© Borgis - New Medicine 2/2003, s. 18-21

Anna Bielicka, Małgorzata Dębska, Eliza Brożek, Mieczysław Chmielik

Complications of otitis media in children – a continuing problem

Department of Paediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Head: Prof. Mieczysław Chmielik M.D.

Summary

Complications of otitis media in children are usually divided into two groups: intracranial and intratemporal. In our study we assessed the frequency of complications of otitis media in children admitted to the Department of Paediatric Otolaryngology in Warsaw between 1990 and 2003. The most frequent complications were mastoiditis (82% of children) and peripheral facial nerve paresis (10%). In two children bacterial meningitis was diagnosed, and in single cases we found labyrinthitis, zygomatic bone inflammation, and torticollis. In this study we examine some aspects of mastoiditis. This complication, in spite of widespread use of cephalosporins and semisynthetic penicillin, remains a problem, and in many cases requires surgical intervention.

INTRODUCTION

After the introduction of antimicrobial drugs in the treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children, a decreased frequency of complications of this disease was observed. In the pre-antibiotic era the frequency of intracranial complications of AOM was between 2.3-6.4 % and the resulting mortality was 76% (1). At the end of the seventies the frequency of intracranial complications had decreased to 0.04-0.15% (2), and mortality to 10- -31% (3).

Intracranial and intratemporal complications of AOM can appear as a consequence of:

– carriage of infection as a result of weakness of the osseous barrier during osteomyelitis, or the presence of a cholesteatoma,

– ascending infection as a result of thrombophlebitis,

– carriage of infection by the round window or congenital dehiscence (4).

The most frequent intratemporal complication of AOM is mastoiditis, which occurs as a result of the direct passage of purulent material to the mastoid process cells. Infection from the tympanic cavity and mastoid cells can spread laterally to the soft tissue of the postauricular region, anteriorly to the external ear canal, posteriorly towards the sigmoid sinus to the labyrinthine vestibule or apex of the petrous bone, superiorly to the middle cranial fossa, and inferiorly to the apex of the mastoid process (4).

Typical symptoms of acute mastoiditis are: reddening and oedema in the mastoid area, and smoothing of the retroauricular sulcus with anterior displacement of the pinna. In otoscopic examination signs of AOM are present, often with spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane and depression of the postero-superior wall of the external ear canal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the records of 39 patients treated for complications of otitis media between January 1990 and July 2003. Age, sex, case history, treatment, type of complication, and the results of laboratory and bacteriological investigations were analysed. Among the 39 patients were 28 boys and 11 girls. The age ranged from 2 months to 14 years, with a mean of 4.4 months.

RESULTS

Acute mastoiditis was recognised in 32 children (82%), twice more in male patients (22 boys, 10 girls). Among these, 14 were below 2 years old (44% children with mastoiditis). The complication had arisen before recognition of AOM in 14 cases. In 71% of children of less than 2 years of age, mastoiditis was the first recognised symptom of an inflammatory condition of the middle ear.

Mastoiditis was diagnosed in 30 children with acute otitis media (AOM), and in 2 children with chronic otitis media (ChOM).

Peripheral paresis of the facial nerve was recognised in 4 children (10%), 3 with AOM and 1 with ChOM.

In one girl with chronic granulomatous otitis media, labyrinthitis was diagnosed. Fistulas in the semicircular canal were found during operation.

An intracranial complication was purulent meningitis, which occurred in 2 boys, 6 months old and 2 years old.

In single cases, as coexisting diseases, were zygomatitis, torticollis, pericarditis, bilateral pneumonia with pleural effusion, and agranulocytosis.

In 20 children (62.5%) with mastoiditis there was a bacteriological culture of pus obtained from the mastoid cavity during operation, from the external ear canal after spontaneous perforation, or after paracentesis. In 47% of cases the bacteriological cultures were positive. The most frequently isolated were Streptococcus pneumoniae (5 cases), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 cases), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (3 cases). In single cases Escherichia coli, Hemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus coagulase – negative, and Staphylococcus aureus were found. In one child with meningitis, in a microscopic preparation of cerebro-spinal fluid Neisseria meningitis was found, but bacteriological culture of pus from the ear canal was negative.

Leukocytosis in patients ranged from 7.5 to 35 thousand per microlitre, mean 16.5. In one patient (6-month old boy with meningitis and mastoiditis) an agranulocytosis with 2% of granulocytes in blood smear was present. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate ranged from 5 to 165 mm/hr, mean 64mm/hr.

Fever above 38°C was present in 27 children (69%). Otopyorrhea on admission was found in 14 cases (36%).

In all children with mastoiditis reddening and oedema in the mastoid area, smoothing of the retroauricular sulcus, and different degrees of anterior displacement of the pinna were present.

A temporal bone x-ray was made in 13 patients, and computed tomography used in 5 others.

Radiological examination of 3 children revealed bone destruction and in two of these chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma was recognised, whereas one had chronic otitis media with granulation.

All children after admission were treated with intravenous antibiotics. In 29 children (74%) surgical treatment was also applied: paracentesis (10), antromastoidectomy (7), antrotomy (4), paracentesis and antrotomy (4), paracentesis with antromastoidectomy (3), and one child had a radical conservative operation. In the remaining 10 children only conservative treatment was applied.

DISCUSSION

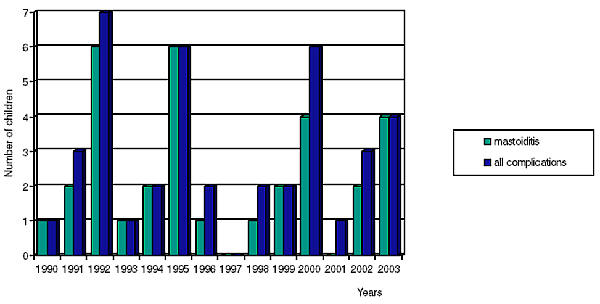

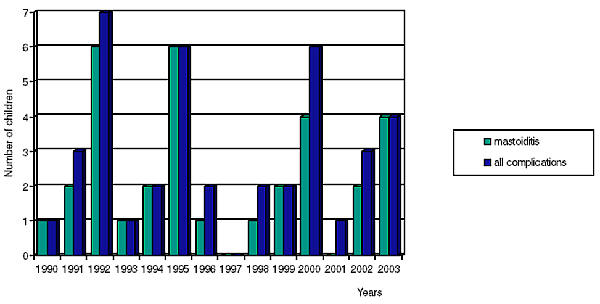

Many authors emphasise that after reducing the number of complications of acute otitis media due to the widespread use of antibiotics in the treatment of AOM, an increase in the number of children referred with acute mastoiditis has been observed since 1989 (5, 6, 7). Our studies span the period since 1990, and we have not been able to verify this tendency. The number of children with acute mastoiditis in our basic records on all complications of otitis media in particular years is schown in fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Number of children with acute mastoiditis in our records of all complications of otitis media in particular years.

In 1959 Palva (8) reported that in 0.4% of children AOM is complicated by mastoiditis, but in 1980 this incidence was only 0.004% (9). Nowadays investigators estimate that mastoiditis may occur in about 0.002-0.004% of children with AOM (10), and the number of children with this complication since 1989 has risen (6, 10). The explanation for this situation may include the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria as a result of the common use of broad spectrum antibiotics as first-line agents in the treatment of otitis media, and the use of suboptimal doses of antibiotic or insufficient duration of therapy (5).

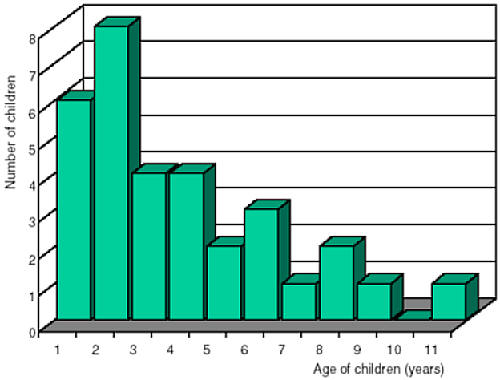

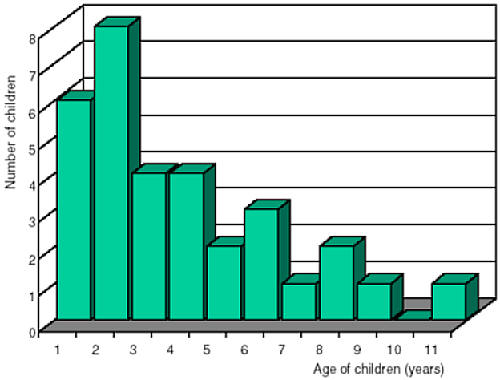

Nowadays antritis and mastoiditis appear mainly in infants or small children. In the laryngological literature, many authors underline that in the preantibiotic era this complication was a disorder of older children and adults (5, 10). In our material children below 2 years of age constitute 44% of all children with acute mastoiditis (fig. 2). Other investigators show a similar percentage, quoted as 40% by Spratley (6), and 38% by Ghaffar (5).

Fig. 2. Number of children with acute mastoiditis by age.

Acute mastoiditis without a previous episode of recognised acute otitis media was diagnosed in 44% of children. Other authors report that about half of the cases of acute mastoiditis have a similar course (6, 11, 12). This may be connected with an infrequent recognition of AOM in infants at the onset of the disease because of the non – specific symptoms of AOM (anxiety, vomiting, diarrhoea, or aversion to food), especially in small children with immunological immaturity (12).

Lentz, in multicentre studies, underlines a higher risk of mastoiditis in patients with recurrent otitis media, and the more serious course of this disease in patients with spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane (11). Our investigations do not confirm this observation.

The distribution of micro-organisms isolated in acute mastoiditis differs from that most often found to cause AOM. In our study the following were most commonly isolated: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus epidermidis, a positive bacteria culture being obtained in 47% of cases. Ghaffar (5) and Luntz (11) most often isolated: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and obtained positive cultures respectively in 60.5% and in 80% of patients.

A diagnosis of acute mastoiditis is based mainly on clinical examination. X-ray films of temporal bones according to Schuller´s projection may have limited value in the recognition of acute mastoiditis, particularly in infants, but many authors underline the importance of computed tomography in establishing a diagnosis of acute mastoiditis, estimation of intratemporal and intracranial complications, and in making a decision about surgical treatment (6, 10).

The treatment of acute mastoiditis has changed since the introduction of antibiotics. This disease was classically considered to be a surgical disease, requiring mastoidectomy irrespective of the patient´s age (13). Nowadays proper intravenous therapy and paracentesis (if early avoiding a spontaneous perforation) is sufficient in many cases. In cases of mastoiditis complicated by subperiosteal abscess a tympanostomy tube insertion, intravenous antibiotics, and postauricular incision and drainage of the abscess are recommended (13). Linder recommends surgical treatment in all patients with subperiosteal abscess, and in patients in whom acute mastoiditis occurs in spite of early antibiotic therapy (7). Linder recommends conservative treatment alone for patients with mastoiditis without previous antibiotic therapy, and without other complications. In our material the percentage of patients treated with antrotomy or antromastoidectomy was 56%, in Linder 76% (7), and in Luntz 25.6% (11).

In pharmacological therapy of intratemporal complications of AOM in our Department since 1996 we normally use cefuroksym and klindamycin. In such cases Linder most often gives amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (7), Tarantino uses ceftazidim with netylmycin (10).

CONCLUSIONS

Acute mastoiditis remains a very important problem in paediatric laryngology. Most cases of acute mastoiditis occur in infants and small children, and often in very young children this disease is the first recognised sign of ear disease. In older children an occurrence of acute mastoiditis may arouse suspicions of cholesteatoma. In the treatment of acute mastoiditis without subperiosteal abscess and other complications, antibiotic therapy and paracentesis is usually sufficient, but in many cases changes are so advanced that surgical treatment is necessary on admission to hospital.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Kafka M.M.: Mortality of mastoiditis and cerebral complications with review of 3225 cases of mastoiditis with complications. Laryngoscope 1935; 45:790-822. 2. Slattery W.H., House JW.: Complications of otitis media. In: Lawani A.K., Grundfast K.M., eds: Pediatric otology and neurotology. New York, Lippincott-Raven, 1998: 251-63. 3. Gower D., Mc Guirt W.F.: Intracranial complications of acute and chronic infectious ear disease: a problem still with us. Laryngoscope. 1983 Aug; 93(8): 1028-33. 4. Wetmore R.F.: Complications of otitis media. Pediatric Annals 2000; 29:637-46. 5. Ghaffar F.A. et al.: Acute mastoiditis in children: a seventeen-year experience in Dallas, Texas. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001 Apr; 20(4):376-80. 6. Spratley J. et al.: Acute mastoiditis in children: review of the current status. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Nov 30; 56(1):33-40. 7. Linder T.E. et al.: Prevention of acute mastoiditis: fact or fiction? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Dec 1; 56(2):129-34. 8. Palva T., Pulkkinen K.: Mastoiditis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 78(1959): 573-88. 9. Plava T. et al.: Acute and latent mastoiditis in children. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1985 Feb; 99(2):127-36. 10. Tarantino V. et al.: Acute mastoiditis: a 10 year retrospective study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 66(2002):143-48. 11. Luntz M. et al.: Acute mastoiditis – the antibiotic era: a multicentre study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001 Jan; 57(1):1-9. 12. Dhooge I.J. et al.: Intratemporal and intracranial complications of acute suppurative otitis media in children: renewed interest. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999 Oct 5; 49 Suppl 1:S109-14. 13. Bauer P.W. et al.: Mastoid subperiosteal abscess management in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002 May 15; 63(3):185-8.