© Borgis - New Medicine 2/2009, s. 35-39

*Eryk Chrapowicki1, Bogdan Ciszek2, 3

Anatomical review of the human fetal superior hypogastric plexus

1Department of Surgery, Gostyńska Memorial Hospital, Warsaw

2Department of Anatomy, Centre of Biostructure Research, Warsaw Medical University

3Department of Neurosurgery, Bogdanowicz Memorial Hospital for Children, Warsaw

Summary

Aim of the study.The aim of the study was to describe the morphology and topography of the human fetal superior hypogastric plexus (SHP). It is an important structure of the human autonomic nervous system. Its innervation range emphasizes its important role in several critical reflexes of the urinary and genital organs; therefore understanding of morphology and topography of the SHP is very important in surgical procedures performed in the pelvic region.

Material and methods. The study was carried out on 25 human fetuses of both sexes, aged 16-28 weeks. They were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution, and subsequently blood vessels were injected with colour latex. Dissections of the fetuses were carried out under a surgical microscope. In each case, the SHP was dissected followed by establishment of its trunk and margins. The upper and lower margins of the plexus were defined. The length, width, and distances between margins of the plexus and inferior mesenteric artery and promontory were measured. The statistical analysis of the measurement results based on Pearson´s correlation was performed.

Results. The plexus trunk, upper and lower margins may be easily established. Two upper branches and two hypogastric nerves were observed in each case. The width of the plexus and its inferior margin marked by the level of its bifurcation were constant. The most variable feature of the plexus was its length.

Conclusions. We established that the superior hypogastric plexus is an easily identifiable and preparable structure. Its form and margins may be rather distinctly separated.

Introduction

Knowledge of anatomy of the abdominal and pelvic part of the autonomic human nervous system plays a more and more important role along with progress in surgery of the distal part of the alimentary tract and genitourinary system.

The superior hypogastric plexus (SHP) forms the lower part of the intermesenteric plexus. It is located in front of the aortic bifurcation, fifth lumbar vertebra, and sacral promontory. The above-mentioned plexus typically originates beneath the beginning of an inferior mesenteric artery; however, the distance between the main part of the plexus and the artery may vary (7).

In front of the sacral promontory, the plexus typically divides into two hypogastric nerves that descend curving laterally and backwards into the pelvic cavity. They are located medially to the ipsilateral common iliac vessels. Delicate interlacing fibres often bridge the space between those two nerves (3).

The hypogastric nerves terminate in corresponding pelvic plexuses, and contribute branches to the distal colon, ureter, testis or ovary. The range of their innervations presents evidence of the important role they play in many visceral reflexes of the genital and urinary organs.

The SHP contains sympathetic postganglionic fibres from the intermesenteric plexus, and parasympathetic fibres from the splanchnic pelvic nerves which enter it at the level of hypogastric nerves (1, 2, 6, 8).

Recent development of rectal laparoscopic surgery caused increased interest in the anatomy of the superior hypogastric plexus, and understanding it better would help to reduce the number of serious complications related to plexus surgical injury. The most common ones include urine incontinence and impotence (5, 9, 10, 11).

So far only a few papers have poorly described fetal development of SHP (4, 7, 13).

Therefore the authors of this study present their investigation on morphology and topography of the superior hypogastric plexus in the human fetus.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to describe the morphology and topography of the human fetal superior hypogastric plexus.

materials and Methods

The study was carried out on 25 human fetuses of both sexes (14 male and 11 female), aged 16-28 weeks, which were destined for scientific research. They were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution for five weeks, and subsequently blood vessels were injected with colour latex. Dissections and examinations of the fetuses were carried out under a surgical microscope with microsurgical instruments. In each case, the superior hypogastric plexus was dissected followed by establishment of its trunk and margins. The upper margin of the plexus was defined as the point where two upper branches from the intermesenteric plexus connect. The lower margin was established as the place where the plexus bifurcates into hypogastric nerves.

The following parameters were measured:

1) Length and width of the plexus. The first parameter was defined as the distance between the point of connection of the upper branches and the bifurcation and the second one as SHP width measured at its widest point;

2) Distance between upper plexus margin and the inferior mesenteric artery;

3) Distance between lower plexus margin and promontory;

4) Shift of the plexus to the left from the mid-sagittal body plane.

We performed a statistical analysis of the measurement results based on Pearson´s correlation.

Results

In all analyzed specimens the SHP was composed of a central, well defined part, called the trunk. It consisted of nerve fibres and compact connective tissue.

It was located in the plexus midline. Upwards the trunk communicated by two branches (upper right branch = URB and upper left branch = ULB) with the intermesenteric plexus. Downwards the body divided into the two hypogastric nerves (left hypogastric nerve = LHN and right hypogastric nerve = RHN). The central body´s shape was variable. It was typically elongated and trapezoidal (22/25 cases) with the base directing downwards. The figures below present the structure of the plexus.

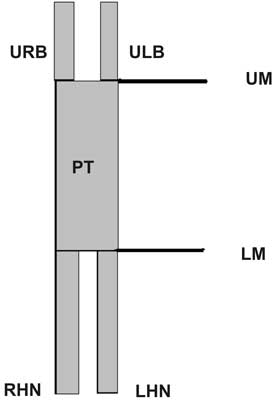

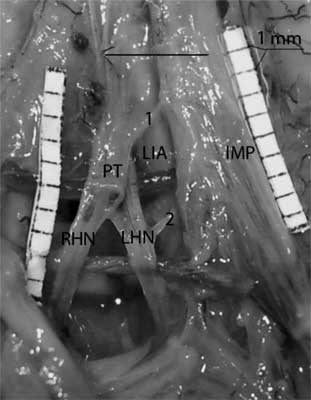

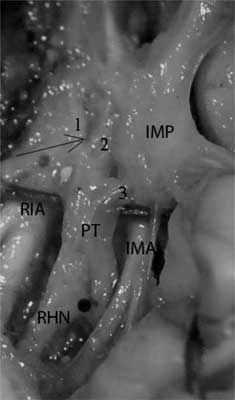

Fig. 1. The SHP structure.

URB – right upper branch; ULB – left upper branch; PT – plexus trunk; UM – upper margin; LM – lower margin; RHN – right hypogastric nerve; LHN – left hypogastric nerve.

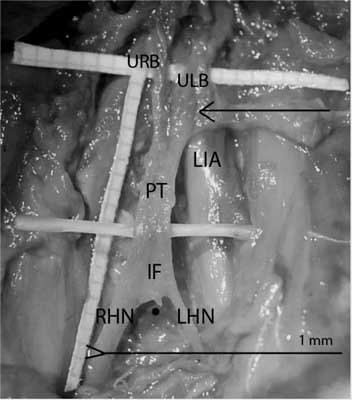

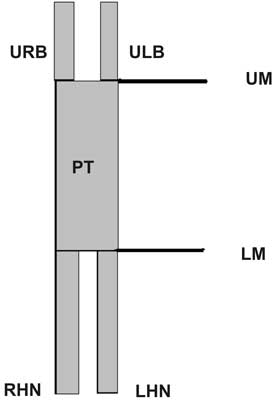

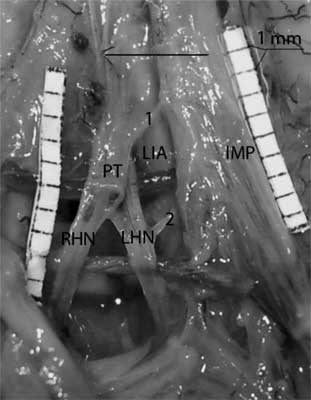

Fig. 2. Common morphology of the SHP.

PT – plexus trunk; IF – intercrural fibres; RHN – right hypogastric nerve; LHN – left hypogastric nerve; URB – upper right branch; ULB – upper left branch; LIA – left iliac artery; The arrow points at the aortic bifurcation; The black dot points the promontory.

In one case (the youngest fetus) the trunk of the superior hypogastric plexus was present as a single, thin filament.

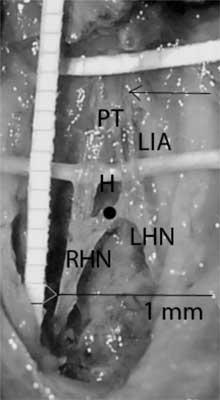

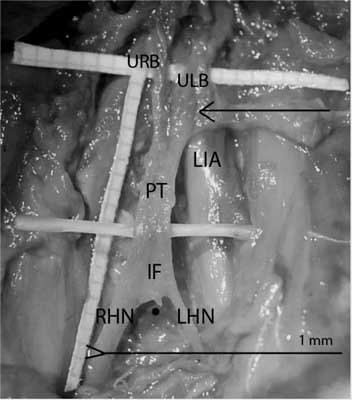

Fig. 3. SHP as a thin filament.

PT – plexus trunk; RIA – right iliac artery; RU – right ureter; The arrow points at the aortic bifurcation; The black dot points the promontory.

In two cases there was an opening (”hole”) in the centre of the trunk.

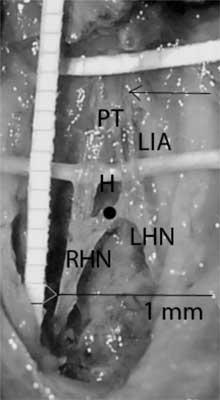

Fig. 4. Central "hole” in the body of SHP.

PT – plexus trunk; RHN – right hypogastric nerve; LHN – left hypogastric nerve; H – The "Hole” in a central part of the plexus; The arrow points at the aortic bifurcation; The black dot points the promontory.

The length of the plexus body varied from 3 to 13 mm. Minimal width of the plexus was 0.5 mm, maximal width was 7 mm. The authors found a positive correlation between length and width of the plexus (P 0.50) but no correlation between fetal age and length as well as width of the body was found.

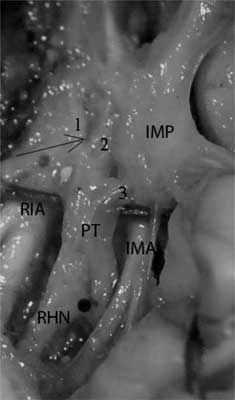

In 23 cases two branches connecting the SHP with the intermesenteric plexus were found. The left one was better developed in 15 cases. In two cases instead of well defined nerves the authors observed only diffused fibres. In the remaining cases, the two branches were similar. The authors did not observe any case of better development of the right branch compared to the left one. In one fetus they found a very wide first communicating fibre to the plexus of the low mesenteric artery which resembled a third branch of the dissected SHP structure.

The SHP always divided into two terminal branches, called the hypogastric nerves.

The lower margin of the plexus was usually located at the promontory level. In eight fetuses (8/25) it was located up to 3 mm above the promontory. The lower margin of the SHP was never found below the promontory.

The plexus origin, described as the distance between the inferior mesenteric artery and the upper margin of the plexus, was much more variable. The above-mentioned distance ranged from 3 mm to 9 mm. The plexus originated at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery in three cases (3/25). There was no statistical correlation (P -0.55) between the above-mentioned distance and the length of the plexus.

The next table presents the results of the statistical analysis.

Table 1. Results of measurements lenght and width in different fetal ages.

| age (weeks) | plexus length (mm) | plexus width (mm) |

| 1 | 16 | 5.5 | 3 |

| 2 | 17 | 7.5 | 2 |

| 3 | 18 | 11 | 3 |

| 4 | 18 | 5 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 19 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 19 | 5 | 2 |

| 7 | 20 | 6 | 3.5 |

| 8 | 20 | 12 | 7 |

| 9 | 20 | 4.5 | 2 |

| 10 | 20 | 8 | 4 |

| 11 | 22 | 4 | 2 |

| 12 | 22 | 6 | 3.5 |

| 13 | 22 | 6 | 2 |

| 14 | 22 | 5.5 | 2 |

| 15 | 23 | 11 | 2 |

| 16 | 24 | 13 | 2 |

| 17 | 25 | 5.5 | 2 |

| 18 | 25 | 3.5 | 2 |

| 19 | 25 | 11 | 4 |

| 20 | 25 | 8 | 2 |

| 21 | 25 | 9 | 4 |

| 22 | 25 | 6 | 3 |

| 23 | 26 | 5 | 1 |

| 24 | 28 | 11 | 2 |

| 25 | 28 | 9 | 3 |

Table 2. Results of statistical analysis.

| | min | max | med | corelation (Pearson) |

| age | DLIA | Pw | Pl |

| Plexus width | 0.5 | 7 | 2.6 | 0.06 | -0.06 | - | P 0.5* |

| Plexus lenght | 3 | 13 | 7.2 | 0.25 | P -0.5* | P 0.5* | - |

Legend:

Correlations significant at 0.05 level are marked with (*),

DLIA – distance from lower mesenteric artery,

PW – plexus width,

PL – plexus length.

Discussion

Until now only a few papers has explored the anatomy of the SHP. Common medical handbooks contain only basic information, which generally is not useful in the field of surgery (1, 2, 8). Some authors deny the sense of delineation of the SHP as a separate structure (13, 14). This is due to the difficulties in distinguishing the upper and lower limits of the SHP, especially among animals. Detailed dissection of the SHP fibres results in complete disappearance of its structure. Such a case is presented in the figures by Wo?niak or Sinielnikow (12, 14). However, dissection of only the upper and lower branches of the SHP leads to exposure of its central body and its margins, which can also be established even in the fetus (7).

It is composed of a dense layer of nerve fibres, lymphatic, fatty and connective tissues located in front of the aorta. The above-mentioned findings are in contrast to the results of some Russian authors, who described a rather diffuse form of this plexus (7, 12).

Fig. 5. The wide, single connection branch to the inferior mesenteric plexus.

1 – upper right branch; 2 – upper left branch; 3 – branch to the plexus from inferior mesenteric artery; IMP – inferior mesenteric plexus; CP – central body plexus; RHN – right hypogastric nerve; The arrow points at the aortic bifurcation; The black dot points the promontory.

Fig. 6. Another communication between SHP and inferior mesenteric plexus.

PT – plexus trunk; 1.2 – fibers communicating hypogastric and inferior mesenteric plexuses; RHN – right hypogastric nerve; LHN – left hypogastric nerve; The arrow points at the aortic bifurcation; The black dot points the promontory.

The spatial configuration of the SHP was generally similar to the adult one. (The SHP was found in a similar location in fetuses and adults). There were some minor differences in their spatial orientation. The fetal SHP was located in the midline while in adults it is displaced to the left (11). The lower central body margin of the SHP was typically set at the level of the promontory (it was displaced 2 mm above in eight cases) while it is more variable in adults, where it is placed both above and below this level (7, 11). In contrast to our findings, some authors define the aortic bifurcation as the level of the lower border of the SHP (14). It was reported that the hypogastric nerves´ bifurcation in fetuses was always moved upwards (to the 4th or 5th lumbar vertebra) compared to adults (7). We consider that this difference may be rather due to the different dissection methods. We did not isolate individual fibres constituting the central body since it would lead to obliteration of the plexus structure and make evaluation of its margins difficult.

The upper branches of the SHP have very rarely been described in the literature (7). Melman et al. observed two upper branches, of which the left one was significantly better developed (7). The authors confirmed their findings in the studies. We found two branches connecting the intermesenteric plexus with the SHP in almost all cases, and the left branch was better developed in the majority of fetuses (15/25 cases). However, we could not confirm some other results achieved by Melman et al. They observed that the right upper branch was mostly diffused and the left upper branch was solid (7). The authors found both upper branches to be well defined and rather symmetrical.

In all examined cases, the SHP divided into two lower hypogastric nerves, just like in adults. The authors observed interlacing fibres between the two nerves. This was shown in the previous reports (3).

Conclusions

The position of the plexus was constant; therefore its identification and preparation should not be difficult. The SHP inferior margin, which was marked by the level of its bifurcation, was a constant feature of the plexus. The length of the plexus was the most variable feature.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Appenzeller O: The autonomic nervous system. An introduction to basic and clinical concepts.North-Holland Publ. Co. Amsterdam, Oxford 1976. 2. Bochenek: Reicher Anatomia Człowieka, wyd. III, 1989. 3. Bruska M: Nerve cells and synapses in the human foetal hypogastric nerves. Folia Morphol 2005; 64: No. 3, pp. 199-211. 4. Calabrisi D: Observation on the autonomic outflow to pelvic ganglia and viscera in human embryo Anat Rec 1956; 124: 268. 5. Havenga K, DeRuiter MC, Enker WE, Weelvart K: Anatomical basis of autonomic nerve-preserving total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer, British Journal of Surgery 1996; 83: 384-388. 6. Kuntz A: The autonomic nervous system. Lea and Febiger 1953, Philadelphia. 7. Mel´man EP: Structure and functional importance of the superior hypogastric plexus; Arkh Anat Gistol Embriol 1958; 35(3): 29-37. 8. Mitchell GAG: Anatomy of the autonomic nervous system. E. and S. Livingstone LTD, Edinburgh and London 1953. 9. Nesbakken A et al.: M. Eri Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer, British Journal of Surgery 2000; 87: 206-210. 10. Raspagliesi F et al.: Nerve sparing radical hysterectomy: a surgical technique for preserving the autonomic hypogastric nerve. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 93: 307-314. 11. Jan van Schaik The Netherlands Nerve-preserving aortoiliac reconstruction surgery: Anatomical study and surgical approach. Jîurnal of Vascular Surgery 2001; 33, 5: 983-989. 12. Sinielnikow RD: Atlas Anatomii Człowieka. Medycyna 1967. 13. Wo?niak W: Nerwy pni współczulnych i ich sploty w jamach ciała w rozwoju ontogenetycznym człowieka. Roczniki AM w Poznaniu 1970; 4: 109-130. 14. Wo?niak W: The intermesenteric plexus Folia morph 1965; 24: 35-37.