne dla lekarzy. Podczas gdy samoistnie ustępująca, zazwyczaj niewymagająca leczenia laryngomalacja stanowi najczęstszą przyczynę stridoru u niemowląt, inne rozpoznania powinny zawsze być brane pod uwagę przy diagnostyce różnicowej. Przedstawiamy przypadek rocznego chłopca ze stridorem, u którego różne metody diagnostyczne sugerowały rozbieżne diagnozy. Początkowe podejrzenie laryngomalacji nie potwierdziło się w badaniu endoskopowym, które ukazało kilka równolegle występujących patologii mogących odpowiadać za objawy pacjenta. Na podstawie całokształtu obrazu klinicznego oraz dodatkowych badań radiologicznych rozpoznano naczyniaka wczesnodziecięcego krtani i włączono leczenie propranololem. Opisywany przypadek podkreśla wyzwania towarzyszące procesowi diagnostycznemu u dziecka ze stridorem.

Summary

Inspiratory stridor is a common symptom in infants that may be both a cause of worry for parents and a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. While laryngomalacia, which often does not require treatment, is the most common cause for stridor, other possible diagnoses should always be taken into consideration. We present a case of a one year old boy with stridor, in which different diagnostic procedures revealed various possible diagnoses. With a history of prematurity and neonatal intensive care treatment the initial suspicion of laryngomalacia was challenged by several parallel findings during airway endoscopy. While subsequent radiological examinations suggested different diagnoses, an infantile hemangioma of the larynx was finally diagnosed and treatment with propranolol was initiated. The described case highlights various challenges of the diagnostic process in an infant with stridor.

Introduction

Inspiratory stridor is a high-pitched sound produced during the inspiratory phase of breathing and is caused usually by an obstruction of the airways at the level of the larynx or trachea. Chronic stridor in infants can be caused by various conditions with laryngomalacia, in which narrowing of the laryngeal lumen occurs on inspiration due to softness of cartilage tissue, being the most common one. In these cases stridor usually resolves spontaneously within several weeks or months, as the cartilages of the larynx develop. Other conditions, however, must always be taken into consideration when stridor is diagnosed. Subglottic laryngeal stenosis is often encountered in children who have been intubated with an endotracheal tube during neonatal period. Congenital lesions of the larynx and trachea such as infantile hemangiomas, laryngeal cysts and laryngeal webs have to be considered. In rare cases an altered course of major blood vessels in the mediastinum also may cause stridor. A prompt and accurate diagnosis is necessary as different diagnoses mandate different forms of treatment.

Case report

We present the case of a one-year-old boy admitted to our Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology for diagnosis and treatment. The main reason for admission was unresolving stridor over the period of nine previous months. The child was born in the 29th week of gestational age by Cesarean section and was initially hospitalized for three months in the Department of Neonatology with respiratory distress syndrome. Over the course of the hospitalization the patient was intubated with an endotracheal tube twice and relied on the endotracheal tube collectively for 9 days. Stridor was first noticed by the parents shortly after discharge home from the hospital, but since the child was gaining weight properly and did not show signs of respiratory distress at home, laryngomalacia was suspected and the child was referred to the otolaryngologist only after the symptoms did not relieve after several months.

On the initial admission to the Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology the main complaints reported by the parents were restless breathing and stridor appearing in various body positions, especially while lying on the left side. The boy regurgitated rarely, choked sporadically while eating and was gaining weight properly. On admission to the Department basic otolaryngological examination did not show any pathology within the neck and pharynx. The child was qualified for endoscopy under general anesthesia. Rigid laryngo-tracheo-bronchoscopy was performed, which showed an asymmetry of the aryepiglottic folds, subglottic stenosis of less than 25% of the airway lumen, a pulsating impression on the anterior wall of the middle part of the trachea, as well as an asymmetry of the main bronchi, with a slight narrowing of the left main bronchus. Flexible videoendoscopy of the larynx was performed in the department as a complimentary method for visualizing the larynx. An oval lesion in the area of the right aryepiglottic fold, covered with pink mucosa was observed (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Lesion as initially observed in flexible endoscopy

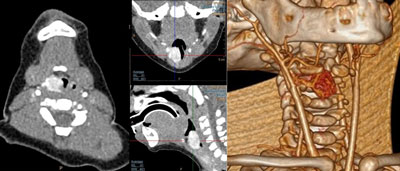

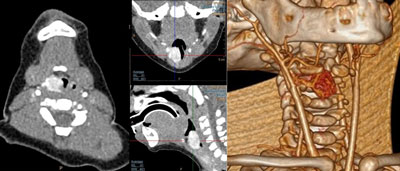

An ultrasound of the larynx was performed, which visualized the lesion found in endoscopy and was described as most likely a laryngeal cyst. Due to the uncertain nature of the lesion subsequent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. It showed an oval lesion 10 x 15 x 20 mm in size, exhibiting strong contrast enhancement, describes as a hemangioma (fig. 2). On the CT scan the diameter of the airway lumen at the height of the lesion was 2 mm. No apparent asymmetry of the main bronchi was described. Both the CT scan and subsequent echocardiography showed no great vessel abnormalities within the neck and mediastinum.

Fig. 2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the lesion

The patient was diagnosed with infantile hemangioma of the upper larynx as well as a 1st grade subglottic stenosis and treatment with propranolol was initialized. Treatment was well received with no adverse effects. During hospitalization no additional breathing difficulties were noted and the boy was discharged home.

The patient was observed during treatment on an outpatient basis. Parents reported gradual decrease of the stridor, with no adverse effects of propranolol treatment and no additional worrying symptoms. Flexible videoendoscopy was performed after six months of propranolol treatment, which revealed the hemangioma still visible (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Lesion visible in flexible endoscopy after 6 months of propranolol treatment

For additional visualisation of the leasion an MRI scan was performed, showing comparable dimensions of the hemangioma to the previous CT study (11 x 13 x 16 mm). The patient did not show any signs of respiratory distress and parents reported general improvement over the course of the treatment. The boy is currently under outpatient care, awaiting subsequent flexible endoscopy examination.

Discussion

Stridor is the most common symptom of many congenital or acquired diseases that can lead to respiratory failure (1). Stridor can be defined as noisy breathing resulting from turbulent flow through constricted airways. We can divide the stridor into inspiratory, biphasic or expiratory. This division is also linked to the location of the narrowing of the airways. Upper airway lesions more often present with inspiratory stridor while constrictions of the trachea and lower airways are more likely to produce expiratory stridor (2).

Thanks to the development of medicine, the survival rate of premature babies has increased significantly. On the other hand, however, the need for long-term hospitalization of premature infants in intensive care units increases the risk of post-intubation stenosis of the larynx or trachea. Post-intubation airway obstruction is the most common acquired cause of stridor in infants (3). However, it should not be forget that in children with a long history of hospitalization, other causes of stridor may also be present. Subglottic stenosis is usually classified according to the scale suggested by Myer and Cotton (4), in which a 1st grade stenosis of under 50% of the airway lumen is usually not considered an indication for surgical intervention, depending on the clinical presentation.

Laryngomalacia is a condition in which the larynx collapses during inspiration due to not fully developed rigidity of its’ cartilaginous structure. It is responsible for the vast majority of cases of stridor in infants and is more common in premature babies. It is rare for laryngomalacia to cause respiratory distress and failure to thrive. Stridor in laryngomalacia begins usually when the child is a few weeks old, is mostly present during activity and crying, decreases over time and resolves spontaneously (5).

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are considered the most common benign neoplasm in infancy and occur in approximately 10% of the population (6). Risk factors include female sex, prematurity, low birth weight and fair skin (6, 7). Laryngeal hemangiomas are extremely rare. Infant hemangiomas appear shortly after birth, most often as well-defined, flat and erythematous red spots. At such an early stage, the diagnosis is not obvious, but the rapid, vertical growth of the hemangioma creates a characteristic clinical picture (8). The diagnosis of hemangioma is made on the basis of a clinical history and both endoscopic and radiological imaging examination. Hemangiomas that cause a constriction of the airways during their growth usually produce gradually increasing symptoms that include stridor, dyspnea, recurrent airway infections and failure to thrive as well as acute respiratory failure.

Hemangiomas of the airways usually present as red or purple lesions and can be well differentiated from other anomalies during an endoscopic examination. In the presented case the lesion laying deeper under the mucosa did not have the most typical appearance.

Hemangiomas located in the respiratory tract require treatment. Since 2008 propranolol has been found to cause regression of hemangiomas in infants (9). Subsequent studies confirmed that in over 90% of patients, a significant reduction in hemangioma size is observed 1-2 weeks after propranolol was initiated (10, 11) and medical treatment has become the main treatment for IH (12).

In the presented case, the patient had several potential causes for stridor. His medical history pointed towards the possibility of various types of lesions in the larynx such as both laryngomalacia, laryngeal cyst, laryngeal stenosis and infantile hemangioma. One of the more important signs reported by parents proved to be the correlation between stridor and the child’s position on the left side, suggesting a lesion located to the right of the airways. The endoscopic examination revealed several signs within the airways with a potential link to the main cause of the patients’ symptoms and was not entirely consistent with radiological findings, out of which CT and ultrasound both suggested different diagnoses. Only a broad diagnostic approach provided an overview of the condition of the patient’s airways.

The treatment of infantile hemangiomas with propranolol has generally a high success rate. In the presented case symptoms relieved during treatment, with a slight improvement in radiological examination. The patient is scheduled to undergo subsequent examinations to determine the further dynamic of the lesion size.

Conclusions

We present a complex case of a child with stridor, which highlights the possible differences in outcomes of various diagnostic procedures. It is important to take various possibilities into consideration when approaching an infant with stridor on all levels of the diagnostic process. Different diagnoses will result in different treatment ranging from watchful waiting to surgical or medical intervention. Combining endoscopic and radiological imaging may help in introducing proper management and avoiding unnecessary surgical interventions.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Martins RH, Dias NH, Castilho EC et al.: Endoscopic findings in children with stridor. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006; 72(5): 649-653.

2. Jabłońska-Jesionowska M, Zawadzka-Głos L: Diagnostic evaluation of congenital respiratory stridor in children. New Med 2019; 1: 3-13.

3. Walner DL, Loewen MS, Kimura RE: Neonatal subglottic stenosis ? incidence and trends. Laryngoscope 2001; 111(1): 48-51.

4. Myer CM, O’Connor DM, Cotton RT: Proposed grading system for subglottic stenosis based on endotracheal tube sizes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994; 103 (4 Pt 1): 319-323.

5. Ayari S, Aubertin G, Girschig H et al.: Pathophysiology and diagnostic approach to laryngomalacia in infants. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2012; 129(5): 257-263.

6. Richter GT, Friedman AB: Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr 2012; 2012: 645678.

7. Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E et al.: Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. J Pediatr 2007; 150(3): 291-294.

8. Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA et al.: Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics 2008; 122(2): 360.

9. Lèautè-Labr?ze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T et al.: Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(24): 2649-2651.

10. Leboulanger N, Fayoux P, Teissier N et al.: Propranolol in the therapeutic strategy of infantile laryngotracheal hemangioma: A preliminary retrospective study of French experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 74(11): 1254-1257.

11. Buckmiller LM, Munson PD, Dyamenahalli U et al.: Propranolol for infantile hemangiomas: early experience at a tertiary vascular anomalies center. Laryngoscope 2010; 120(4): 676-681.

12. Kwast P, Jabłońska-Jesionowska M, Zawadzka-Głos L: Analysis of treatment in patients with infantile hemangioma in the Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Medical University of Warsaw. New Med 2016; 4: 107-109.