*Jacek Piłat1, Sławomir Rudzki1, Jacek Bicki2, Wojciech Dąbrowski3

Progress in diagnostic imaging of anal inflammatory diseases

Postępy w diagnostyce obrazowej chorób zapalnych odbytu

11st Chair and Department of General Surgery, Transplantation and Nutritional Therapy, Medical University of Lublin

2Institute of Medical Sciences of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce

3Chair and 1st Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, Medical University of Lublin

Streszczenie

Autorzy przedstawiają zagadnienia z zakresu diagnostyki najczęściej spotykanych chorób zapalnych odbytu. W sposób szczególny zajmują się przetokami i ropniami odbytu. Przedstawiają różne metody diagnostyczne: począwszy od podstawowego badania proktologicznego poprzez metody instrumentalne. Oceniają przydatność, wady i ograniczenia poszczególnych metod. Najwyższą ocenę z przedstawionych metod diagnostycznych uzyskały dwa badania, tj. rezonans magnetyczny i badanie endosonograficzne w opcji 3D, wsparte użyciem opcji render mode lub wody utlenionej jako środka kontrastowego. Oba badania w pewnym sensie są porównywalne, jeżeli chodzi o choroby zapalne odbytu. W przypadku badania endosonograficznego zaletami są: niski koszt, powtarzalność i dostępność. Do wad rezonansu magnetycznego należą: wysoka cena badania, mała dostępność i ewentualna klaustrofobia pacjenta lub obecność metalowych implantów. Jednak niezaprzeczalną zaletą badania metodą rezonansu magnetycznego jest możliwość oceny przetok lub ropni odbytu zlokalizowanych wysoko, powyżej mięśni dźwigaczy. W ocenie zmian głęboko położonych przewaga rezonansu magnetycznego wynika z krótszego ogniska sondy endosonograficznej. Wysoka częstotliwość sondy daje dobrą jakość obrazu, ale okupiona jest krótszą penetracją w głąb promieni ultrasonograficznych. Użycie opcji render mode lub kontrastu – wody utlenionej – stawia badanie endosonograficzne w jednym rzędzie z rezonansem magnetycznym w diagnostyce płycej położonych, częściej występujących przetok i ropni. Mając na uwadze niższe koszty i powtarzalność badania endosonograficznego, jest ono cennym nowoczesnym instrumentem w diagnostyce zmian zapalnych odbytu.

Summary

The authors present issues related to the diagnosis of the most common inflammatory diseases of the anus. They deal with anal fistulas and abscesses in a special way. They present various diagnostic methods: from basic proctological examination to instrumental methods. They asses the usefulness, disadvantages and limitations of individual methods. The highest assessment of the presented diagnostic methods was obtained by two tests, i.e. magnetic resonance imaging and endosonographic examination in the 3D option, supported by the use of the render mode option or hydrogen peroxide as a contrast agent. In a sense, both examinations are comparable when it comes to inflammatory diseases of the anus. For endosonographic examination, the advantage is low cost, repeatability and availability. The disadvantage of magnetic resonance imaging is the high price of the test, the low availability and possible claustrophobia of the patient or the presence of metal implants. However, the undeniable advantage of magnetic resonance imaging is the ability to assess anal fistulas or abscesses located high above the levator muscles. In the assessment of deeply located lesions, the advantage of magnetic resonance results from the shorter focus of the endosonographic probe. The high frequency of the probe gives good image quality, but it is paid for the shorter penetration of the ultrasound rays. The use of the render mode or contrast – hydrogen peroxide option puts the endosonographic examination in a one row with magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of the most frequent occurring fistulas and abscesses. Considering lower costs, repeatability of the endosonographic examination it is a valuable modern instrument in the diagnosis of inflammatory lesions of the anus.

Inflammatory diseases of the anus are one of most common causes of patients’ appointments at surgical clinics and wards. Inflammatory diseases include abscess, fistula, anal fissure, and proctitis. They are manifested by various signs and symptoms, mainly local ones (pain, redness, oedema, bleeding, bowel movement disorders, discharge of purulent or bloody contents within the anus) and sometimes general ones, i.e. inflammatory, e.g. for highly located abscesses. Appropriate diagnostics is important for the correct diagnosis and optimization of therapy.

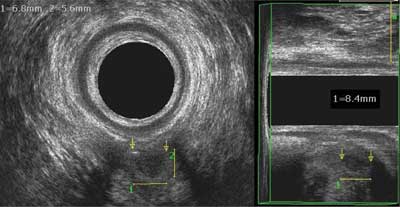

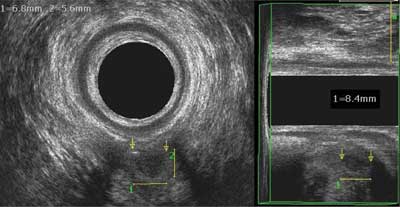

The most common inflammatory diseases of the anus are anal fissures, fistulas and abscesses, which, besides basic proctological examination, often need additional imaging tests. The result of such an examination is to determine the course of the fistula canal or the abscess location (relation to sphincters), or to determine internal opening location. Anal abscesses are generally clinically manifested and the diagnosis does not raise any doubts. However, there are hourglass-shaped abscesses or abscesses located high above the levator ani muscles, which may not demonstrate any symptoms in the anal area, but general symptoms only. In these cases, extended diagnostics with additional tests is very important for the appropriate treatment. Pain in the anus area of unclear etiology is also an indication for expanded diagnosis, as basic proctological examination is not sufficient (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A small abscess with evident air, deeply located between the pubic-rectal muscle brachium; clinically silent abscess between the arrows, with a size of 8.4 x 6.8 x 5.6 mm

Patients often visit medical facilities due to complications or recurrence of proctological diseases. Proper diagnosis and evaluation of already occurring damages caused by the disease and the treatment process affect the therapy and final result. Encopresis may be caused by systemic diseases, aging, but also by sphincter failure due to e.g. past procedures, anal canal injury.

Diagnosis of proctological diseases is based on a history and physical examination as well as additional tests. In addition to examining the perineum and perianal area and finger examination of the anus, the following examinations may be carried out: anoscopy or rectoscopy, transrectal or perrotal endosonography, defecography, balloon excretion test, fistulography, rectal-anal manometry, CT and magnetic MRI with or without rectal coil. All of these examinations have their advantages and limitations, the selection depends on the history and initial proctological examination, and the availability of the diagnostic method.

An anal fistula is a granulation tissue surrounding canal that connects the internal fistula opening located in the anal canal with the external opening – most commonly located on the skin around the anus area. According to the cryptic theory, infection that begins in Herman’s anal glands and spreads to the perianal area is the cause of abscesses and fistulas in this area. Acute infection forms an abscess, and a fistula is its chronic form (1, 2).

Other less frequent etiological factors include: inflammatory diseases (Crohn’s disease in particular, where the internal opening is often located deeper than in the perianal crypts), infection spreading from anal fissure, coccygeal cysts, tumors, foreign bodies, lymphomas, tuberculosis, HIV infection, post procedure complications in this area (3, 4).

The purpose of fistula diagnostics is to properly classify, i.e. describe, the fistula anatomical course. Currently, the Parks classification is the most commonly used one. This classification considers location of the internal opening and the course of the fistula canal in relation to the external sphincter muscle. The following fistulas are distinguished: submucous, inter-sphincteric, trans-sphincteric, supra-sphincteric and extra-sphincteric (5).

It is also important to determine whether the fistula transits the anterior or posterior or lateral part of the anal canal. This is particularly important in women where the anterior – perineal part of the anal canal has a shorter external sphincter and therefore fistula surgery in the anterior part is more exposed to complication in the form of sphincter failure (6, 7).

Goodsall and Miles classification is another classification that divides fistulas into: complete, i.e. of two openings – external opening on the skin around the anus, and internal opening to the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract, and incomplete, i.e. externally blind fistula, i.e. no external opening or internally blind fistula, i.e. without visible internal opening (8).

Many additional tests may be used in the diagnostics of anal fistulas, however there are practitioners who believe that basic physical examination is sufficient. This particularly refers to primary fistulas, untreated and uncomplicated. In other cases, additional tests should be performed (9).

The Salomon Goodsall’s rule is the first clue, although not very precise, as to the location of the internal opening when inspecting the perianal area. It divides the anus by means of a horizontal line to anterior and posterior parts. The location of the external opening in the anterior half suggests a suspected fistula with a straight canal going to the anterior crypt. If the external opening is in the posterior half, or more than 3 cm from the anus edge in the anterior half, then the fistula canal most likely goes to the posterior crypt – caudal. This rule works in circa. 80% of cases of fistulas with an internal opening in the posterior half, and only in circa. 50% of cases with an opening in the anterior half of a divided anus (10).

The most frequently performed additional tests in the diagnostics of anal fistulas include (11):

1. X-ray fistulography – rarely used currently due to the need to irradiate a patient and low accuracy, i.e. up to 25% in identification of internal opening in the appropriate crypt. Locating the internal opening in high extrasphincteric fistulas is its advantage – this allows, for example, for the contrast to enter the sigmoid diverticulum (12, 13).

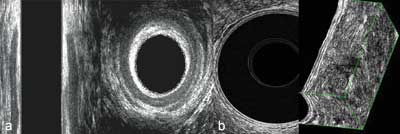

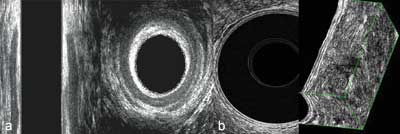

2. Transanal and transrectal ultrasonography (TAUS – transanal ultrasound and TRUS – transrectal ultrasound) – used due to high accuracy and examination specificity as well as low cost and repeatability. The test is performed in the Sims position (i.e. on the left side), a high-frequency ultrasound probe (from 9 to 16 MHz) is introduced, ensuring a 360-degree image – which allows for entire anus view on the image. When examining the rectal ampulla (a water balloon should be used to ensure conduction of the ultrasound beam), a layered structure of a rectal wall may be viewed and analyzed and compared with an image of the entire cross-section (fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2a, b. (a) Anal canal examination (hypoechogenic internal sphincter and surrounding external sphincter showing mixed echogenicity); (b) rectal ampulla examination (visible layered intestinal wall structure)

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

29 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

69 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

129 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 78 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Limura E, Giordano P: Modern management of anal fistula. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 12-20.

2. Arendt J, Trompeta J, Michalski P et al.: Ropień okołoodbytniczy – problemy rozpoznawcze i lecznicze. Chirurgia Polska 2000; 2: 91-101.

3. Practice parameters for treatment of fistula-in-ano. The Standards Practice Task Force. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 1361-1362.

4. Rosen L: Anorectal abscess-fistulae. Surg Clin North Am 1994; 74: 1293-1308.

5. Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD: A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976; 63: 1-12.

6. Buchanan GN, Bartram CI, Williams AB et al.: Value of hydrogen peroxide enhancement of three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound in fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 141-147.

7. Roig JV, Jordán J, García-Armengol J et al.: Changes in anorectal morphologic and functional parameters after fistula-in-ano surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1462-1469.

8. Goodsall DH, Miles WE: Anorectal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 1982; 25: 262-278.

9. Sloots CE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Poen AC, Cuesta MA: Assessment and classification of never operated and recurrent cryptoglandular fistulas-in-ano using hydrogen peroxide enhanced transanal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis 2001; 3: 422-426.

10. Cirocco WC, Reilly JC: Challenging the predictive accuracy of Goodsall’s rule for anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 1992; 35: 537-542.

11. Bartram C, Buchanan G: Imaging anal fistula. Radiol Clin North Am 2003; 41: 443-457.

12. Amato A, Bottini C, De Nardi P et al.: Evaluation and management of perianal abscess and anal fistula: a consensus statement developed by the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR). Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19: 595-606.

13. Bitter K, Bitterová J, Lohnert J et al.: Fistulografia perianálnych fistúl ako determinujúci faktor operacnej stratègie. ?s Radiol 1985; 29: 374-377.

14. Santoro GA, Fortling B: The advantages of volume rendering in three-dimensional endosonography of the anorectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 359-368.

15. Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kołodziejczak M, Szopiński TR: The accuracy of a postprocessing technique – volume render mode – in three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography of anal abscesses and fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 238-244.

16. Visscher AP, Schuur D, Slooff RA et al.: Predictive factors for recurrence of cryptoglandular fistulae characterized by preoperative three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis 2016; 18(5): 503-509.

17. Cheong DM, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD, Jagelman DG: Anal endosonography for recurrent anal fistulas: image enhancement with hydrogen peroxide. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 1158-1160.

18. Kruskal JB, Kane RA, Morrin MM: Peroxide-enhanced anal endosonography: technique, image interpretation, and clinical applications. Radiographics 2001; 21 (Spec No): S173-189.

19. Oliveira IS, Kilcoyne A, Price MC, Harisinghani M: MRI features of perianal fistulas: is there a difference between Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s patients? Abdom Radiol (New York) 2017; 42: 1162-1168.

20. Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, Stoker J: A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut 2014; 63(9): 1381-1392.

21. Sudoł-Szopińska I, Jakubowski W: Endosonography of anal canal diseases. Ultrasound Q 2002; 18: 13-33.

22. Zbar AP, Oyetunji RO, Gill R: Transperineal versus hydrogen peroxide-enhanced endoanal ultrasonography in never operated and recurrent cryptogenic fistula-in-ano: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol 2006; 10: 297-302.

23. Terracciano F, Scalisi G, Bossa F et al.: Transperineal ultrasonography: First level exam in IBD patients with perianal disease. Dig Liver Dis 2016; 48: 874-879.

24. Plaikner M, Loizides A, Peer S et al.: Transperineal ultrasonography as a complementary diagnostic tool in identifying acute perianal sepsis. Tech Coloproctol 2014; 18(2): 165-171.

25. Kołodziejczak M, Santoro GA, Słapa RZ et al.: Usefulness of 3D transperineal ultrasound in severe stenosis of the anal canal: preliminary experience in four cases. Tech Coloproctol 2014; 18: 495-501.

26. Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI et al.: Clinical Examination, Endosonography, and MR Imaging in Preoperative Assessment of Fistula in Ano: Comparison with Outcome-based Reference Standard. Radiology 2004; 233: 674-681.

27. Burdan F, Sudol-Szopinska I, Staroslawska E et al.: Magnetic resonance imaging and endorectal ultrasound for diagnosis of rectal lesions. Eur J Med Res 2015; 20: 4.

28. Dohan A, Eveno C, Oprea R et al.: Diffusion-weighted MR imaging for the diagnosis of abscess complicating fistula-in-ano: preliminary experience. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 2906-2915.

29. Cattapan K, Chulroek T, Kordbacheh H et al.: Contrast-vs. non-contrast enhanced MRdata sets for characterization of perianal fistulas. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019; 44(2): 446-455.

30. Waniczek D, Adamczyk T, Arendt J, Kluczewska E: Direct MRI fistulography with hydrogen peroxide in patients with recurrent perianal fistulas: a new proposal of extended diagnostics. Med Sci Monit 2015; 21: 439-445.

31. Bhatt S, Jain BK, Singh VK: Multi Detector Computed Tomography Fistulography In Patients of Fistula-in-Ano: An Imaging Collage. Polish J Radiol 2017; 82: 516-523.

32. Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL, van der Hoop AG et al.: Preoperative MR imaging of anal fistulas: Does it really help the surgeon? Radiology 2001; 218: 75-84.

33. Liang C, Lu Y, Zhao B et al.: Imaging of anal fistulas: comparison of computed tomographic fistulography and magnetic resonance imaging. Korean J Radiol 2014; 15(6): 712-723.

34. Liang C, Jiang W, Zhao B et al.: CT imaging with fistulography for perianal fistula: does it really help the surgeon? Clin Imaging 2013; 37: 1069-1076.

35. Meinero P, Mori L: Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT): a novel sphincter-saving procedure for treating complex anal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol 2011; 15: 417-422.

36. Schwandner O: Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) combined with advancement flap repair in Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol 2013; 17: 221-225.

37. Wałęga P, Romaniszyn M, Nowak W: VAAFT: a new minimally invasive method in the diagnostics and treatment of anal fistulas – initial results. Pol Przegl Chir 2014; 86(1): 7-10.

38. Rezaie A, Iriana S, Pimentel M et al.: Can three-dimensional high-resolution anorectal manometry detect anal sphincter defects in patients with faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: 468-475.

39. Cerro CR, Franco EM, Santoro GA et al.: Residual defects after repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries and pelvic floor muscle strength are related to anal incontinence symptoms. Int Urogynecol J 2017; 28: 455-460.

40. Felt-Bersma RJF, Vlietstra MS, Vollebregt PF et al.: 3D high-resolution anorectal manometry in patients with perianal fistulas: comparison with 3D-anal ultrasound. BMC Gastroenterol 2018; 18: 44.

41. Siddiqui MRS, Ashrafian H, Tozer P et al.: A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of endoanal ultrasound and MRI for perianal fistula assessment. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 576-585.

42. Karanikas I, Koutserimpas C, Siaperas P et al.: Transrectal ultrasonography of perianal fistulas: a single center experience from a surgeon’s point of view. G Chir 2018; 39(4): 258-260.

43. Mihmanli I, Kantarci F, Dogra VS: Endoanorectal ultrasonography. Ultrasound Q 2011; 27: 87-104.

44. Navarro-Luna A, García-Domingo MI, Rius-Macías J, Marco-Molina C: Ultrasound study of anal fistulas with hydrogen peroxide enhancement. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 108-114.

45. Sudoł-Szopińska I, Jakubowski W, Szczepkowski M: Contrast-enhanced endosonography for the diagnosis of anal and anovaginal fistulas. J Clin Ultrasound 2002; 30: 145-150.

46. Knoefel WT, Hosch SB, Hoyer B, Izbicki JR: The Initial Approach to Anorectal Abscesses: Fistulotomy Is Safe and Reduces the Chance of Recurrences. Dig Surg 2000; 17: 274-278.

47. Alabiso ME, Iasiello F, Pellino G et al.: 3D-EAUS and MRI in the Activity of Anal Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016; 2016: 1895694.

48. Garcès-Albir M, García-Botello SA, Espi A et al.: Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound for diagnosis of perianal fistulas: Reliable and objective technique. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8: 513-520.

49. Visscher AP, Felt-Bersma RJ: Endoanal Ultrasound in Perianal Fistulae and Abscesses. Ultrasound Q 2015; 31: 130-137.

50. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A et al.: Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2016; 30: 33-44.

51. Sun MRM, Smith MP, Kane RA: Current techniques in imaging of fistula in ano: three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2008; 29: 454-471.