© Borgis - New Medicine 2/2003, s. 26-29

Małgorzata Dębska, Eliza Brożek, Anna Bielicka, Mieczysław Chmielik

Complications of sinusitis in children hospitalised between 1994 and 2002

Department of Paediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland

Head: Prof. Mieczysław Chmielik M.D.

Summary

Acute sinusitis is a quite commonly occurring disease, although complications have rarely been reported in recent years. Children admitted to the Paediatric Otolaryngology Department of the Medical University in Warsaw between 1994-2002 due to a complicated course of sinusitis were analyzed. The management required, the course of treatment, and length of stay were taken into consideration. The most frequently – occurring complications among orbital, bone and intracranial complications were inflammatory oedema of the eyelids.

INTRODUCTION

Sinusitis and its complications in children are quite frequently discussed. It is very important to follow information in this field in order to apply the most efficient management. The occurrence of complicated sinusitis depends on the anatomical structure of the nasal cavities and sinuses, and but also on the immunological processes responsible for both the local and general immunity of the developing system. Knowledge of sinus development in a child is particularly important in appropriate interpretation of radiological examination, thus facilitating a differential diagnosis.

THE DEVELOPMENT AND ANATOMICAL RELATIONS OF THE PARANASAL SINUSES

Paranasal sinus growth occurs due to the pneumatization process i.e. the enlargement of mucosal recesses in the facial skeleton and a bone resorption process. Two stages of pneumatization are distinguished, primary involving the maxillary sinuses, anterior and posterior ethmoid cells and frontal sinus, and secondary, covering all the sinuses including the sphenoid sinus (1).

Of particular importance in the development of sinuses are the anterior ethmoid cells, for they appear first viz. between the 2nd and 3rd month of foetal life and at birth their dimensions are 5x2x3 mm (2). They reach their final shape around the 12th year of age. They drain into the nasal cavities in the upper part of the middle meatus through the ethmoidal infundibulum. Next, the posterior ethmoid cells appear about the 6th month of foetal life, and in a newborn their size is approximately 5x4x2 mm (2). They drain into the superior meatus. Their growth ends simultaneously with the anterior ethmoid cells. It is clinically important that the ethmoid cells are better developed in infancy than other sinuses, and that they lie close to the orbital tissues. The orbital wall is thinnest in the area of the lamina papyracea. This means that ethmoiditis in newborns and infants always implies the possibility of an inflammatory spread in the orbital tissues. Sinusitis expansion through continuity may occur due to the existence of bony dehiscences in the wall of the orbit, most commonly existing in the area of the above-mentioned lamina papyracea.

The 3rd month of foetal life brings the onset of development of the maxillary sinuses. At delivery, their size is 7x3x5mm, bilaterally. These narrow fissures, lying on the sides of the nasal cavities and reaching the infraorbital canal, are filled with tooth buds and cancellous bone. The gradual growth of the maxillary sinuses depends on the process of teeth eruption. The beginning of secondary dentition (about the 7th year of age) allows the maxillary sinus to enlarge effectively. It reaches its final size at age twenty. In the beginning, it communicates with the nasal cavity through an aperture 4mm long and 1mm wide, finally forming the ethmoidal infundibulum. Until the 6th-8th year of age, the bottom of the sinuses lies above the bottom of the nasal cavities, which is important in clinical practice when performing a sinus puncture (1).

The frontal sinus either does not exist in a newborn, or only forms a minute frontal recess, which does not present any particular growth features until the 6th year. The chance of ethmoiditis spreading towards the frontal sinus and on towards the brain is small, due to sufficiently thick bony structures. The risk of acquiring meningitis this way is very rare. In the literature we can find a few cases of frontal sinusitis complicated with subperiosteal abscess formation in the orbital wall. Their occurrence was probably connected with the existence of bony dehiscence in other places than the lamina papyracea (3). The frontal sinus reaches its final size and shape at age twenty.

Similarly, the sphenoid sinus shows a late onset of development. From originally being a small recess, it starts to have a lumen at the age of 4, and it grows until the 15th or 16th year. Some paricular structures lie close to the sinus; viz: cranial nerves II-IV, the internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, spheno-palatine nerve and ganglion, pituitary gland and dura mater. Cadaver studies show that the bone between the sinus and the optic nerve is less than 0.5 mm thick and in 4 % of the study group there was bony dehiscence (4). Such anatomy favours the complications, especially the loss of vision.

Paranasal sinus hypoplasia may occur in diseases such as: pituitary microsomia, Down´s syndrome, hemifacial hypoplasia but also may exist as an isolated form.

It is worth mentioning the vascular system, especially the veins joining the maxillary sinuses, the frontal sinus and the ethmoid cells with the orbit and middle cranial fossa. These veins are important for their lack of valves, which allows an easy way of communication between the above-mentioned structures.

COMPLICATIONS OF SINUSITIS

Complications of sinusitis can be divided into orbital, bone (osteomyelitis), and intracranial complications. The classification in the first group has been changing since 1937 when Hubert specified five groups relative to the intensity and scope of inflammatory changes:

1. Oedematous eyelids with or without orbital tissue oedema,

2. Subperiosteal abscess with eyelid oedema and purulent excudate,

3. Orbital abscess,

4. Orbital cellulitis and phlebitis,

5. Thrombophlebitis of the cavernous sinus.

In course of time the above classification has been modified. It is worth mentioning that each category is not a separate disease, but together they present a certain continuity, giving the idea of an advancing inflammatory process. At the moment the greatest interest is focused on Chandler´s classification (1970) (table 1).

Table 1. Complications of the sinuses after Chandler.

| Group 1 | Eyelid oedema in the preseptal area without the loss of either eyeball motility or visual acuity |

| Group 2 | Orbital cellulitis without subperiosteal abscess formation |

| Group 3 | Orbital cellulitis with a subperiosteal abscess formed between the periosteum and the bone forming the orbital cavity |

| Group 4 | Orbital cellulitis associated with an abscess in the orbital fat - proptosistranslocating the eyelid forwards, severe limitation of mobility and loss ofvision due to optic neuropathy |

| Group 5 | Cavernous thrombophlebitis - phlebitis in the orbital cavity, involving the cavernous sinus, and spreading on the opposite side through the basilar venous plexus resulting in bilateral changes |

The orbital complications described usually occur unilaterally, although the literature has provided us with a case of bilateral occurrence without affecting the cavernous and basilar venous plexus (6). A subperiosteal abscess in a child´s orbit has also been described in the superolateral part, as a complication of frontal sinusitis (3).

Complicated sinusitis in children also covers maxillary osteomyelitis and frontal osteomyelitis (with Pott´s puffy tumour). The spongy substance in the frontal bone and in the upper jaw of younger children contains vessels called Brechet veins. Due to their structure, they favour thrombus formation close to the wall of the vessel, thus leading to osteomyelitis. Maxillary osteomyelitis is characteristic of the presence of inflammatory infiltration in the buccal region, which may spread towards the palate and alveolar processes and lead to the formation of an alveolar fistula. An inflammatory condition involving the zygomatic process may spread in the supratemporal or pterygopalatine fossa. Inflammation involving the anterior wall of the frontal sinus may produce a subperiosteal abscess, continuing to the soft tosues of the forehead, with skin oedema, i.e. Pott´s puffy tumour.

Intracranial complications include: meningitis, epidural and subdural abscesses, and brain abscess. This group of complications occurs relatively rarely in children, unless disorders exist which predispose to a complicated course of disease, such as immunodeficiency disorders, or neoplasmatic processes. The history may reveal head trauma, especially important when accompanied by a fracture in the facial skeleton.

The diagnostic process involves radiological examination with computed tomography. A CT scan allows precise evaluation of a patient and facilitates the choise of further management. Computed tomography also yields indications for surgical treatment.

Methods of laryngological management in complicated sinusitis begin with a properly adjusted pharmacotherapy, involving intravenous antibiotics at their highest dosage, and mucosal decongestants. Surgical treatment is indicated where:

1. there is an abscess on the CT scan

2. symptoms of orbital compression exist i.e. worsening visual acuity and eye movements

3. conservative treatment does not start recovery within 48 hours from the beginning of aggressive therapy.

Basic surgical treatment includes: maxillary sinus puncture, ethmoidectomy, and frontal sinus puncture (Beck puncture). Since 1985, endoscopic devices have been used as an alternative to surgical treatment. The major advantage is a less invasive character, with comparable efficiency in the removal of necrotic tissues and drainage of the purulent exudate.

COMPLICATIONS OF SINUSITIS IN THE DEPARTMENTAL RECORDS

From 1994 to 2002, 85 patients were admitted to the Paediatric Otolaryngology Department of the Medical University of Warsaw, due to acute complicated sinusitis. We analysed 57 cases with full documentation. The study group consisted of 37 males and 20 females. The age ranged from 3 months to 16 years, mean 4.3 years. The frequency of complications is shown in table 2.

Table 2. Frequency of complications.

| Complications of sinusitis | Number of children (%) |

| Orbital complications | 52 (93%) |

| Bone complications | Maxillary osteomyelitis | 2 (2.8%) |

| Frontal osteomyelitis | 2 (2.8%) |

| Intracranial complications | Subdural abscess | 1 (1.4%) |

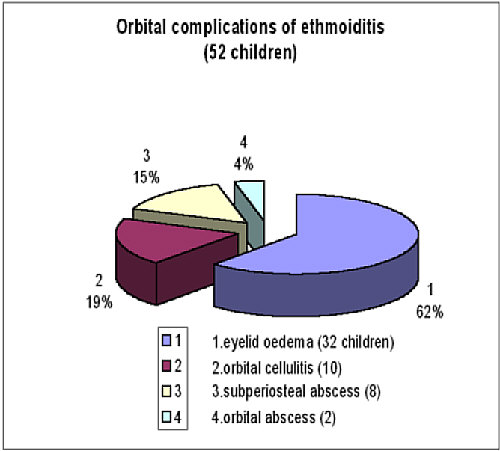

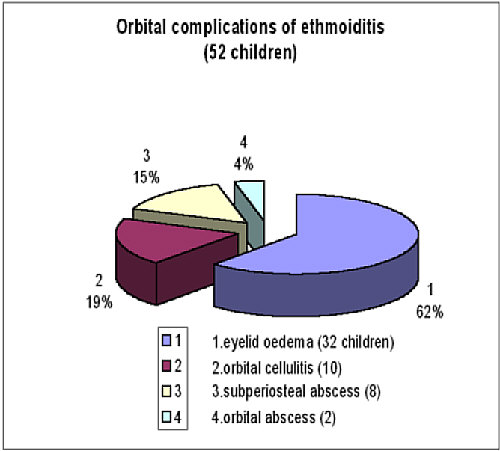

Fig. 1. Orbital complications of ethmoiditis (52 children).

Ethmoiditis with orbital complications was observed in 52 children (93%), 32 with eyelid oedema and 10 with orbital cellulitis. Eight had surgically – confirmed subperiosteal abscess, and in two cases the abscess was in the orbit. Other complications were rare, i.e. maxillary osteomyelitis was recognised in 2 patients (2.8%) and frontal osteomyelitis in 2 (2.8%). One child (1.4%) with sinusitis was admitted after neurosurgical treatment of the subdural abscesses. Two children with sinusitis were suspected of meningitis due to the occurrence of opistotonus, but cerebro-spinal fluid examination showed negative.

In the first group, the most prominent symptom was unilateral oedema and flare of the eyelids, worsening in a few hours or days, and accompanied by fever ranging from 38 to 40°C. Bilateral oedema was rarely observed. The histories often revealed an antecedent infection, either treated conservatively with antibiotics or not. Sometimes headaches and vomiting were observed. Laboratory tests showed an increased level of white blood cells (10.000 to 30.000/mm3), with granulocytes elevated in the blood smear. Erythrocyte sedimentation was either normal or elevated, ranging from 5 to 108 mm/hr.

X-rays of the sinuses performed in 39 out of 52 cases of sinusitis with orbital complications (75%) revealed apneumatic and opacified maxillary sinuses or ethmoid cells. As newer and more precise methods of imaging became available, X-rays were gradually replaced by computed tomography (29 cases, 50.1%). The accuracy of the radiological picture after surgical treatment was confirmed in 68.8%. Among the incorrect results, instead of the supposed orbital cellulitis, surgery revealed subperiosteal abscess (25%). In one case subperiosteal abscess was diagnosed, but orbital cellulitis was found (6.2%).

Conservative treatment of complicated sinusitis usually involved dual therapy, with antibiotics such as 2nd generation cephalosporins (cefuroxime) combined with lincozamids (lincomycin or clindamycin). The mean length of intravenous antibiotic therapy was 8.5 days ranging from 3 to 16 days. Subsequent oral administration was continued until the 14th day of treatment.

Surgical management was applied in 29 cases (55.8%). Seventeen children had either left-side or right-side ethmoidectomy, performed with a maxillary puncture in 10 cases. One frontal sinus puncture was made, accompanied by maxillary punctures and ethmoidectomy. In 11 cases unilateral or bilateral maxillary puncture was the sole surgical method chosen. In total, 21 maxillary punctures were performed. The mean hospitalisation time was 10.5 days. The purulent exudate obtained from the sinuses was cultured. In 9 cases the culture was positive. The species found in the maxillary sinus were Str. pyogenes (2), Moraxella sp.(1), and Haemophilus influenzae (1); from the ethmoid cells: Staphylococcus aureus (2), Staphylococcus epidermidis (1), and Staphylococcus hominis (1); from the frontal sinus: Porphyromonas asaccharolitica (1), and Peptostreptococcus spp (1). In one of these cases Acinetobacter lwoffi was cultured from a blood sample.

Right maxillary osteomyelitis occurred in 2 children aged 6 months and 10 years with buccal oedema, producing facial asymmetry. In one of these cases the symptoms initially suggested ethmoiditis with orbital complications. The younger patient in the first month of life suffered staphylococcal sepsis, with a maxillary abscess on the right side and fistula formation in the alveolar process and hard palate with subsequent self-drainage. The treatment included a lincozamid (clindamycin) followed by 3rd generation cephalosporin. In the older child lincomycin was administered with amoxicillin and clavulonic acid. Conservative treatment was applied between 4 to 6 weeks.

Frontal osteomyelitis occurred in a 10-year-old, and in a 16-year old girl. The histories of these children revealed a few days of prodromal upper respiratory airway infection with oedema formation and local pain in the projection of the frontal sinus, with temperatures over 39°C. They complained of severe headaches. The laboratory findings confirmed the inflammatory process. Sinus X- -rays made in two children showed complete opacity of the maxillary sinuses, ethmoid cells, and partial opacity of the frontal sinus. The management included exudate evacuation through frontal sinus puncture performed with a maxillary sinus puncture. Culture resulted in the growth of Streptococcus pyogenes group A.

One child admitted to the hospital had a history of upper respiratory tract infection with headaches, vomiting, high fever and gradual development of hemiparesis. A few months earlier the boy underwent an episode of head trauma. No fracture was noticed in the bones of the skull. However, coincidence of sinusitis and subdural abscesses was noted. Initially the child was treated conservatively in the paediatric department. When hemiparesis occurred he was moved to the neurosurgical department, where he underwent abscess drainage due to his worsening condition. Finally, he was moved to the otolaryngology department in order to provide further treatment. The management included frontal sinus drainage and, after 3 weeks, plastic surgery of the lateral nasal wall with frontal sinuscopy. The frontal drainage lasted 30 days, until the sinus content culture became negative. The antibiotic treatment included meronem, metronidazole and flukonazole administered intravenously for 60 days, and locally meronem, and metronidazole with decongestants through catheters for 30 days. The patient was discharged in good condition after 37 days of stay in the Paediatric Otolaryngology Department.

Summing up, it is important to underline that a simple infection of the upper respiratory tract may, if inadequately treated or disregarded, lead to severe complications. This implies a careful evaluation of every patient, especially in his/her childhood, when the immunological barriers are not fully developed. Particular attention should be paid to specific history features, viz. head trauma or previous episodes of the same disease.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Chmielik M.: Otolaryngologia Dziecięca. Warszawa PZWL 2000. 2. Krzeski A., Janczewski G.: Choroby nosa i zatok przynosowych. U&P 2003. 3. Pond F., Berkowitz R.G.: Superolateral subperiosteal orbital abscess complicating sinusitis in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999; 48(3):255-258. 4. Postma G.N. et al.: Reversible blindness secondary to acute sphenoid sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 112(6):742- -46. 5. Lusk RP.: Pediatric Sinusitis. Raven Press, New York 1992. 6. Mitchell R. et al.: Bilateral orbital complications of pediatric rhinosinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 128(8):971-974. 7. Souliere Jr.C.R. et al.: Selective non-surgical management of subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: computerized tomography and clinical course as indication for surgical drainage. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1990; 19(2):109-119. 8. Jones N.S. et al.: The intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis: can they be prevented? Laryngoscope 2002; 112(1):59-63. 9. Younis R.T. et al.: The role of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with sinusitis with complications. Laryngoscope 2002; 112(2):224-229. 10. Mortimore S., Wormald P.J.: Management of acute complicated sinusitis: A 5- -year review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 121(5):639-42.