*Michał Michalik, Adrianna Podbielska-Kubera, Agnieszka Dmowska-Koroblewska

Nasal septum perforation – new treatment methods

Perforacja przegrody nosa – nowe metody leczenia

Department of Otolaryngology, MML Medical Center, Warsaw

Head of Department: Michał Michalik, MD, PhD

Streszczenie

Perforacja to defekt przegrody nosowej objawiający się przerwaniem tkanki błony śluzowej w obrębie części chrzęstnej, kostnej lub obu części jednocześnie. W wyniku powstania perforacji dochodzi do zaburzenia transportu powietrza przez nos i upośledzenia fizjologii nosa. Powstają strupienia, krwawienia i świsty. Perforacje klasyfikuje się w zależności od ich wielkości, rodzaju ubytku i lokalizacji. Perforacje przegrody nosowej mogą mieć różne przyczyny: urazowe, jatrogenne, nowotworowe, związane ze współistnieniem chorób zapalnych, zakaźnych, zwyrodnieniowych lub autoimmunologicznych oraz nadużywaniem kokainy.

Ocena pacjenta z perforacją przegrody obejmuje szczegółowy wywiad kliniczny, badanie fizykalne, testy diagnostyczne i badania laboratoryjne. Podstawowe znaczenie w postępowaniu u pacjentów z perforacją przegrody ma wyleczenie choroby podstawowej. Drugi krok obejmuje zamknięcie perforacji. Perforacje można leczyć zachowawczo (farmakologicznie) lub chirurgicznie. Wybór sposobu postępowania zależy od etiologii, wielkości i umiejscowienia perforacji.

Najbardziej skuteczną metodą leczenia perforacji są zabiegi chirurgiczne.Chirurgiczne zamknięcie perforacji to zabieg trudny, powiązany z wieloma powikłaniami. Wszystkie zabiegi chirurgiczne oparte są na dwóch głównych zasadach: wytworzeniu płatów śluzowych, śluzowo-ochrzęstnych lub śluzowo-okostnowych bądź przeszczepie. Innym rozwiązaniem są nosowe protezy (obturatory). Dane wskazują, że najwyższe wskaźniki sukcesu uzyskuje się po przeprowadzeniu zabiegów chirurgicznych z wykorzystaniem lokalnych płatów błony śluzowej, przeszczepów z zastosowaniem powięzi skroniowej i ludzkich bezkomórkowych allograftów skóry właściwej.

Summary

Perforation is a defect of nasal septum manifested by the disruption of mucosa in the cartillaginous or bone part of nasal septum or in both of the parts at the same time.As a result, disruption of air transport through the nose and impaired nasal physiology occur. Crusting, epistaxis, and wheezing arise. Perforations are classified according to their size, type, and localization. There are many causes for nasal septum perforation: trauma, surgery, tumors, coexistence of inflammatory, infectious, degenerative, and autoimmune diseases, and cocaine abuse.

The assessment of a patient with nasal septum perforation includes detailed medical history, physical examination, diagnostic and laboratory tests. Treating the underlying disease is of primary importance. The second step involves closing the perforation. Perforations can be treated conservatively (pharmacologically) or surgically. The choice of approach depends on the etiology, size, and location of the perforation.

Surgical approach is the most effective. Surgical closure of nasal septal perforation is a difficult procedure associated with many complications. All surgical approaches are based on two main principles: creating mucosal, mucoperichondrial, and/or mucoperiosteal flaps or transplant. Prosthetic treatment is another solution. Literature data shows that highest success rate is achieved after surgical procedures with the use of mucosal flaps and temporal fascia transplants, as well as acellular human dermal allografts.

Introduction

Nasal septum is an important anatomical structure supporting the nose (1). Septum consists of three parts:

– membranous – limiting the entrance to the nasal vestibule, consisting of double skin layer,

– cartilaginous – cartilage of the nasal septum,

– bone – made of vomer bone and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone (2).

Nasal cartilage is connected with perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone through the posterior-superior margin. The cartilage is also connected with vomer and nasal crest of the maxillary bones through the posterior-inferior margin. The posterior-superior and posterior-inferior margin together form the posterior process (sphenoidal process), which is situated between vomer and perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone. Sphenoidal process is characterized by individual variability and has a key role in the development of nasal septum deviations (3).

Nasal septum perforation is a defect of the nasal septum (4). The resulting perforation is responsible for the airflow between the two parts of the nasal cavity (5). Perforation is a defect of the nasal septum manifested by the disruption of mucosa in the cartillaginous or bone part of the nasal septum or in both of the parts at the same time (1, 4).

Nasal septum perforations not only cause the desintegration of the septum, but also impair the nasal physiology (4). Perforations are a cause of breathing disorders and impaired nasal airflow (6). In addition, large anterior perforations may result in the loss of dorsal support and deformation of the external nose (7).

Normal airflow in the nasal cavity is of laminar nature. In nasal septum perforations, laminar flow is disturbed and substituted with turbulent flow. The turbulent flow is the main cause of crusting, epistaxis, and wheezing (4). The severity of air turbulence is proportional to the size of perforation (7).

Nasal septum perforations occur relatively often. Reports from Sweden estimate the prevalence of perforations in the general population to be 0.9% (8). Other sources indicate that perforations are present in about 1% of ENT patients (9). The prevalence of nasal septum perforations is probably higher than 1%, and the underestimation may be a result of the fact that close to two thirds of the patients remain asymptomatic and never visit a medical professional (1). Nasal septum perforations that remain untreated for a long time may contribute to the destruction of the ciliated epithelium, and thus contribute to dryness of the nasal mucosa (10).Nasal septum perforations are rare in pediatric population. While the symptoms, etiology, and treatment methods of nasal septum perforation in adults are well described in the literature, reports concerning pediatric population are still limited to a small number of cases, and scientific papers consist mainly of case reports (10).

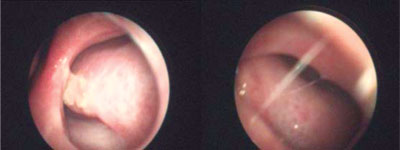

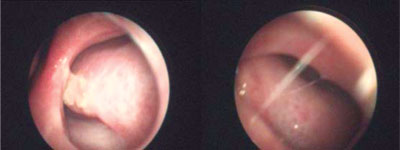

Fig. 1. Nasal septum perforation in a patient of the MML Medical Center

Classification of perforations

Perforations are classified according to their size, type, and localization (anterior, mid septal, posterior) (8). Anterior perforations are the most common (92%), and less than 10% of perforations are located posteriorly. Posterior perforations are usually asymptomatic and caused by systemic diseases (11). Perforations may have different shapes: from linear to round or oval. Depending on the size, perforations can be divided into small (< 1 cm diameter), medium (1–2 cm), and large (> 2 cm) (12).

Data concerning large perforations is limited. In 2007, Døsen i Haye assessed 197 patients treated for septal perforations in the years 1981–-2005 (100 men and 97 women). The authors confirmed the presence of large perforations in 11% of the studied patients (12). Islam et al. (7) introduced a classification of perforations depending on its height. A perforation that is lower than one third of septal height (0–8 mm) is classified as small, perforations ranging between one third and two thirds of the septal height (9–18 mm) – are classified as medium, and perforations larger than two thirds of septal height – as large. These proportions are changed in patients with a large nasal hump or a collapsed nasal bridge (7). Sapmaz et al. (6) measured the longest vertical dimension of the perforation and vertical length of the septum in the plane in which the perforation is largest. By comparing these two measurements, they created a classification consisting of two groups. The authors believe that the new classification may help surgeons determine the exact size of perforation before the procedure, which will result in a better choice of method of treatment and selection of an appropriate surgical approach, as well as help estimate the number of expected surgical procedures (6).

Symptoms

Perforations contribute to the occurrence of the turbulent airflow in the nasal cavity, which causes dryness to the nasal mucosa. This leads to many symptoms, including crusting, dryness, recurrent epistaxis, nasal congestion, discharge of an unpleasant odor, headache, and wheezing (1).

The symptoms of septal perforation depend on the localization, size, and cause of perforation. Small perforations located posteriorly may be asymptomatic. Anterior perforations are usually associated with wheezing (7). Wheezing occurs more frequently in patients with smaller perforations, whereas epistaxis and crusting are more common in patients with larger defects. The more anterior is the perforation located, the more severe the symptoms (13). Up to 39% of patients with perforation may remain asymptomatic (9).

Chang et al. conducted a study on a group of children with septal perforation, the majority of whom complained of crusting (73%). Crusting was mainly due to dryness of the nasal mucosa secondary to turbulent airflow. In more than half of the patients, epistaxis was observed, and one third of the children complained of nasal congestion. The opposite situation usually occurs in adults, in whom epistaxis is initially observed (in 58%), and crusting follows (43%) (10).

Causes

The pathogenesis of nasal septum perforations consists of four stages:

– in the first stage, there is a local inflammatory reaction resulting in mucosal damage, erythema, edema, and crusting;

– in the second stage, a reduction in vascularization along with infiltration with inflammatory cells is observed, which leads to cartilage ischemia and loss of mucosa and submucosa;

– the third stage involves cartilage ulceration and necrosis;in the last, fourth stage, perforation borders are covered with atrophic epithelium prone to bleeding and crusting (11).

There are many causes for nasal septum perforation: trauma, surgery, tumors, coexistence of inflammatory, infectious, degenerative, and autoimmune diseases. What is more, nasal decongestants and cocaine abuse may also contribute to the formation of a perforation (4, 8).

Other causes of septal perforation include complications after embolization, foreign bodies in the nasal cavity, chronic use of nasal cannulas, and systemic diseases: sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosis, tuberculosis, AIDS, Crohn’s disease, leishmaniasis, celiac disease, as well as invasive fungal sinusitis, renal failure, nicotinism, and targeted biological therapies used for treatment of malignant and non-malignant tumors (bevacizumab, methotrexate) (8). The perforation of nasal septum is most often caused by surgery, mainly septoplasty, blunt trauma, and cocaine abuse (12). In about 39% of patients, the cause of the perforation are nose and face injuries (11). Septal perforation occurs when the blood supply to the nasal cartilage is closed on both sides of the septum in approximately the same localization (9).

Damage to nasal mucosa leads to inflammation and further disintegration of the mucosa and aggravation of the infection. The final destruction of the mucosa is responsible for the loss of cartilage blood supply, which results in a perforation. Health care professionals should be aware of the risks of mucosal damage associated with medical procedures within the nose, such as cauterization. It is suspected that bilateral cauterization is more traumatic (10). Cocaine abuse may result in vasculitis, skin necrosis, lung diseases, and other conditions. Long-term cocaine abuse is also responsible for intranasal damage, including damage to the lateral wall of the nasal cavity and/or damage to the hard palate (11). The prevalence of nasal septum perforation in cocaine addicts is 4.8%. The damaging effects of cocaine on intranasal structures may result from an increased local cellular apoptosis, which is time- and dosage-dependent. In addition, the blockade of catecholamine reuptake causes vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction may lead to mucosal damage and ulceration. Long-term ischemia causes necrosis of the nasal mucosa and septum (11). The influence of vasoconstrictive drugs on nasal septum perforation has not been sufficiently documented. Experiments on animal models using high doses of oxymetazoline showed a significant increase in the prevalence of septal perforations. Docuyuku et al. (11) observed that rats treated with high doses of oxymetazoline showed a significant increase in the incidence of ischemic lesions, hyperemia, arterial thrombosis, necrosis, and ulcerations when compared with rats receiving saline solution. These results have not been confirmed in humans.

Harmful working conditions may also contribute to the occurrence of nasal septum perforations. The prevalence of septal perforations resulting from occupational exposure to chemical substances is often underestimated. The most frequently reported damage are related to chemicals with caustic properties. Perforations have also been reported in workers exposed to toxic heavy metals, such as chromic acid. The prevalence of nasal septum perforation is this groups varies between 20 and 30% (11). Nasal septum perforation can also be caused by syphilis. During three stages of syphilis, nasal cavity may be involved to a different extent: primary syphilis is usually characterized by few nasal symptoms,in the secondary syphilis, acute rhinitis accompanied by profuse nasal secretion and irritation of nasal mucosa is observed, tertiary syphilis may manifest with an advanced nasal involvement with condylomas, septal perforations, and deformation of the nasal bridge (11).

A few cases of nasal septum perforation in patients with AIDS have been reported. Acute and chronic rhinitis may be the first symptom of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The exacerbation of allergic rhinitis is very common in this disease. Opportunistic infections may also occur. Nasal polyps and tumors, including lymphomas and Kaposi’s sarcoma, are quite common in HIV-positive patients (11). There is a relationship between fungal sinusitis and nasal septum perforation. Fungal sinusitis usually occurs in immunocompromised patients. The disease is characterised by a progressive infiltration of blood vessels and thrombosis, followed by necrosis and tissue destruction. Patients often complain of epistaxis, facial pain, edema, and fever. The disease progresses rapidly and may result in ulceration of the mucous membrane, perforations and gangrene of the nasal septum with cranial nerve palsy, vision loss, and proptosis (11). In 60 to 90% of patients with systemic vasculitis, respiratory symptoms are observed. Over 25% of all patients report symptoms such as: crusting (69%), chronic sinusitis (61%), nasal congestion (58%), mucosal discharge (52%), epistaxis, and nasalgia. Untreated, this condition may later contribute to the destruction in the middle line of the nose. Bone destruction initially affects only nasal septum, but may gradually spread to conchae, sinuses, and other structures. Patients with a locally aggressive form of the disease may have symptoms of nasal septum necrosis, which results in the loss of support of the septum and collapse of the nasal cartilage. In 23% of patients, nasal bridge deformation occurs (11).

Among autoimmune diseases characterized by nasal symptoms, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) seems to be the main reason for nasal septum perforations (48% of all cases of autoimmune diseases) (11). The occurrence of nasal septum perforation is common in some neoplasms, especially tumors associated with nasal cavity. Monoclonal antibody inhibitors prevent angiogenesis in the nasal septum cartilage, which may contribute to the formation of a septal perforation (11). In children, trauma and iatrogenic factors together cause over 50% of all septal perforations. Trauma usually occurs as a result of children picking their nose. Using suction devices during infections and nasogastric tubes may also contribute to the occurrence of septal perforation (10). If the cause of nasal septum perforation cannot be identified, neoplastic and autoimmune causes should be taken into account, as they are present in 20% of pediatric patients with septal perforations. The most common malignant tumors include lymphomas and leukemias. No tumors of the nasal area are observed in children (10).

Bacteriology

There are reports in the literature concerning rare but serious complications following septoplasty, including toxic shock syndrome, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. Prophylactic antibiotics are usually sufficient to prevent post-operative infections. Sometimes, however, they are ineffective. The majority of the infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, which is part of the normal bacterial flora of the nasal cavity in about 50% of the population. There are also reports of patients with perforations caused by other pathogens, e.g. a case report of a patient who had undergone septoplasty complicated by tissue necrosis and perforation of the nasal septum caused by Enterobacter cloacae (14). It is speculated that the frequent occurrence of S. aureus in patients with nasal septum perforation may result from the transfer of bacteria from healthcare professionals. However, this seems unlikely, as the prevalence of S. aureus among hospital staff is similar to that observed in the general population. The higher prevalence of S. aureus in patients with nasal septum perforation may be a result of a greater susceptibility of these patients to bacterial colonization and a greater tendency to the chronicity of the infection (15). The use of prophylactic antibiotics in nasal surgery is preferred by most medical doctors. However, recent studies have shown that there is still no evidence of the need for administration of antibiotics before every surgical procedure. Some researchers have not observed a significant difference between groups of patients who had or had not received antibiotics post-operatively. Therefore, they suggest that nasal surgery may not require antibiotic prophylaxis due to a low risk of infection (14). C. pseudodiphthericum and C. propioniquum are species that are frequently part of human oropharyngeal flora. Although these bacteria are characterized by a low virulence, they may contribute to poor clinical outcomes, especially in patients with immunodeficiencies and endocarditis. An inverse relationship between the prevalence of Corynebacterium and S. aureus have also been described, as severe colonization with Corynebacterium prevents colonization with S. aureus (16). In patients who inhale cocaine nasally, nasal septum perforations with colonization with anaerobic bacteria is most often caused by ideal environmental conditions, which combine a reduced amount of oxygen, inflammation, irritation, and open wound. Staphylococcus aureus is a common bacterium occurring in this group of patients (17).

Diagnosis

Conducting the diagnostic process in patients with nasal septum perforation is necessary for detecting causes of the problem (8). Patients usually report to a specialist when the first symptoms occur (18).

The assessment of a patient with nasal septum perforation includes:

– detailed medical history,

– physical examination,

– diagnostic and laboratory tests (11).

Collecting medical interview aims to gather information on previous surgeries and nasal intubations, nasal injuries, nose picking habits, irritants in the work environment, the use of intranasal drugs, and the co-occurrence of systemic diseases or neoplasms. Physical examination of the nose starts with an assessment of the external nose (8). Physical examination should include a full assessment, including endoscopic examination of the sinuses (11). Performing endoscopic examination may be helpful in the visual assessment of nasal septum perforation, as well as in assessing the irregularity of the mucosal structure (8). It is also advised to evaluate and measure the remains of cartilaginous and bone support (11).

Imaging examinations are an extremely important element of the diagnostic process and are performed both before and after surgery to obtain as much information about the structure of the nose as possible, as well as to determine the degree of damage to bone and mucosa. This is necessary for planning the reconstruction surgery and maximizing the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy (8).

Imaging studies include sinus computed tomography and chest x-ray (11). Some anatomical structures, especially nasal septum, are not optimally visible in computed tomography, nor in 2D magnetic resonance in the standard axial and sagital planes. Using 3D magnetic resonance provides a better visualisation of soft tissues when compared with computed tomography, and does not expose a patient to a harmful radiation (8). Laboratory tests include complete blood count, rheumatoid factor, tuberculin test, serological tests for syphilis, ANA and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA, c-ANCA) (19). For patients who use intranasal cocaine, the urine and, if possible, hair, must be tested for the presence of catabolic products of cocaine. In these patients, it is advised to postpone the operation until one year after cessation of cocaine use (8). In every patient, vertical dimension of the septum and of the perforation should be measured. The ratio of these two values may help to assess the size of the perforation more realistically. A 2 cm long perforation in a patient with a 3.5 cm long septum may not cause difficulties during surgery, whereas a 2 cm long perforation in a patient with a 2.5 cm septum may be difficult to close (6).

Although it is important to reduce the patient’s subjective symptoms, objective assessment of nasal physiology should also be performed. Pre- and postoperative assessment of the physiology of the nasal septum enables to compare the results of different surgical procedures and may contribute to determining the best method. It is recommended to perform rhinomanometry and examine airway resistance based on the measurement of the airflow through the nose and of the pressure generated by the air flowing through the nose (4).

Treatment

Septal perforations do not close spontaneously – on the contrary, existing perforations tend to increase their size (1). The natural process of tissue healing is not observed. The majority of patients with nasal septum perforations remain asymptomatic, especially in cases of perforations located in the deeper, osseous part of the septum. Anterior perforations, located in the cartilaginous part, usually manifest with troublesome symptoms (13). Symptomatic perforations (rhinitis, epistaxis, etc.) are usually treated surgically. Surgery should always be preceded by a detailed analysis of the perforation size, especially of its height. In fact, it should always be assumed that the perforation is larger than the measurements indicate. This allows a more accurate selection of the required mucosal flap or transplant (20).

The closure of nasal perforation is a challenge for both the surgeon and the patient. The aims of the surgery include a good aesthetic effect, but above all, the restoration of the anatomical and functional integrity of the nose (8). The success of the surgical procedures is usually determined by the anatomical closure of the perforation and the reduction or resolution of symptoms (4).

The first step in the management of patients with nasal septum perforations is treating the underlying disease that has led to the perforation. The second step involves closing the perforation in order to restore the physiological environment of the nasal mucosa (13).

Perforations can be treated conservatively (pharmacologically) or surgically. Due to the complex etiology and variable size and location of the nasal septum perforations, there is no single procedure to be used for all cases (5). Individually tailored surgical and conservative treatment approaches are used with varying success rate (4).

Conservative treatment of nasal septum perforation involves the use of moisturizing agents and emollients that help to relieve the symptoms of the perforation. It is also possible to perform nasal irrigations with isotonic saline solution and apply antibiotic ointments (13, 21). After nasal discharge or unpleasant odor have resolved, the patient may continue to use irrigations with saline solution without antibiotic therapy (18). If the lesion cannot be treated conservatively, surgical approach must be taken into account. Before the procedure, the ENT specialist must identify the cause of the nasal septum perforation, which in most cases is iatrogenic or idiopathic. Then it is possible to qualify the patient for surgery and determine the most appropriate surgical approach that is tailored to the specific needs of a patient. It has been suggested that in asymptomatic patients, surgery is not necessary (18). Surgery remains the most effective method of treatment of septal perforations, because successful, complete closure of a perforation eliminates the symptoms and the need for further treatment (1). In the surgical approach, the effect of the procedure is influenced by the size of the perforation, the use of appropriate tissue to fill the perforation, and surgeon’s experience (6). Surgical procedure may not give satisfactory results in perforations caused by cocaine abuse, granulomatosis, nose picking, and cauterisation (6). Contraindications to surgery also include health conditions in which general anesthesia is a serious risk factor (18). Surgical closure of nasal septal perforation is a difficult procedure associated with many complications. Many factors contribute to surgical success, including precise determination of the aetiology, proper localization of the lesion, and selection of the most appropriate method. Patient care before, during, and after surgery also plays an important role in the final clinical outcome (8). All surgical procedures for nasal septum perforation closure are based on two main principles: creating mucosal, mucoperichondrial, and/or mucoperiosteal flaps or transplant (18).

Measuring the size of perforation before surgery is an important factor in planning the procedure (21). Small- or medium-sized septum perforations are usually closed using local flaps with or without transplant, and the treatment is successful in 85–100% of cases. Using mucoperichondrial or mucoperiosteal flaps from the septum wall or the bottom of the nasal cavity is not a good solution in perforations characterized by a large vertical size. In this case, the tissue below and above the perforation may not be sufficient to completely close the perforation without causing too much tissue stress (21).

Large perforations with a diameter above 20 mm are characterized by a high complication rate. Surgical techniques that have been created for the closure of large perforations have their disadvantages: they leave a visible external scar, perforation is often not closed with a physiological airway epithelium, sometimes multiple procedures are needed or an oronasal fistula has to be created. In this context, using local mucosal flaps remains the best method, even in cases of large perforations, because it does not have any of the disadvantages listed above (21).

For small perforations, it is not necessary to make release incisions. In cases of larger perforations, the flaps will not close without release incisions under nasal turbinates and intranasally in the anterior part of the bottom of the nasal cavity. Thanks to this, it is possible to transfer a rotated large mucosal flap, pedunculated posteriorly. If the flap still does not close the septal perforation, further surgical management is necessary: further dissection of the flap from the lower surface of the lateral nasal cartilage and a release incision along the top of the septum (19). Usually after the procedure, a teflon nasal dressing is used. The dressing is usually left for about 2–3 weeks. In addition, a cast is applied for one week. After removing the dressing, it is necessary to moisturize nasal cavities and perform control examinations (after 3 and 12 months). The authors state that this technique was effective in 95% of perforations measuring 2 cm or less (19).

Surgical procedures may use an open or a closed approach (8).

An open approach is believed to provide a routine removal of all damaged fragments and reconstruction in areas located at the edge of the perforation. Using open approach in nasal septum perforations ensures a better access and facilitetes the procedure in cases of a big perforation or a posterior perforation, with the possibility of rhinoplasty. However, it is often not possible to obtain flaps that are big enough to close the perforation. To prevent this, some authors suggest performing reductive septorhinoplasty to obtain mucosa for closure of the septal perforation (8). Open surgical approach enables to close over 90% of perforations measuring less than 3 cm (18).

Fod et al. (8) have confirmed that when using the external surgical approach, difficulties in effectively closing the perforation are directly proportional to the size of the perforation. The advantage of the closed approach is the fact that is does not leave an external scar, as there is no external incision (12). The disadvantages of the closed approach, associated with a narrow and deeply located operating field, can be overcome with endoscopic support. Endoscopic nasal surgery is used to close medium (0.5–2 cm) and big nasal septum perforations (12). Sometimes, larger perforations may require septorhinoplasty (5). The use of endoscopic nasal surgery significantly improves the visibility of the structures and increases the precision of the surgical procedure (12). Endoscopic approach may even be effective in treatment of large perforations, but it requires significant skills from the operator (5).The closed approach is extremely effective in cases of perforations measuring from 2 to 4 cm. It enables the highest precision at all stages of the procedure, and, above all, it allows for a perfect closure of both anterior and posterior perforations, which give the most onerous symptoms. This approach is not a contraindication for other surgeries that may be performed during the same procedure or later (12). The surgical methods have been modified over the years. At the beginning of the 1950s, prostheses were first used for nasal septum perforation closure. Although the materials used for prostheses have been improved over time, they are invariably poorly tolerated and perceived as foreign bodies by the organism. Prostheses have been used mostly in patients in whom surgery was contraindicated (18). More and more researchers have been proposing new, more innovative closed-approach solutions. Seiffert et al. (22) used flaps obtained with a crescent-shaped incision, 1 cm from the perforation margin (18). Meyer et al. (23) used a composite flap from the oral vestibule. This approach was supposed to be used for closure of large perforations. Since the 1980s, modifications regarding the open approach have also been introduced. At that time, Strelzow et al. (24) described their open-approach method for the first time, and in 1982, they presented a case report of a patient with a large vertical perforation.

In 1989, Eviatar et al. (25) proposed the use of the outer ear cartilage together with perichondrium as a transplant material. In the following years, Hussain and Kay described the creation of a “sandwich” with cartilage inside and mucosoperichondrial flaps on the outside.

The next breakthrough was the introduction of expanders. In 1995, Romo et al. described the use of expanders in 5 patients with large nasal septum perforations (diameter > 4 cm). In all cases, full closure of the nasal septum perforation was obtained. The results were evaluated one year after the surgery (18). In case of large perforations, permanent repair is not always possible. In order to close septal defects, tissues from nasal turbinates and auricle or rib cartilage are used, sometimes as allogenous grafts (8). Autologous cartilage from the auricle or a rib is still considered the best material for septal perforation closure (12). If possible, the transplant should be covered with mucosocartilaginous flaps (20). Disadvantages of using cartilage for closure of septal perforations include a limited amount of material and the fact that previous nasal trauma and surgery decreases the quality of the cartilage. The procedures have only one stage and are short in duration, however, they require an experienced staff. This approach is suitable for closing perforations up to 25 mm vertically (1). Placing autografts (bones or cartilages) between flaps for support purposes is an effective method of treatment of septal perforations measuring 2–3 cm with a 90% success rate. It has been found that it is possible to achieve complete closure of a perforation with polyethylene implant covered with mucosa. Using cartilage from the nasal septum or plate of the ethmoid bone (when nasal septum cartilage is not available) may lead to a success rate of up to 95% (6). In case of implants, autologous and homologous tissues are used, including temporal fascia and acellular human skin allograft (21). The use of cartilage (especially autologous cartilage) provides better support for the regenerating musoca than fascia (1). Kridel et al. (26) used human dermins graft (Alloderm) in 12 patients with perforations measuring < 3 cm. The researchers obtained a success rate of 92% – the complete closure of perforation in 11 out of 12 cases.

Lee et al. (27) used an autologous skin transplant in 14 patients with small and medium septal perforations. Full closure was achieved in 64% of cases, and partial closure – in 16%. Bryan et al. (28) used small intestinal mucosa as a transplant. In 10 patients with nasal septum perforation measuring between 0.4 and 2 cm, excellent results were achieved, and full closure occurred in all cases.

Krzeski et al. (19) suggest that in case of large perforations, it is advised to perform multistep operations using complex cheek skin flaps. The procedure described by the authors had 3 stages. The first stage involves placing the auricular cartilage under cheek mucosa, which is cut off on the cheek surface of the upper lip. Then, a smaller flap of adjacent mucosa is slid under the main flap, so that it surrounds the cartilaginous graft. Between the flaps, auricular cartilage is placed. This composite flap is left for 5 weeks. In the second stage, the flap is transferred and sutured into the septum defect, and in the third stage, after 5 weeks, the pedicle of the flap is cut off. Based on the authors’ own experiences, an algorithm resulting in the 90% success rate was created. The algorithm determines the the treatment method based on the size and localization of the septal perforation. For small perforations (0–1 cm) situated in the anterior part of the septum, intranasal access with mucosal flap with a double pedicle is preferred. If the perforation is located posteriorly and in case of medium-sized perforations (1–2 cm), the authors suggest external rhinoplasty with the use of mucosal flaps with posterior pedicles. For large perforations, individually matched implants are recommended. In the abscence of therapeutic success using this method, the authors indicate the need for a three-stage procedure with the use of a complex cheek flap (19).

Alternatively to surgical closure, nasal prostheses made of acrylic, plastic, and silicone can be used (13). Mechanical obturation using one- or two-part silicone diaphragm (Xomed) eliminates epistaxis and wheezing and reduces nasal congestion. Contraindications include acute infections, osteomyelitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, neoplasms and extremely large perforations (13).

The obturator is a prosthetic device used for a temporary closure of the perforation. The obturator is installed under local anesthesia. The device can be left for 1 year or longer (11). Obturators are made of various materials: rubber, acrylic, resin, silicone, and can have a standard shape or are individually tailored. The advantages of this method include its easiness and the ability to discharge the patient on the day of surgery, as the procedure is performed under local anesthesia (13). The main problem associated with obturators is their poor fit, which causes discomfort or contributes to crusting. The solution is to create individually tailored elements based on computed tomography scans (19). The use of obturators is associated with multiple complications, including nasal pain, epistaxis, irritation, crusting, and may contribute to the erosion of perforation edges and enlargement of the defect (11). Luff et al. (29) report that despite symptom reduction, this method is poorly tolerated by patients in 50% of cases. However, research conducted by Mullace et al. (13) has shown that patients tolerated the obturators well and reported symptom improvement. No infections and discomfort have been observed and only one of 15 patients required the removal of the obturator. The follow-up after 3 and 43 months showed that the device was well tolerated by 11 patients. Using silicone obturators may be useful in patients in whom local or systemic comorbidities make it impossible to perform surgical reconstruction (13). An obturator, which is a foreign body, may contribute to the occurrence of inflammation, nasal congestion, and nasal discharge. Obturators reduce symptoms in majority of the patients, but they do not cure the disease. For this reason, some patients ask to remove them after a short time (6).

Significantly better results are obtained in patients treated with mucopericondrial and mucoperiosteal flaps when compared with patients treated with obturators. These results are consistent with Gillies theory (30), which states that where there is tissue damage, similar tissue should be used to repair it. The advantage of surgical reconstruction over obturators was confirmed both in the post-operative follow-up, as well as in the quality of life questionnaires (6).

For large nasal septum perforations, Daneshi et al. (20) used an open surgical approach involving a titanium diaphragm. All the patients received systemic antibiotics one week post-operatively. The dressing was removed on the 5th day after the procedure. The patients were instructed to moisten the nasal mucosa with a spray (20). Titanium membranes and mucoperiosteal flaps used together for the treatment of nasal septum perforation were first described in 2006, with good clinical outcome in 11 patients. It is a relatively simple technique that has a success rate comparable or better than other techniques. One of the main advantages of the technique is the lack of tension in the cutting line (20). The majority of patients with nasal septum perforations had previously undergone septum surgery with cartilage removal. In these cases, the use of titanium diaphragm has a clear advantage. The titanium membrane helps to eliminate the risk of deformation of the nasal bridge, which is a frequent complication of surgical procedures on large septal perforations (20). Septoplasty is burdened with a risk of the mechanical weakening of the septum cartilage, which may result in the loss of its stabilizing function (20). When looking for a solution, it was found that polydioxanone may be effective. Polydioxanone is safe, degraded by hydrolisis and completely absorbed by the body, which prevents long-term complications associated with other artificial implants. Polydioxanone plates are available in various sizes and thicknesses and have been successfully used for years to restore bone continuity. Polydioxanone connects cartilage fragments during the formation of the final supporting tissue (20). When there is no septum cartilage to be employed, it is possible to use polydioxanone plates to place an implant from the auricular cartilage. Polydioxanone plates support the cartilage until the septum is stable, as auricular cartilage is not straight and is not as stable as native nasal septum cartilage (20). Fragments of septum cartilage are sewn together with the absorbable polydioxanone plate after the excision. This allows to create a stable graft that is easy re-insterted in the right place. Polydioxanone plates support the nasal bridge and stabilize the cartilage until the healing process is complete. The degradation of polydioxanone does not interfere with the normal healing process and stimulates the regenerative properties of osseous cells (20). In the literature, there are no reports concerning short- and long-term complications resulting from the use of polydioxanone plates. No allergic reactions, rejection of the polydioxanone plate, local necrosis, or infections have been observed. The results of the procedures have remained satisfactory for many years after surgery (20). Three-layer closure of the perforation with the use of auricular cartilage and two transplants from temporal fascia have been described in patients with perforations smaller than 2 cm. Success was achieved in 86.3% of cases (5). Two patients had to be reoperated and excluded from further analysis. The first patient was HIV-positive. Initially, his clinical outcome was satisfactory, but several months after the procedure, two independent septal perforations occurred. It has been suggested that autoimmune disorders impaired the wound healing process and caused ulceration of the mucous membrane. Another patient, due to the failure of the surgery resulting from non-operative parameters, was also excluded from the final analysis (5).

Another solution is to use bilateral flaps, which allow to include a larger amount of tissue for the closure. The aim of thies technique is to obtain a maximum tissue volume from the inferior and lateral walls of the nasal cavity (21). Bilateral flaps are recommended in patients in whom the perforation size exceeds 15 mm or when closure of the perforation with transerable flaps is not possible. Key elements of the effective perforation closure using bilateral flaps include tension-free closure achieved with harvesting maximal amounts of tissue from the inferior and lateral walls of the nasal cavity in order to provide greater mobility of the flaps, and insertion of obturators when high stress is expected to occur after applying traditional methods (21).

The “cross-stealing” technique has been originally described by Kridel et al. and modified by Mladina et al. (31) Mladina has used this technique in 4 patients with perforations smaller than 2 cm. He achieved complete closure of three perforations and partial closure of one perforation. He used temporal fascia as a transplant. The “cross-stealing” technique has many benefits. The mucosoperichondrial flaps that are used originate from the nasal cavity. There is no need for additional incisions and harvesting flaps from the ethmoid region. In the classical techniques, it is necessary to use flaps that are larger than the perforation. In the “cross-stealing” technique, there is no need for that (7). However, this technique can only be used for anterior perforations. Flap size is limited. Depending on the height of the septum, it may not be possible to use this technique for perforations other than small and medium. Due to the low number of procedures performed using the “cross-stealing” technique, the statistical analysis of the method, possible approaches, and flaps and transplants used are difficult to assess. It is possible that the success rate of this technique will improve with the number of cases and an increase in the surgeons’ experience (7). A new technique of closure of medium-sized perforations consists in using two mucosal flaps harvested from the bottom of the nasal cavity (9).

For perforations smaller than 5 mm, it is most optimal to close them directly, as there is no observed increase in the tension on the closure line. Rotation flaps are most effective in case of anterior perforations that measure less than 2 cm in height. Flaps are useful for perforations maesuring up to 2.5 cm. Large perforations cannot be used with the help of local tissues and it is necessary to use flaps harvested from other regions or transplants (9).Kridel et al. (26) popularized the external approach with harvested flaps and transplants for closure of larger perforations with a 77% success rate (9). Well-vascularized, harvested flaps are resistant, and the risk of necrosis is minimal. The main advantage of this technique is the bilateral closure with independent suture lines, which reduces the risk of surgery failure and postoperative complications. The disadvantages of the technique include its narrow application: the efficacy of the method has been confirmed in perforations measuring up to 1.6 cm (9).

Unilateral harvested mucosal flap can be used for almost every type of septal perforations, regardless of their shape or size. This method consists in using one part of the flap from the bottom and one flap from the top (11). The cross-over flap technique is used for closing medium-sized perforations that are no larger than 2 cm in diameter. It involves creating two flaps: one upper and one lower flap. The flaps cross over the edge of perforation to the opposite nasal cavity (11). It is also possible to use a flap that is supplied by the anterior ethmoid artery. It is a mucosal flap that provides adequate blood supply to the septum thanks to the connection to the artery. This type of flap cannot be used for posterior nasal septum perforations (11). The lower flap from the inferior nasal concha is useful for treatment of perforations of measuring up to 2 cm. The flap is supplied with a posterolateral branch of the nasal artery. In 15% of cases, the inferior nasal concha is also supplied with a branch of the palatine artery. These flaps can be used for treatment of damage to middle ear bones (11). In surgical techniques using middle nasal turbinate, normal airway nasal mucosa is used for reconstructive surgery to restitute nasal anatomy and physiology. Nasal turbinate mucosa is characterized by a good blood supply (11). Using flaps from the lateral wall of the nasal cavity is indicated for medium (1–2 cm) and/or large (2–3 cm) perforations. The blood is supplied to the flaps through the anterior ethmoid artery and facial arteries for anterior flaps, and posterolateral branches of the nasal artery for posterior flaps (11).

Pericranial flap is an innovative technique that can be used to achieve complete closure of septal perforations. The blood is supplied mainly through the deep branches of the supraorbital arteries. This technique may result in a complete reconstruction of the septum in cases in which other methods of treatment have failed (11).

There are some differences concerning treatment of septal perforations in pediatric population (10). The endoscopic approach is possible for the majority of pediatric patients and helps to avoid visible scars. Repairing perforations in small children may be more difficult than repairing the same-sized perforation in adults because of spatial limitations, low availability of mucosal flaps, and problems with post-operative compliance. The availability of neighboring tissues and/or transplants may be limited in small children or in children with large perforations. If septal perforation has been caused by nose picking, this kind of behavior should be strictly prohibited before surgical treatment (10). The patient undergoing surgery should be in an age when they are able to tolerate post-operative care, including nasal plates and nasal hygiene with saline or ointment. Any comorbidities or medications that could affect the wound healing should be taken into account (10). If the child is not qualified for surgical treatment, it is possible to use temporary or permanent obturators. An obturator is installed under general anesthesia. Complications associated with the use of obturators include epistaxis, enlargement of the perforation, crusting, and pain. In case of cartilage separation, cuts in the growth zones and areas responsible for stabilization should be avoided (10). There is no data in the literature concerning the influence of nasal septum perforation closure in children and their future nasal growth. Pediatric literature indicates that unilateral or bilateral mucosal flaps have no adverse effect on the facial growth (10).

Conclusions

Repairing nasal septum perforation is a long-term challange and few surgeons are qualified to perform such procedures.

Anterior perforations have better prognosis than posterior perforations, as they are more easily accessible, moreover, the access to mucosoperichondrial flaps is easier. Large symptomatic perforations may require an individual approach and different sizes of flaps, including transferring tissue from other locations. Data shows that highest success rate is achieved after surgical procedures with the use of mucosal flaps and temporal fascia transplants, as well as acellular human dermal allografts. Possible reasons for failure of surgical procedures include a large perforation with a thin, damaged mucosa, not using a transplant in a perforation that is characterized by excess tissue stress, and poor blood supply of the flap caused by multiple previous operations. In some cases, surgery may be contraindicated due to the patient’s age, general health condition or an underlying pathology. In these cases, nasal obturators can be used as a temporary measure or the final method of treatment. Research on larger groups of patients is needed to increase the safety and efficacy of the procedures for treatment of nasal septum perforations.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Rokkjær MS, Barrett T, Petersen C: Good results after endonasal cartilage closure of nasal septal perforations. Dan Med Bul 2010; 57: A4196.

2. Bochenek A, Reicher M: Anatomia człowieka. 2nd ed., Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL. Warszawa 1989: 30.

3. Krzeski A, Janczewski G (eds.): Choroby nosa i zatok przynosowych. 1st ed., Wydawnictwo Medyczne Sanmedia. Warszawa 1997.

4. Ozturk S, Zor F, Ozturk S et al.: A New Approach to Objective Evaluation of the Success of Nasal Septum Perforation. Arch Plast Surg 2014; 41(4): 403-406.

5. Dayton S, Chhabra N, Houser S: Endonasal septal perforation repair using posterior and inferiorly based mucosal rotation flaps. Am J Otolaryngol 2017; 38(2): 179-182.

6. Sapmaz E, Toplu Y, Somuk BT: A new classification for septal perforation and effects of treatment methods on quality of life. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2018.

7. Islam A, Celik H, Felek SA, Demirci M: Repair of nasal septal perforation with “cross-stealing” technique. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2009; 23(2): 225-228.

8. Mocella S, Muia F, Giacomi PG et al.: Innovative technique for large septal perforation repair and radiological evaluation. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2013; 33(3): 202-214.

9. Raol N, Olson K: A Novel Technique to Repair Moderate-Sized Nasoseptal Perforations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 16: 1-3.

10. Chang DT, Irace AL, Kawai K et al.: Nasal septal perforation in children: Presentation, etiology, and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017; 92: 176-180.

11. Pereira C, Santamaría A, Langdon C et al: Nasoseptal Perforation: from Etiology to Treatment. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2018; 18(1): 5.

12. Giacomini PG, Ferraro S, Di Girolamo S, Ottaviani F: Large nasal septal perforation repair by closed endoscopically assisted approach. Ann Plast Surg 2011; 66(6): 633-636.

13. Mullace M, Gorini E, Sbrocca M et al.: Management of nasal septal perforation using silicone nasal septal button. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2006; 26(4): 216-218.

14. Binar M, Arslan F, Tasli H et al.: An unusual cause of necrosis and nasal septum perforation after septoplasty: Enterobacter cloacae. New Microbes New Infect 2015; 8: 150-153 .

15. Sellin M, Monsen T, Widerström M et al.: Bacterial flora and the epidemiology of staphylococcus aureus in the nose among patients with symptomatic nasal septal perforations. Acta Otolaryngol 2016; 136(6): 620-625.

16. Hulterström AK, Sellin M, Berggren D: The microbial flora in the nasal septum area prone to perforation. APMIS 2012; 20(3): 210-214.

17. Bianchi FA, Gerbino G, Tosco P et al;: Progressive midfacial bone erosion and necrosis: case report and differential diagnosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014; 42(8): 1698-1703.

18. Re M, Paolucci L, Romeo R, Mallardi V: Surgical treatment of nasal septal perforations. Our experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2006; 26(2): 102-109.

19. Krzeski A (ed.): Wykłady z chirurgii nosa. 1st ed., Via Medica. Gdańsk 2005; 117-121.

20. Daneshi A, Mohammadi S, Javadi M, Hassannia F: Repair of large nasal septal perforation with titanium membrane: report of 10 cases. Am J Otolaryngol 2010; 31(5): 387-389.

21. Park JH, Kim Dw, Jin HR: Nasal septal perforation repair using intranasal rotation and advancement flaps. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2013; 27(2): 42-47.

22. Paolucci MRL, Romeo R, Mallardi V: Surgical treatment of nasal septal perforations. Our experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2006; 26: 102-109.

23. Meyer R: Repair techniques in perforations of the nasal septum. Ann Plast Surg Esthet 1992; 37: 154-161.

24. Strelzow VV, Goodman WS: Nasoseptal perforations closureby external rhinoplasty. J Otolaryngol 1978; 7: 43-48.

25. Eviatar A, Myssiorek D: Repair of nasal septal perforation with tragal cartilage and perichondrium grafts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989; 100: 300-302.

26. Kridel RW, Appling WD, Wright WK: Septal perforation closure utilizing the external septorhinoplasty approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986; 112 (2): 168-172.

27. Lee D, Joseph EM, Pontell J, Turk JB: Long-term results of dermal grafting for the repair of nasal septal perforations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 120: 483-486.

28. Bryan TA, Zimmerman J, Rosenthal M, Pribitkin EA:Nasal septal repair with porcine small intestinal submucosa. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003; 5: 528-529.

29. Luff DA, Kam A, Bruce IA, Willatt DJ: Nasal septum buttons: symptom scores and satisfaction. J Laryngol Otol 2002; 116(12): 1001-1004.

30. Sapmaz E, Toplu Y, Somuk BT: A new classification for septal perforation and effects of treatment methods on quality of life. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2018.

31. Mladina R, Heinzel B: “Cross-stealing” technique for septal perforation closure. Rhinology 1995; 33: 174-176.