© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 2/2010, s. 141-146

Rafał Kamiński2, Cezary Walczyński1, Maciej Makowski1, Bogumił Leszczyński1, Andrzej Suwara1, Marcin Wąsowski1, Waldemar Rylski1, *Stanisław Pomianowski1

Intramedullary nail fixation of intertrochanteric fractures

Leczenie złamań przezkrętarzowych kości udowej metodą osteosyntezy śródszpikowej

1Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, the Medical Centre of Postgraduate Education,

Professor Adam Gruca Hospital in Otwock

Head of the Department: prof. Stanisław Pomianowski, M.D., Ph.D.

2Rafał Kamiński is a recepient of scholarship founded by Prof. Jakub Gołąb from the Foundation for Polish Science „Mistrz” programme

Streszczenie

Złamanie przezkrętarzowe dotyczy bliższego końca kości udowej. Dominują one u osób w wieku podeszłym, są wynikiem najczęściej urazu niskoenergetycznego i najczęściej zdarzają się u kobiet. Warto wspomnieć, iż obecnie wystąpienie tego typu złamania jest kryterium rozpoznania osteoporozy u pacjenta. Złamania te występują również u osób młodych, ale w tym przypadku są następstwem urazów wysokoenergetycznych i najczęściej wiążą się z urazem wielomiejscowym lub wielonarządowym. Wśród pacjentów w wieku podeszłym, złamanie przezkrętarzowe, ze względu na rokowanie, zwane przez wiele lat było „ostatnim złamaniem w życiu”. Postęp wiedzy medycznej (choroby wewnętrzne, anestezjologia i intensywna terapia), technologii medycznej oraz techniki chirurgicznej pozwala obecnie skutecznie leczyć tego typu złamania oraz daje pacjentowi szansę na powrót do wcześniejszej aktywności fizycznej. Pomimo tego, śmiertelność chorych zaopatrzonych w poprawny sposób nadal sięga 30% w pierwszym roku po wystąpieniu incydentu. Z uwagi na wiek pacjentów oraz współistniejące choroby internistyczne, wystąpienie powikłań nie jest rzadkie i obejmuje powikłania internistyczne, jak i chirurgiczne. W naszej Klinice średnio rocznie hospitalizujemy około 220 pacjentów ze złamaniem przezkrętarzowym. Praktycznie wszyscy pacjenci leczeni są we wczesnych dobach po przyjęciu i zaopatrywani są gwoździem śródszpikowym typu gamma. W artykule przedstawiono sposoby leczenia złamań przezkrętarzowych, skupiając się na metodzie śródszpikowej oraz porównując ją z innymi metodami zaopatrywania tego typu złamań. Zanalizujemy również występujące powikłania.

Summary

Intertrochnateric fractures are located in the proximal femur. They dominate in elderly, are result of low-energy trauma and most frequently may happen among women. Noteworthy, intertrochanteric is a criterion of osteoporosis. Such fractures may happen in young individuals, but are result of high-energy trauma and usually are a part of polytrauma. Based on the survival rates, for many years trochanteric fractures were called "last fractures in life”. The advances in medical sciences (namely: medicine, anesthesia and critical care), medial engineering and surgical techniques are offering opportunities to successfully treat this type of fracture. They also give possibilities for quicker recovery and return to pre-fracture activity level. Despite the progress the mortality rate in the first year after incidence is still high and averages about 30%. Additionally, considering the age of patients and comorbidities the complications are not uncommon. In our clinic we treat on average 220 patients with intertrochanteric fracture. Almost all patients are treated within first few days after admission and fracture fixation is performed with gamma nail. In our article we presented the intramedullary nail fixation for trochanteric fractures. We focused on intramedullary nail fixation and we compared this method with other types of fixation. We also analyze complications.

Introduction

Trochanteric fractures are located extracapsularly, in the proximal part of the femur, and may extend up to 5 cm down the minor trochanter (1). This type of fractures dominates in the elderly and is caused by low energy trauma (direct lateral trauma). In this group of patients trochanteric fractures may also be the result of neoplastic disease with metastases to proximal femur. The female to male ratio is 2-8:1.

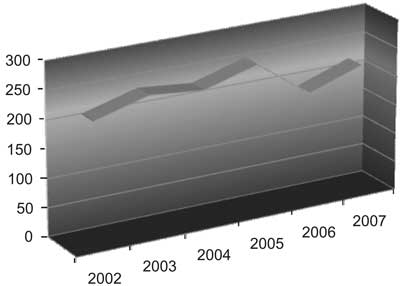

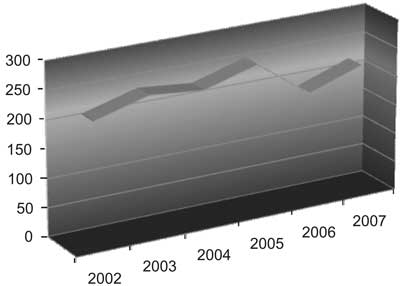

In case of younger patients, trochanteric fractures result from high-energy trauma, direct lateral force (motor vehicle accident) or axial loading (fall from the height or MVA). The morbidity is estimated at 85/100 000/year. In our Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology we deal with 180 to 248 cases a year (fig. 1). Interestingly, even though not the most frequent, the treatment of trochanteric fractures costs more than other fractures all together. The costs are estimated around $8 billion/year in U.S.A. Usually, this type of fractures is accompanied by distal radius fractures, proximal humerus fractures, rib fracture or lumbar spine fracture. Still, despite optimal treatment the yearly mortality spikes as high as 30% in the first years after the event.

Fig. 1. Total number of trochanteric region fractures treated in the Department during 2002-2007 period (total amount of more than 1400 during 7 years – including 2008).

Classification

There are several types of classifications regarding fractures of the trochanteric region: historically it was Griffin and Boyd or Evans classifications, currently the most widely accepted is AO classification. The fractures of the trochanteric region are divided into 3 groups.

A1: Simple (2-fragment) peri-trochanteric area fractures (24-month survival: 50.4% male, 84.9% female)

A1.1 Fractures along the intertrochanteric line

A1.2 Fractures through the greater trochanter

A1.3 Fractures below the minor trochanter

A2: Multifragmentary peri-trochanteric fractures (24-month survival: 92.7% male, 66.5% female)

A2.1 With one intermediate fragment (minor trochanter detachment)

A2.2 With 2 intermediate fragments

A2.3 With more than 2 intermediate fragments

A3: Intertrochanteric fractures (24-month survival: 92.3% male, 67.9% female)

A3.1 Simple, oblique

A3.2 Simple, transverse

A3.3 With a medial fragment

Additionally we could distinguish:

• Multifragmentary and multilevel fractures.

• Reverse trochanteric fractures or transverse fractures.

Diagnosis

Setting clinical diagnosis usually requires:

• physical examination,

• pelvic X-ray AP, axial x-ray of the hip, sometimes traction x-ray is required,

• in selected cases for proper diagnosis CT scanning, MRI imaging or scyntygraphy is required,

• CBC, electrolytes, liver tests, glucose, CRP, chest x-ray and ECG.

Differential diagnosis should include:

• Femoral neck fractures.

• Acetabular fractures.

• Exacerbation of osteoarthritis of the hip.

• Acute osteomyelitis.

Treatment

First attempt of surgical treatment was carried in 1850 by Langenbeck. He used a "blind” method (without fluoroscopy) with intramedullary nail introduced from trochanteric site. There were followers but surgical technique and lack of antibiotics were major causes of poor outcome (3). As a result in XIX century, conservative treatment was a method of choice. Trochanteric fractures were treated with resting, traction or prolong hip casting. The nonunion was not considered a problem at that time. Prolonged rest time and associated complications (pulmonary embolism, pulmonary infections, venous thrombosis, bedsores, nonunion, malunion or inability to restore previous physical activity) compelled surgeons to look for more promising treatment methods. As medical technology was advancing, in XX century surgical treatment became a method of choice.

Ideally, the surgical procedure is performed within 12 hours of admission. In case of patients with severe co-morbidities, requiring biochemical supplementation or general medical review, the surgery should not be delayed more than 48 h from admission. The only contraindications for surgical treatment are uncorrectable medical conditions, as coagulatory or metabolic defects, which carry higher risk of death.

Surgical methods in the treatment of trochanteric fractures

Considering biomechanics and anatomy of the fracture (distal fragment is externally rotated, in adduction and varus and proximal part in abduction) the reduction of the fracture should be performed on operation table by axial traction, abduction and internal rotation (4).

In the treatment of fractures of the trochanteric region several methods have been employed: Ender's nails, angular plate, ZESPOL, external stabilization.

Currently, there are 2 methods widely used (fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Patinet (W.L) with new trochanteric fracture on L side (several years between surgeries). Fixed with DHS (right) and intramedullary nail (left).

• DHS (Dynamic Hip Screw).

• Intramedullary nailing (gamma type).

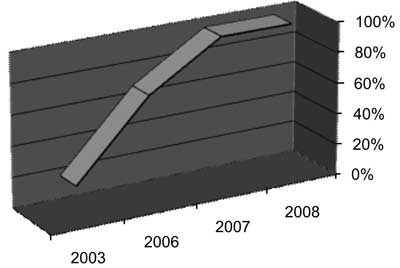

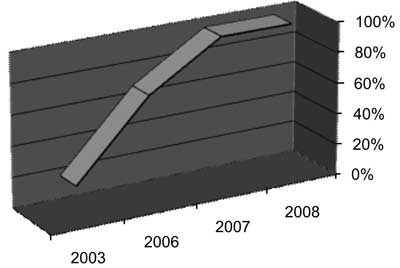

In our Department intramedullary nailing is the predominant method (fig. 3). It was introduced into our practice in 1995. It has several advantages, which in our opinion make it the method no. 1:

Fig. 3. Average percentage of intramedullary nail fixation for trochanteric region fractures in the Deparmtment.

• smaller incision, which causes:

– lower tissue damage (5),

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

29 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

69 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

129 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 78 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Netter FN: Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations. Ciba Pharmaceutical Co1987.

2. Horesh Z, Keren Y, Msika C et al.: Unstable intertrochanteric fractures: our experience with sliding hip screw. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – British Volume 2008; 90-B, Suppl III: 507.

3. Knothe L, Knothe Tathe ML, Perren SM: 300 Years of Intramedullary Fixation – from Aztec Practice to Standard Treatment Modality. European Journal of Trauma 2000; 26: 217-225.

4. Tylman D, Dziak A (Red.): Traumatologia narządu ruchu, t. 1-2. PZWL 2008:

5. Radford PJ, Needoff M, Webb JK: A prospective randomised comparison of the dynamic hip screw and the gamma locking nail. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75: 789-93.

6. Saudan M, Lübbeke A, Sadowski C et al.: Pertrochanteric fractures: is there an advantage to an intramedullary nail? A randomized, prospective study of 206 patients comparing the dynamic hip screw and proximal femoral nail. J Orthop Trauma 2002; 16: 386-93.

7. Pakuts AJ: Unstable subtrochanteric fractures-gamma nail versus dynamic condylar screw. Int Orthop 2004; 28: 21-4.

8. Hardy DC, Descamps P, Krallis P et al.: Use of an intramedullary hip-screw compared with a compression hip-screw with a plate for intertrochanteric femoral fractures. A prospective, randomized study of one hundred patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80: 618-30.

9. Baumgaertner MR: The pertrochanteric external fixator reduced pain, hospital stay, and mechanical complications in comparison with the sliding hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A: 1488.

10. Ahrengart L, Törnkvist H, Fornander P et al.: A randomized study of the compression hip screw and Gamma nail in 426 fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 401: 209-22.

11. Adams CI, Robinson CM, Court-Brown C et al.: Prospective randomized controlled trial of an intramedullary nail versus dynamic screw and plate for intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. J Orthop Trauma 2001; 15: 394-400.

12. Koval KJ, Sala DA, Kummer FJ et al.: Postoperative weight-bearing after a fracture of the femoral neck or an intertrochanteric fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80: 352-6.

13. Sadowski C, Lübbeke A, Saudan M et al.: Treatment of reverse oblique and transverse intertrochanteric fractures with use of an intramedullary nail or a 95 degrees screw-plate: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A: 372-81.

14. Lichtblau S: The unstable intertrochanteric hip fracture. Orthopedics 2008; 31: 792-797.

15. Suckel AA, Dietz K, Wuelker N et al.: Evaluation of complications of three different types of proximal extra-articular femur fractures: differences in complications, age, sex and surviving rates. Int Orthop 2007; 31: 689-695.

16. Ahrengart L, Tornkvist H, Fornander P et al.: Gamma nail vs. compression hip screw for trochanteric fractures – complications and patient outcome. Acta Orthop Scand 1995; 66, Suppl 265: 23.