*Sławomir Glinkowski, Daria Marcinkowska

Surgical treatment of rapidly advancing active ulcerative colitis: a case report

Leczenie chirurgiczne w gwałtownie postępującej aktywnej postaci wrzodziejącego zapalenia jelita grubego – opis przypadku

Department of General and Oncological Surgery, Health Centre in Tomaszów Mazowiecki

Head of Department: Włodzimierz Koptas, MD, PhD

Streszczenie

Wrzodziejące zapalenie jelita grubego należy do nieswoistych chorób zapalnych jelit o różnorodnym obrazie klinicznym. Ze względu na zaburzoną odpowiedź immunologiczną w obrębie tkanki jelitowej dochodzi do powstania rozlanego zapalenia, co prowadzi do występowania krwawień oraz biegunek. Podstawą rozpoznania jest obraz kliniczny oraz wynik badania kolonoskopowego, które potwierdza zapalne zmiany w obrębie jelita grubego.

Autorzy prezentują przypadek pacjenta przyjętego do oddziału po dwóch hospitalizacjach w innych ośrodkach, cierpiącego na aktywną postać wrzodziejącego zapalenia jelita grubego. Po wykluczeniu etiologii bakteryjnej oraz próbie leczenia zachowawczego na Oddziale Gastroenterologii pacjenta skierowano do Oddziału Chirurgicznego. W kolonoskopii wykonanej w trakcie poprzedniej hospitalizacji opisywano zmianę w okolicy zagięcia śledzionowego uniemożliwiającą uwidocznienie dalszego odcinka jelita grubego. Kolonoskopia wykonana na Oddziale nie potwierdziła występowania tej zmiany, a uwidoczniła liczne pseudopolipy. Z uwagi na gwałtownie postępujące wyniszczenie oraz anemizację, a także ze względu na brak poprawy po próbie leczenia farmakologicznego zdecydowano o wykonaniu pilnej kolektomii z wytworzeniem ileostomii końcowej. Po tygodniowym przygotowaniu pacjenta (żywienie pozajelitowe, przetoczenie KKCz) wykonano pankolektomię. Badanie histopatologiczne potwierdziło ostrą fazę wrzodziejącego zapalenia jelita grubego. W przebiegu pooperacyjnym doszło do masywnego zakażenia rany, które było leczone przez 14 dni terapią podciśnieniową (VAC). Pacjent na Oddziale Chirurgicznym był leczony 30 dni. W stanie ogólnym dobrym został wypisany do domu z zaleceniem dalszej opieki ambulatoryjnej.

Summary

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease with various clinical presentation. Due to an impaired immune response, diffuse inflammation develops in the intestinal tissue, which leads to bleeding and diarrhoea. The basis for diagnosis is the clinical presentation and the result of colonoscopy which confirms the presence of inflammatory lesions in the colon.

The authors present the case of a patient admitted to their department following two previous hospitalisations at other centres who was suffering from active ulcerative colitis. After bacterial aetiology of the disease was excluded and conservative treatment was attempted at a gastroenterology ward, the patient was referred to a surgical department. During the previous hospitalisation colonoscopy was performed in which a lesion was observed in the splenic flexure, which precluded the visualisation of the further part of the colon. A colonoscopy performed at the surgical department did not confirm the presence of that lesion; however, it did reveal multiple pseudopolyps. Due to rapidly progressing cachexia and anaemia and a lack of improvement following attempted pharmacological treatment, a decision was made to perform an urgent colectomy with end ileostomy. After a week-long preparation of the patient (parenteral nutrition, packed red blood cells transfusion), pancolectomy was performed. Histopathological examination confirmed acute phase ulcerative colitis. In the postoperative period massive wound infection developed, which was treated for 14 days with vacuum therapy (VAC). The patient was treated for 30 days at the surgical department. He was discharged in a good general condition and instructed to report to his outpatient care centre.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) belongs to the group of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). It has a multifactor aetiology and various clinical presentation. UC occurs everywhere in the world; however, the highest incidence is observed in the Caucasian population, particularly in Europe (UC: 505/100,000 in Norway; Crohn’s disease: 322/100,000 in Germany) and North America (UC: 286/100,000 in the USA; Crohn’s disease: 319/100,000 in Canada). UC incidence in Europe is approximately 10/100,000. The prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases has exceeded 0.3% in North America, Oceania and many European countries (1). The highest incidence of UC is observed between 20 and 40 years of age; however, the disease can occur both in children and in the elderly as well. Women and men are affected by UC at a similar rate, unlike Crohn’s disease, which is more common in women (2). Inflammatory bowel diseases are more common in individuals living in the city and performing office work (3).

Depending on the affected portion of the bowel patients can report different symptoms. The first symptom which may raise the suspicion of ulcerative colitis is most often diarrhoea (lasting usually over 6 weeks) with traces of blood. The number of bowel movements can be as high as 20 daily. When lesions do not extend beyond the rectum, the rate of bowel movements can be unaffected and the only symptom present can be constipation with traces of blood and sometimes abdominal pain as well. The disease is chronic, with periods of exacerbations and remissions.

The main procedure performed to diagnose the disease, monitor its course and conduct oncological surveillance is colonoscopy.

A clinical division of UC types is necessary to determine the point when local treatment is insufficient and systemic treatment needs to be introduced. In 2005, during the World Congress of Gastroenterology in Montreal a classification of UC based on the extensiveness of lesions in the colon was proposed (4).

This scale differentiates between:

– E1: proctitis, in which the disease is limited to the rectum (the proximal extent of inflammation is distal to the rectosigmoid junction). In this form of the disease the patients mainly complain of urgency to defecate, lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding and sometimes constipation,

– E2: distal/left-sided UC, in which the disease is limited to a proportion of the colorectum distal to the splenic flexure,

– E3: extensive UC, in which the disease extends proximally to the splenic flexure, sometimes involving even the whole colon (pancolitis) and sometimes reaching the distal part of the ileum.

In the case of extensive UC, the manifestations of the disease are more severe and lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding can occur. Patients experience urgency to defecate and traces of mucus and pus can occur in the stool. Patients also complain of nocturnal defecation and girdle abdominal pain, often located in the left iliac fossa, intensifying directly before and subsiding after defecation.

The clinical presentation of UC patients can be various. The authors present the case of a 61-year-old man in whom the disease had a short and very rapid course requiring aggressive treatment.

Case report

A 61-year-old patient was admitted to the Department of General and Oncological Surgery, Health Centre in Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Poland, with a diagnosed ulcerative colitis and colonic stricture in the splenic flexure reported on colonoscopy (suspected proliferative lesion) for further diagnostic investigation and possible surgical treatment. The patient complained of significant weakness, the loss of approximately 20 kilograms over two months and persistent diarrhoea with traces of blood lasting already three months with sometimes as many as 9 bowel movements a day. He denied any abdominal pain and vomiting, but did report a few episodes of nausea.

The patient underwent a cardioverter-defibrillator implantation surgery three years earlier due to second-degree atrioventricular block with pre-MAS syndrome. The patient also had a history of type 1 diabetes and cholecystectomy.

One month earlier, due to persistent bloody diarrhoea lasting over ten days the patient was hospitalised at the Department of Infectious, Tropical and Parasitic Diseases of the Department of Infectious Diseases and Hepatology. Based on tests infectious aetiology of the diarrhoea was excluded. An abdominal CT scan revealed the following: “The splenic flexure with irregularly thickened walls and irregular lumen, no peristalsis observed in this segment: a proliferative process suspected. Colonic wall thickening along the whole segment is visible with signs of inflammation”. Conclusion from the examination: “proliferative lesions in the gastrointestinal tract cannot be excluded”. A decision was made to perform another colonoscopy in order to collect a sample of the mucosa for histopathological examination. Due to poor preparation the colonoscope was inserted only up to 55 cm. Upon endoscopy, the colon was stiff and the mucosa of the descending and sigmoid colon and partly of the rectum was highly hyperaemic, reddened, friable and prone to bleeding upon contact with the examination device. Multiple sigmoid polyps of 2-5 mm in diameter could be seen. Multiple shallow diverticula were also found in the sigmoid colon. Histopathological examination of samples taken from the sigmoid colon, the descending colon and the rectum revealed lesions characteristic for active ulcerative colitis. Preliminary conservative treatment was applied: sulphadiazine and steroids. Due to anaemia 2 units of packed red blood cells were administered. Remarkable laboratory findings included an elevated level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 8.88 ng/ml (n: 0.00-3.40). After the treatment the patient was transferred to a gastroenterology department for further diagnostic investigation.

There, the patient underwent another colonoscopy in which the mucosa of the rectum, sigmoid and descending colon was oedematous on the whole surface, which was uneven and cobblestone-like and had numerous ulcerations of 5-6 mm in diameter, covered with fibrin and prone to bleeding upon contact at some spots. The mucosa in the splenic flexure was highly oedematous; for this reason, it was impossible to pass the colonoscope through. Once a smaller-diameter device was used, the proximal part of the transverse colon was reached and similar lesions were revealed. Samples were collected for histopathological examination, which confirmed the diagnosis of active-phase ulcerative colitis. Pharmacological therapy was introduced: oral and enema mesalazine, oral azathioprine, metronidazol, albumins, iron supplementation, a high-protein product to supplement the diet and an intestinal bacteria formulation. Glucocorticosteroid therapy was continued (Encorton 30-20-0 mg). The patient was discharged from hospital and he reported the next day to a surgical department for treatment.

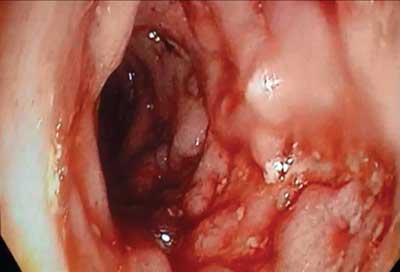

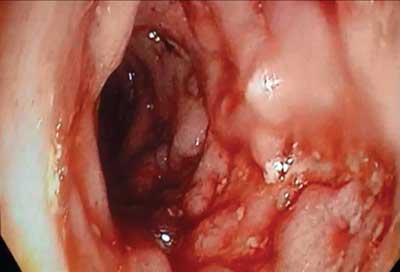

There, following bowel preparation, the patient underwent another colonoscopy which revealed lesions characteristic for active ulcerative colitis. The endoscopy technician passed the device through the splenic flexure without problems, finding no significant stricture that made it impossible to perform full colonoscopy on the previous occasion (fig. 1, 2).

Fig. 1. Colonoscopy image

Fig. 2. Colonoscopy image (splenic flexure)

Additional tests revealed the following remarkable findings: WBC = 3.1 x 103/mm3, RBC = 2.67 x 106/mm3, HGB = 8.0 g/dl, potassium = 2.9 mmol/l. The total serum protein level was 5.2 g/dl, therefore, due to cachexia, parenteral nutrition was included. The level of C-reactive protein (CRP) was 62.1 mg/l (n: 0.0-9.0). Due to the lesion reported in CT examination, a blood sample was also taken to check the level of CA 19-9: 34.28 IU/ml (n: 0.00-37.00) and CEA: 0.9 ng/ml (0-2.5 ng/ml); however, both were within the normal range. Based on the examination results and the severity of the patient’s complaints leading to rapid weight loss and progressing cachexia, a decision was made to perform urgent colectomy with end ileostomy. Due to the patient’s asthenia, the surgery was performed following patient preparation and a week-long total parenteral nutrition. Before surgery, the WBC level was 3.6 x 103/mm3; RBC was 3.43 x 106/mm3; HGB was 10.6 g/dl and the total protein level rose to 5.4 g/dl. A total of 4 units of packed red blood cells were administered to the patient before the operation.

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

29 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

69 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

129 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 78 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Ng S, Shi H, Hamidi N et al.: Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018; 390: 2769-2778.

2. Adams SM, Bornemann PH: Ulcerative colitis. Am Fam Physican 2013; 87(10): 699-705.

3. Wejman J, Bartnik W: Wrzodziejące zapalenie jelita grubego. Atlas kliniczno-patologiczny nieswoistych chorób zapalnych jelit. Termedia, Poznań 2011.

4. Kucharski A: Ocena przydatności skal endoskopowych do określania aktywności choroby u pacjentów z nieswoistymi zapalnymi chorobami jelit. Klinika Gastroenterologii, Żywienia Człowieka i Chorób Wewnętrznych, Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu 2012.

5. Langholz E: Current trends in inflammatory bowel disease: the natural history. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2010; 3(2): 77-86.

6. Bartnik W: Farmakoterapia colitis ulcerosa w fazie zaostrzenia i remisji – drugi konsensus europejski. Gastroenterol Klin 2013; 5(1): 1-4.

7. Truelove SC, Witts LJ: Cortisone in ulcerative colitis – final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J 1955; 2(4947): 1041-1048.

8. Prantera C, Marconi S: Glucocorticosteroids in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and approaches to minimizing systemic activity. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2013; 6(2): 137-156.

9. Lichtiger S: Preliminary report: cyclosporin in treatment of severe active ulcerative colitis. The Lancet 1990; 336: 16-19.

10. Becker JM: Surgical therapy for ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 1999; 28: 371-390.

11. Andersson P, Söderholm JD: Surgery in ulcerative colitis: indication and timing. Dig Dis 2009; 27: 335-340.