© Borgis - New Medicine 3/2009, s. 61-64

*Laszlo Papp, Erika Erdősi, Kornélia Helembai

Characteristics of student nurses´ attitudes towards ounselling: a descriptive study

University of Szeged, Faculty of Health Care Sciences and Social Studies, Department of Nursing, Hungary

Head: Dr Kornélia Helembai, PhD

Summary

Aim of the study. The aim of our study was to survey the BSc student nurses´ attitudes towards counselling.

Material and method. A quantitative survey, in a pretest-posttest design was conducted in our study. The participants completed the ´Counselling Attitude Scale´ before and after a 30-hour long ´Counselling in nursing´ course. The CAS contains 20 statements in four dimensions of the counselling attitude: acceptance, claiming of independence, problem-solving support, and leading of conversation.

The study sample was the third year BSc nursing students from the Nursing School of University of Szeged, Faculty of Health Care and Social Studies. 84 full- and part-time students joined the research. The data collection was carried out between February and April, 2008.

Results. We measured significant differences between the scores of the two student groups before and after the intervention course. Before the intervention, the full-time student got higher scores only on dimension ´claiming of independence´. After the intervention, the differences became more significant: The full time students got higher scores three out of four dimensions: ´acceptance´, ´claiming of independence´ and ´problem-solving support´.

Conclusion. Based on the results, the students are aware of the importance of client-centeredness. Average scores show the ambiguousity of the counselling attitudes in both student groups. The experiences of our study show that with well-planned and professionally achieved interventions, the distance between theory and the counselling practice could be reduced.

Introduction

Modern patient care is a complex activity, which demands the contribution of versatile, responsible nurses in the health care team [1]. Establishing a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship is an important goal for working with individuals in most nursing situations [2]. According to research findings, the patient´s perception of quality care is strongly related to interpersonal relationships [3]. The particular form of interpersonal contact that is known as ´counselling´ refers to any interaction where someone seeks to explore, understand or resolve a problematic or troubling personal aspect of a practical issue that is being dealt with. Counselling is an activity which takes place when someone who is troubled invites and allows another person to enter into a particular kind of relationship with them. McLeod describes nurses´ counselling as ´embedded counselling´, because the activity is incorporated within other work roles and tasks [4].

In the nursing literature, there is a considerable interest in the notion of the nurse developing counselling skills. Soohbany thinks there is a serious need for evidence of how nurses use counselling skills as part of their work [5]. Nupponen, based on the results of a study about Finnish primary health care, suggests that the individualization of the nursing process is less than complete [6].

There is also a certain interest in how student nurses learn counselling skills, and their relation to the activity itself. Burnard thinks that teaching nurses minimal counselling skills could be sufficient in enabling them to care for their patients in a positive and therapeutic way. The ´minimal counselling skills´ described by student nurses are listening and attending, using open questions, reflecting content and feelings, summarizing and checking for understanding [7].

The nurses´ attitude towards counselling basically determines the success of the nurse-patient interaction, and thereby the efficiency of nursing itself. An attitude study was carried out by Morrison and Burnard, examining the student nurses´ level of client-centeredness, using the 70-item Nelson-Jones and Patterson Counselling Attitude Scale. The results show that health visiting students and community psychiatric nursing students have significantly higher levels of client-centeredness than district nursing students. The results also showed that professional nurses got the highest, while staff nurses and state registered nurses had the lowest scores on the scale [8]. This attitude scale was tested in Hungary by Helembai, and according to students´ comments was found to be long and difficult to fill out [9]. Based on this experience, a 20-item Counselling Attitude Scale was created. Although the results of the two scales cannot be compared, the CAS could be a good opportunity to measure the student nurses´ counselling attitude, creating evidence for both nursing education and practice.

Aim of the study

The aim of our study was to survey the BSc student nurses´ attitudes towards counselling. Our aim was also to analyze the impact of education on counselling-related attitudes of student nurses, and furthermore to offer a new method for research in nursing to use it as an educational strategy as well.

Material and methods of the study

A quantitative survey, in a pre-test/post-test design, was conducted in our study. The participants were asked to complete the ´Counselling Attitude Scale´ (CAS) by Helembai, before and after a 30-hour long ´Counselling in nursing´ course. The CAS is designed specially for nurses, and contains 20 statements in four determining dimensions of the counselling attitude: acceptance, claiming of independence, problem-solving support, and leading of conversation. The persons have to choose between ´yes´, ´no´ or ´I don´t know´ in every statement [9].

The sample of the study was 84 full- and part-time, third year BSc nursing students from the Nursing School of the University of Szeged, Faculty of Health Care and Social Studies. We set the following inclusion criteria before sampling: the participants had to study nursing at BSc level in the Faculty, had to complete a 30-hour long ´Counselling in Nursing´ course between the two measurements, and had to consent to participate in the research. We excluded those nursing students who did not complete the intervention course. The data collection was carried out between February and April, 2008.

Before the intervention course, the participants filled out the Counselling Attitude Scale. Before the data collection, we outlined to the students the aim of the study, and the planned utilization of the results. They also received a detailed guide to the scale. The data collection was conducted anonymously, but for identification purposes, participants were asked to label the completed scale with a unique denotation. The labels were only used to pair the questionnaires which were completed before and after the course by the same participant.

After they had finished the intervention course, the participants were asked to complete the CAS questionnaire again. The response rate was 100%, and we could analyze all 84 participants´ answers.

During data processing, statistical methods were used. For general description of the data, frequency distributions and standard deviations were calculated. For data comparison, one sample T-test (to compare the two data sets from the same students), two independent samples T-test (to compare data from full-time and part-time students), and Pearson´s correlation were used. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows 11.0 software.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show both full- and part-time students´ scores on the attitude scale before and after the counselling course. Analyzing the scores separately, we can say that each of them has changed between the two measurements. Some changes could be identified as statistically significant.

Table 1. Full time students´ test scores before and after the Counselling course (N=37).

| Before | 1,297 | 1,054 | 0,838 | 0,216 | 0,351 | 1,027 | 1,946 | 1,324 | 1,73 | 1,432 | 1,108 | 1 | 1,108 | 1,378 | 1,73 | 0,162 | 1,162 | 1,946 | 0,946 | 1 |

| After | 1,703* | 1,676* | 0,622 | 0,946* | 0,216 | 1,595* | 1,919 | 1,27 | 1,351** | 1,568 | 1,324 | 1,541* | 1,216 | 1,514 | 1,865 | 0,189 | 1,514** | 1,946 | 1,27 | 0,811 |

* correlation is significant at p=0,01 level

** correlation is significant at p=0,025 level

Table 2. Part time students´ test scores before and after the Counselling course (N=47).

| Before | 1,5745 | 1 | 0,7872 | 0,234 | 0,1489 | 0,8085 | 2 | 1,0851 | 1,4043 | 1,3617 | 1,0851 | 1,0212 | 0,9574 | 1,1277 | 1,8511 | 0,1489 | 1,3617 | 1,8298 | 0,6809 | 0,9574 |

| After | 1,766 | 1,1702 | 0,8723 | 0,638* | 0,1702 | 1,234* | 1,9574 | 1,3191 | 1,5532 | 1,4468 | 1,1702 | 1,0638 | 1,277** | 1,0426 | 1,9149 | 0,1915 | 1,666* | 1,8936 | 0,8085 | 0,8936 |

* correlation is significant at p=0,025 level

** correlation is significant at p=0,05 level

The higher score (0.216 vs 0.946, p=0.001, full-time students; 0.234 vs 0.638, p=0.042, part-time students) of item 4 (´The nurse can understand the patient best as he imagines what he would do or feel in a similar situation´) after the counselling course shows that one element of the ´acceptance´ dimension was identified by the students as important, while other attributes of the same dimension did not change significantly. We have measured the same for item 6 (´Basically every patient has inner problem-solving abilities´). The answers to this specific question show greater value of one attribute within the dimension of problem-solving support (1.027 vs 1.595, p=0.001, full-time students; 0.809 vs 1.234, p=0.031, part-time students), while the other elements do not show significant changes. The answers to item 17 (´The content of the counselling conversation is what the patient identifies as the problem´) also show the significant change of one attribute within the ´leading of conversation´ dimension (1.162 vs 1.514, p=0.046, full-time students; 1.362 vs 1.666, p=0.042, part-time students). The other attributes of the dimension did not change significantly between the two measurements.

Based on the differences, we could say that the students have realized the importance of the basic principles of counselling. The analysis of the four attitude dimensions has shown ambiguity of the answers, and therefore of the attitudes too.

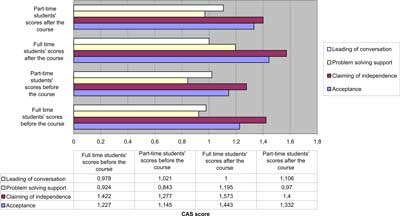

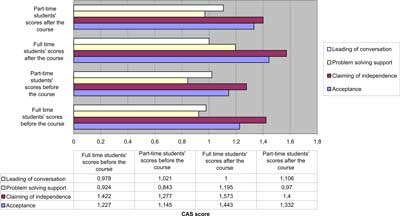

Table 3 shows the scores in all of the attitude groups before and after the counselling course. In the full-time students´ group, we measured significantly higher scores after the intervention course in dimensions ´acceptance´ (1.227 vs 1.443, p=0.014), ´claiming of independence´ (1.422 vs 1.573, p=0.052) and ´problem-solving support´ (0.924 vs 1.195, p=0.011). The part-time students´ answers showed significantly greater value of the dimension ´acceptance´ (1.145 vs 1.332; p=0.004).

Table 3. Scores of counselling attitude dimensions before and after the course.

| Before | After | Before | After |

| Acceptance | 1,227 | 1,443 | 1,145 | 1,332 |

| Claiming of independence | 1,422 | 1,573 | 1,277 | 1,4 |

| Problem-solving support | 0,924 | 1,195 | 0,843 | 0,97 |

| Leading of conversation | 0,978 | 1 | 1,021 | 1,106 |

| Full time students (N=37) | Part time students (N=47) |

Table 4 Scores on CAS dimensions before and after the counselling course.

| Before | After |

| Acceptance | 1,227 | 1,145 | 1,443 | 1,332 |

| Claiming of independence | 1,422 | 1,277 | 1,573 | 1,4 |

| Problem-solving support | 0,924 | 0,843 | 1,195 | 0,97 |

| Leading of conversation | 0,978 | 1,021 | 1 | 1,106 |

| Full time students (N=37) | Part time students (N=47) | Full time students (N=37) | Part time students (N=47) |

During our research, we also examined whether there are any statistically significant differences in the attitude dimension scores between full- and part-time students.

Before the counselling course, we measured a notable difference between the two student groups in the dimension ´claiming of independence´. Full-time students had significantly higher scores in this dimension (1.277 vs 1.422, p=0.087) than part-time students. After completing the counselling course, full-time students gained higher scores in ´claiming of independence´ (1.400 vs 1.573, p=0.090) and ´problem-solving support´ (0.970 vs 1.195, p=0.045) dimensions.

Discussion

According to Burnard and Morrison, student nurses think the most important counselling skills are being non-judgmental, being empathic and understanding of the patient. [8] This tendency could be noticed within our results. The attitude dimensions ´acceptance´ and ´claiming of independence´ – which are based on non-judgment and empathy – got significantly higher scores in both groups than ´problem-solving support´ and ´leading of conversation´.

Based on the answers about acceptance of the patient, the students are aware of the importance of client-centeredness. Average scores show the ambiguity of the attitude in both student groups. The scores are significantly higher after the completion of the counselling course, reflecting the respondents´ theoretical knowledge.

Claiming of the patient´s independence, and the application of his available inner resources to the problem-solving process, is one of the substantial principles of counselling. The answers relating to this attitude dimension reveal that the respondents recognized the significance of mobilization of the patient´s inner resources. After completion of the counselling course, we observed an increase in the dimension´s scores, which indicates recognition of the importance of this principle at a theoretical level.

The empowerment of the patient is a recent issue in the nursing literature. Kettunen analyzed 127 counselling sessions and her results show that the nurses´ facilitative strategies are the main elements of the patient´s empowerment. [10] The answers in our study show that the students are aware of their task in relation to the stimulation of the patient´s problem solving capacity. The prerequisite of the effective facilitation is a relationship based on partnership and cooperation. The power relations of the interactions in nursing frequently show the domination of the nurse, which leads to destabilization of the relationship´s balance. The nurse-dominated approach could be identified in the low scores of item 5 (´The nurse has to recognize through the conversation the other person´s problem and make him/her understood it fully´). The statements of the attitude dimension ´problem-solving support´ revealed incongruence between theoretical knowledge and practical application.

It is notable that the group of full-time students – who do not have working experience – in the dimensions ´claiming of independence´ and ´problem-solving support´ got significantly higher scores than the group of part-time students, who already have various nursing work experience. Our opinion is that the lower scores of the part-time students reflect the everyday routine and paternalistic approach of the current nursing practice. Resolving the contradiction between theoretical knowledge and practical experience is one of the tasks of education, as indicated by the growth in scores after the counselling course.

The counselling conversation is based on factors which were identified by the patient as problems. The role of the nurse during the conversation is orientative-facilitative, with supportive aspects, and its aim is to mobilize the patient´s own inner resources [9, 11]. Within the context of nursing, what patients require is exploration and/or resolution of focal problems. [5] The average scores of the ´leading of conversation´ dimension show ambiguity regarding this skill, and we could not measure significant advancement after the counselling course either.

Based on the positive changes of the attitude dimension scores, we conclude that the students recognized the importance of the basic counselling principles. The average values show the ambiguity of theoretical knowledge. This draws attention to students´ insecurity regarding basic principles´ translation into nursing practice.

Diagram1. CAS scores before and after counselling course.

Conclusions

1. Examination of the counselling attitude provides the possibility to obtain knowledge about the nurses´ relation to counselling. The problematic aspects of the nurses´ counselling could be identified with the help of the CAS scale.

2. In our recent study, the counselling-related attitudes of nurses seem ambiguous, with higher scores on practical, and lower on theoretical elements. This draws attention to the distance between theoretical knowledge and its practical implementation.

3. The higher scores of the second measurement show that with well-planned and professionally achieved educational interventions, this distance between theory and practice could be reduced.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Mészáros, J., Csóka, M., Hollós, S.: Clinical placement in nursing – a theoretical approach to the subject. (A klinikai ápolási gyakorlatok tantárgyelméleti megközelítése.) Nővér, 2004, 17(4); web access: www.meszk.hu/nover/2004/0404tart_hu.html; accessed 15.08.2009. (in hungarian). 2. Forchuk, C., Reynolds, W.: Clients´ reflections on relationships with nurses: comparisons from Canada and Scotland. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2001, 8: 45-51. 3. Fosbinder, D.: Patient perceptions of nursing care: an emerging theory of interpersonal competence. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1994, 20: 1085-1093. 4. McLeod, J.: Basics of embedded counselling, in Counselling Skill, Open University Press, UK, 2007. 5. Soohbany, MS.: Counselling as part of the nursing fabric: Where is the evidence? A phenomenological study using "reflection on actions" as a tool for framing the "lived counseling experiences of nurses". Nurse Education Today, 1999, 19; 1:35-40. 6. Nupponen, R.: What is counseling all about – Basics in the counseling of health-related physical activity. Patient Education and Counseling, 1998, 33: 61-67. 7. Burnard, P.: Acquiring minimal counseling skills. Nursing Standard, 1991, 5, 46:37-39. 8. Burnard, P., Morrison, P.: Client-centred counseling: a study of nurses´ attitudes. Nurse Education Today, 1991, 11:104-109. 9. Helembai, K.: Általános ápoláslélektan. A beteg-kliensvezetés pszichológiája (General nursing psychology: Psychology of patient/client management). Manuscript under publication, 2008. (in Hungarian). 10. Kettunen, T. et al: Developing empowering health counseling measurement – Preliminary results. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006, 64: 159-166. 11. Helembai, K.: Az ápoláslélektan alapkérdései (Basics of nursing psychology). I. ed. Budapest: HIETE Egészségügyi Főiskolai Kara, 1993. (in Hungarian).

Adres do korespondencji:

*Laszlo Papp

University of Szeged, Faculty of Health Care Sciences and Social Studies, Department of Nursing

6726 Szeged, Temesvári krt. 31., Hungary

tel: 00-36-20-568-9439

e-mail: papp@etszk.u-szeged.hu

New Medicine 3/2009Strona internetowa

czasopisma New MedicinePozostałe artykuły z numeru 3/2009: