Michał Michalik1, *Adrianna Podbielska-Kubera1, Maria Pawłowska2, Jolanta Miazga2

Bacterial flora in chronic sinusitis in children

Flora bakteryjna w przewlekłym zapaleniu zatok u dzieci

1Department of Otolaryngology, MML Medical Centre, Warsaw, Poland

Head of Department: Michał Michalik, MD, PhD

2„Diagnostyka”, Central Laboratory, Warsaw, Poland

Head of Department: Maria Pawłowska, Director of the Region

Streszczenie

Przewlekłe zapalenie błony śluzowej nosa i zatok to jedna z głównych przyczyn zachorowalności w populacji pediatrycznej. Etiologia przewlekłego zapalenia zatok (PZZ) pozostaje nadal w sferze badań. Większość przypadków PZZ rozwija się na bazie niewyleczonego ostrego zapalenia zatok. W ostrym zapaleniu zatok mamy najczęściej do czynienia z jednym gatunkiem bakterii, zwykle tlenowych. W PZZ dominuje flora bakteryjna mieszana, z obecnością 2-3 szczepów bakteryjnych. Najczęstszymi patogenami są: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, S. aureus, koagulazo-ujemne gronkowce, a także bakterie Gram-ujemne: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Escherichia coli i bakterie beztlenowe.

W badanej grupie pacjentów przeważały gronkowce: wyizolowano 36 szczepów S. aureus i 31 szczepów S. epidermidis. Typowe patogeny dróg oddechowych były praktycznie nieobecne, stanowiły tylko niewielki procent wszystkich izolowanych drobnoustrojów.

Pełna diagnostyka i leczenie chorych z PZZ powinny obejmować konsultacje laryngologiczne, mikrobiologiczne, alergologiczne, biochemiczne, histopatologiczne, a także diagnostykę obrazową. Bardzo ważna jest izolacja materiałów o wysokiej wartości diagnostycznej (aspiraty, tkanki). Dobór właściwej antybiotykoterapii, poza określeniem antybiotykooporności bakterii, może wymagać oznaczenia cech wirulencji wyhodowanych szczepów.

Summary

Chronic rhinosinusitis is one of the main causes of morbidity in the paediatric population. The aetiology of chronic sinusitis (CS) is still investigated. Most cases of chronic sinusitis develop from unresolved acute sinusitis. Acute sinusitis is usually associated with one species of bacteria (most often aerobic), whereas chronic sinusitis is dominated by a mixed bacterial flora including 2-3 bacterial strains. The most common pathogens in chronic sinusitis are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, S. aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, as well as Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Escherichia coli and anaerobic bacteria.

Staphylococci predominated in the study group of patients: 36 strains of S. aureus and 31 strains of S. epidermidis were isolated. Typical respiratory pathogens were practically absent, and constituted only a small percentage of all isolated microorganisms.

Full diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic sinusitis should include laryngological, microbiological, allergological, biochemical, and histopathological consultations as well as diagnostic imaging. Isolation of materials with high diagnostic value (aspirates, tissues) is very important. The selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy, in addition to assessing bacterial resistance to antibiotics, may require the determination of virulence traits of cultured strains.

Characteristics of chronic sinusitis

Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are considered to be one of the most common reasons for children’s visits to outpatient clinics in the United States. They generate billions in medical expenses, mainly as a result of school absence and lost days of work in the case of parents attending to their ill children. Literature data indicate 6-8 upper respiratory viral infections in children annually. These infections may be complicated by acute otitis media (AOM) and paranasal sinusitis (1, 2).

Depending on disease duration, symptoms and aetiological factors, acute and chronic sinusitis may be distinguished. Acute sinusitis is characterised by symptoms persisting for up to 4 weeks. In the case of chronic sinusitis (CS), the symptoms persist for more than 12 weeks. Patients with symptoms persisting for 4-12 weeks are diagnosed with subacute sinusitis (2). Sinusitis may be also classified as related to nasal polyps (eosinophilic inflammation) and unrelated to polyps (neutrophilic inflammation) (3).

Chronic rhinosinusitis is the main cause of morbidity in the paediatric population (4). It is difficult to determine the incidence of the disease in children, however, it is estimated that 5-10% of children with UTIs will develop acute rhinosinusitis, which often becomes chronic (6). The maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses, which are already present at birth, are most often affected in small children. Other sinuses are affected at a later stage. The sphenoidal sinuses form at the age of 3 years, while the frontal sinuses develop at the age of about 7 years. Full pneumatisation of maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses is observed in 12-year--old children (2).

CS is diagnosed based on subjective symptoms, their duration, and objective evidence for inflammation (5). The main symptoms of CS include nasal mucosal congestion, abundant discharge, nasal obstruction, reduced sense of smell, and malaise (6). Chronic sinusitis most often evolves in stages, with various pathological processes, different bacteriology and various forms of treatment at each stage. Over time, the disease process becomes more complex, difficult to treat and more likely to relapse (7).

The aetiopathology of CS

The sinuses are lined with a mucous membrane producing large amounts of mucus. The mucosa contains ciliary epithelium covered with cilia. Pendular movement of cilia facilitates the release of secretions from the sinuses. Recurrent infections contribute to oedema of the nasal and sinus mucosa. Mucosal oedema leads to mucociliary dysfunction. The connection between sinuses and nasal cavity becomes narrowed or completely closed (8).

Deviated nasal septum and hypertrophied nasal turbinates promote infection and make the treatment difficult. Patients with these anatomical defects are at particular risk of an impaired outflow of sinus secretions. The secretion may contain contaminants from the nasal vestibule or nasopharyngeal bacterial flora (1).

CS has a multifactorial aetiology and may be associated with mucociliary dysfunction, immune disorders, allergy, environmental or social factors, gastro-oesophageal disorders, reflux disease, and chronic bacterial infection (4). Furthermore, chronic sinusitis may be caused by nasal polyps, nasal septum deviation, facial injury, respiratory infections, cystic fibrosis, HIV, and exposure to environmental pollutants (6, 9).

Age is a risk factor for chronic sinusitis. The risk of infection is 74% for 2-6-year-old children and 38% for children aged > 10 years (3).

Overlapping symptoms of various URTIs make the diagnosis complicated. Chronic rhinosinusitis, IRTIs, tonsillar hyperplasia, tonsillitis and even exacerbated allergic rhinitis should be considered in the diagnosis. The pathophysiological role of tonsils in chronic rhinosinusitis is associated with their anatomical location, close to the nasal cavity. Tonsils are a reservoir of bacteria, creating optimal conditions for both onset and persistence of chronic paranasal sinusitis in children (3).

Multidisciplinary teams are formed to determine the epidemiology, pathophysiology and diagnostic/therapeutic methods for CS in adults. Chronic sinusitis in children differs from that in adults; therefore, studies to develop treatment guidelines for CS in the paediatric population are needed (6). It is postulated by most physicians that microorganisms play a crucial role in the aetiology of most CS cases (1).

Microbiology of CS

Chronic paranasal sinusitis may be caused by bacteria, viruses and fungi (2). It was thought for a long time that healthy individuals have sterile sinuses. However, research showed that bacterial colonies are present not only in patients with CS, but also in healthy controls (10). The relationship between bacterial microflora and sinusitis is still investigated.

While it is agreed in literature that bacteria are an aetiological factor in acute sinusitis, no consensus was reached on the role of bacteria in chronic sinusitis (1). Microbiology of paranasal sinusitis is related to different stages of the disease. The early phase (acute rhinosinusitis) is usually caused by viral infection (rhinovirus, adenovirus, influenza or parainfluenza virus). Viral infections usually last up to 10 days. Some of the patients develop secondary bacterial infection (1). One bacterial species (usually aerobic) dominates in acute sinusitis in most patients (10). Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common bacterial pathogens (1, 11).

For CS, mixed bacterial flora comprising 2-3 strains is dominant (10). Microbiological findings indicate the presence of gram-positive aerobic bacteria, such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenza, M. catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, β-haemolytic streptococci and anaerobic bacteria (of the genus Bacteroides, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium) in CS (3).

Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), can colonise nasal mucosa and is more prevalent in CS patients compared to healthy population. MRSA isolation rates have increased over the past decade, accounting for more than 2/3 of S. aureus isolates (1). S. aureus strains are considered the main causative organism in chronic sinusitis. Children with isolated MRSA are more likely to develop recurrent sinusitis compared to children with methicillin-sensitive S. aureus strains. However, no statistical differences were found (11). The nasal cavity is also colonised by Staphylococcus epidermidis; however its pathogenicity in CS is still under investigation (1).

The presence of small amounts of these microbes is physiological in nature. However, if bacterial titres exceed 1,000 CFU/mL per 1 mL of mucus, they become pathogenic (6). The presence of normal flora may protect against pathogens, while changes in commensal bacterial flora seem to be associated with the pathogenesis of CS (12).

Aerobic gram-negative strains, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli, are isolated from patients with CS, mainly from patients with underlying diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (Pseudomonas spp.) or diabetes mellitus, and immunocompromised patients (neutropenia, HIV). They also dominate in patients repeatedly treated with antibiotics or patients after sinus surgeries (1). The role of fungi in paediatric chronic sinusitis is unclear (2). Some literature data confirm that fungi may induce allergic fungal paranasal sinusitis, colonisation of sinuses or invasive fungal sinusitis (1).

As the disease progresses, a change in the bacterial flora is observed: from the one typical of acute sinusitis to the dominance of β-haemolytic streptococci, coagulase-negative staphylococci and anaerobic bacteria (7). The presence of S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and/or M. catarrhalis strains in the nasopharynx of children with URTIs may increase the risk of progression of acute otitis media into chronic sinusitis. Competition between physiological bacterial flora and respiratory pathogens is an important infection factor (13). Brook (1) confirmed microbiologic concordance between the ear and sinus in 69% of paediatric patients. The most frequently recovered isolates included H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, Prevotella spp. and Peptostreptococcus spp. S. pneumoniae strains were isolated from approximately 30% of children with acute sinusitis. H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis were recovered from 20% of children (2).

Chronic sinusitis involves formation of biofilm, which plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis and persistence of infection (1). Biofilms are bacterial aggregates characterised by increased antibiotic resistance. Studies to develop an optimal approach to biofilm elimination are underway (2). Studies using an electron microscope confirmed biofilm formation in 88-99% of paediatric patients. Biofilm formation was observed in only 6% of children after tonsillectomy (3).

Diagnosis and treatment of CS

Chronic paranasal sinusitis has a major impact on the health and quality of life in the paediatric population. The treatment of CS in children poses a major challenge due to poorly defined pathophysiology, epidemiology and diagnostic criteria (4). The aim of CS therapy is to improve sinus drainage, reduce chronic inflammation and eliminate pathogens. Children with odontogenic infections should be provided with appropriate dental care and treatment. Effective treatment in patients with CS often requires the combined use of local or oral glucocorticoid therapy, antimicrobials, and moisturizing of the nasal mucosa. If these agents are ineffective, surgical treatment should be considered (1).

Patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms may remain under surveillance for 7-10 days without the use of pharmacotherapy. This will allow for avoiding unnecessary antibiotic therapy in patients with viral infections, which resolve after several days. If no improvement is observed, antibiotic therapy should be considered. Although acute bacterial sinusitis may resolve spontaneously in 50 to 60% of cases without the use of antibiotic therapy, it is usually treated with antibiotics (1). Antibiotic therapy is usually used for 10 to 14 days (2). The use of an antibiotic is also indicated for acute CS exacerbations (1). Reduced blood supply in chronic sinusitis may prevent optimal antibiotic levels at the site of infection even when therapeutic serum antibiotic levels are reached. Furthermore, specific conditions in sinuses with reduced pH and oxygen tension affect antimicrobial efficacy (1). At least 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy are recommended in chronic sinusitis (2).

The efficacy of antibiotic therapy arouses considerable controversy, mainly due to the spreading antibiotic resistance, and the nature of the disease, which is often unrelated to microbial invasion. Antibiotics are often used as perioperative prophylaxis (14). Oral administration is the most frequently used route of administration in antibiotic therapy. Parenteral administration is used in children with severe conditions, undergoing surgical treatment or patients having problems with oral medication (1).

The choice of appropriate antibiotic therapy for patients with sinusitis is a major problem. Excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics contributes to the widespread multidrug resistance of bacteria.

Empirical antibiotic therapy is usually used at the initial stage of CS treatment. Patients who failed to respond to previous treatment are an exception (1). The selected antibiotic therapy should target the most probable bacterial pathogens, both aerobic (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis) and anaerobic (Fusobacterium spp., Prevotella spp., Porphyromonas spp. and Peptostreptococcus spp.). Coverage for MRSA may also be indicated (1). The antimicrobials used often fail to cover gram-negative bacteria, contributing to therapeutic failure and/or chronicity of the disease process (15).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends amoxicillin as first-line antibiotic therapy in non-complicated, mild-to-moderate sinusitis in children under 2 years of age. Second-generation cephalosporins (cefprozil, cefuroxime or cefpodoxime) are an alternative for penicillin-allergic patients. Patients presenting with severe symptoms or those after recent unsuccessful antibiotic therapy should be treated with high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid regimen is also a second-line therapy for patients with clinical failure after 48-72 hours of treatment with amoxicillin. Intramuscular or intravenous ceftriaxone may be used in patients with intolerance to oral therapy. Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, erythromycin, sulfisoxazole and first-generation cephalosporins (cefalexin, cefadroxil), which were often used in the past, are no longer indicated for the treatment of sinusitis due to high resistance rates for H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae and M. catarrhalis (2).

Bacterial virulence factors, which are mainly located in the mobile genetic elements allowing for their easy transmission between organisms via horizontal gene transfer, are increasingly considered in the therapy. The ability of bacteria to form biofilms also contributes to therapeutic failures in children with CS. A biofilm prevents the penetration of antibiotic and contributes to bacterial resistance to antibiotics (15). Rinsing the sinuses with saline helps disrupt the biofilm structure. Studies on tonsil sections obtained from the affected children demonstrated that the biofilms contained in these sections could be a reservoir for chronic and recurrent infection. Adenoidectomy contributed to the release of symptoms in many patients with CS (4).

Surgical treatment should be considered the last resort in the paediatric population. Surgical intervention may be considered in acute sinusitis if there is a risk of intracranial or orbital complications. A surgery to unblock obstructions and eliminate infection foci is also considered in chronic refractory sinusitis and in cases of previous antimicrobial treatment failures (2).

Surgical treatment includes adenoidectomy, balloon sinuplasty, and functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS). Nasal irrigations and drops to reduce mucosal oedema are additionally used. Antihistamine agents and leukotriene receptor antagonists are indicated in children with allergic rhinitis (3).

The goal of FESS is to open more widely and clean the maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses. It also allows for restoring proper sinus ventilation (2). FESS is usually performed in patients with acute and chronic sinusitis who fail to respond to conventional treatment (16). The procedure is also indicated in children with cystic fibrosis, nasal polyps or fungal allergic sinusitis (3).

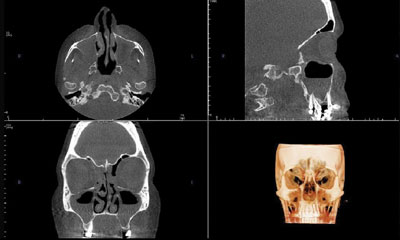

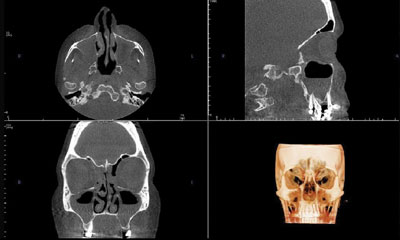

Diagnostic imaging is often problematic in the paediatric population. Computed tomography (CT) of paranasal sinuses often requires general anaesthesia in children (fig. 1, 2). Therefore, CT scan is reserved for preoperative planning of FESS (4).

Fig. 1. Computed tomography

Fig. 2. Computed tomography

Sinus radiograms are not necessary to confirm sinusitis in symptomatic children aged 6 years or less. Literature data show an 88% correlation between acute sinusitis and radiographic findings in this age group. The correlation is lower (70%) in children older than 6 years; therefore radiography may be considered in this group. Many physicians order sinus radiography to exclude sinusitis in patients with ambiguous symptoms (2).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not used in paediatric sinusitis imaging due to high costs and the need for general anaesthesia. MRI is indicated if it is necessary to visualise the site of discharge retention, thickened mucosa or to differentiate between inflammatory and neoplastic lesions and diagnose allergic fungal sinusitis (2).

In the case of CS, many doctors suggest FESS without previous antibiotic therapy (1). Tan et al. (2) showed that FESS ensured higher therapeutic success vs non-invasive methods alone in a 10-year period in a study investigating patient satisfaction. Although FESS shows efficacy in paediatric patients, it still raises concerns associated with its possible effects on the development of the facial skeleton (4).

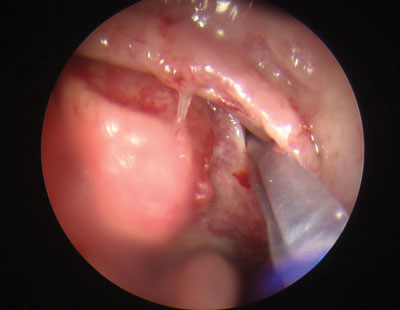

FESS may be combined with endoscopic sinus irrigation (Hydrodebrider), which helps remove inflammatory secretions and bacterial biofilms from the paranasal sinuses. Sinus irrigation allows for simultaneous administration of medications and antibiotics into the sinuses (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Sinus irrigation

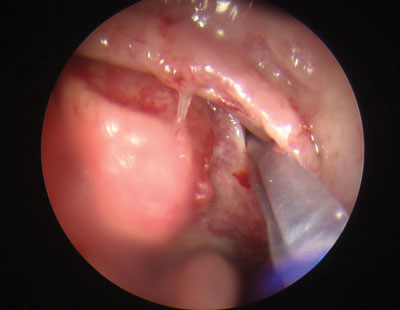

Balloon sinuplasty, which is a relatively new technique, may be used in children > 5 years of age (fig. 4). Balloon sinuplasty involves an introduction of a small balloon catheter through the nasal cavity into the sinus ostia. The balloon is filled with fluid under pressure from a few to several atmospheres, allowing for effective and permanent unblocking of sinus ostia and removal of discharge (17). Balloon sinuplasty helps unblock sinuses and restore normal drainage. It allows treating bacterial and fungal infections. Convalescence after the procedure is short; the patient may be discharged home already after several hours. Indications for balloon sinuplasty include sinusitis with polyps, injuries and previous sinus surgeries. Since the technique is minimally invasive, it is considered safe and applicable in children (17).

Fig. 4. Balloon sinuplasty

In addition to antibiotic and surgical treatment, adjuvant therapy is also used in children with sinusitis. Physiological saline moisturizers, steam inhalation, mucolytic agents to dilute secretions, and vasoconstrictors are helpful in reducing nasal mucosa oedema and removing thick residual discharge (2). Nasal steroids are useful as an adjuvant treatment. Steroids reduce nasal mucosal oedema in children with allergic rhinitis. The use of nasal steroids has only limited benefits in patients with sinusitis and is indicated mainly in patients with polyps and significant nasal congestion (2).

Sinus bacterial flora in children – own experience

A total of 112 swabs were taken and 121 isolates were recovered from 71 paediatric CS patients treated in the MML Medical Centre between 2015 and 2017. Details on the number of recovered strains are shown in table 1.

Tab. 1. The number of strains recovered from patients with CS depending on the sampling site

| Sampling site | Number of isolates |

| Maxillary sinuses | 71 |

| Nasal cavity | 14 |

| Auditory canal | 17 |

| Pharynx | 12 |

| Tonsils | 3 |

| Nasopharynx | 3 |

| Oral cavity | 1 |

Staphylococci were the most frequently recovered strains. A total of 36 S. aureus strains and 31 S. epidermidis strains were isolated. Typical respiratory pathogens accounted for only a small percentage of all recovered microbes. Statistical data imply that upper respiratory tract pathogens do not play an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic sinusitis. No bacteria were isolated from 18 swabs. The prevalence of different bacteria is shown in table 2.

Tab. 2. The prevalence of different bacterial species in the material obtained

| Bacterial genus/species | Number of isolated strains |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 36 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 31 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 10 |

| Candida spp. | 8 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 6 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 5 |

| Streptococcus mitis | 4 |

| Corynebacterium pseudodiptheriticum | 4 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 4 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 3 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 3 |

| Acinetobacter baumanie | 1 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 1 |

| Prevotella melaninogenica | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 |

| Staphylococus lugdunensis | 1 |

| Trichosporon spp. | 1 |

A total of 61 swabs were taken from the maxillary sinuses in children. A total of 71 strains were grown; no bacterial growth was observed for 5 swabs. The most prevalent maxillary strains are shown in table 3.

Tab. 3. The prevalence of different strains isolated form maxillary sinuses

| Bacterial genus/species | Number of isolated strains |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 31 |

| Staphylococcus ureus | 18 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 4 |

| Corynebacterium pseudodiptheriticum | 4 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 4 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 3 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 2 |

| Streptococcus mitis | 1 |

| Candida spp. | 1 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 |

| Staphylococus lugdunensis | 1 |

Conclusions

Sinusitis, recurrent and chronic in particular, is a major challenge for doctors involved in diagnosing and treating this condition.

An interdisciplinary approach to the problem, including laryngological, microbiological, allergological, biochemical, histopathological consultations and diagnostic imaging, is needed. Resistance of isolated microbes in a given geographical zone or a given population should be considered when choosing antibiotic therapy. Isolation of materials of high diagnostic value (aspirates, tissues) is very important. Determination of virulence characteristics, which ensures full characteristics of strains and appropriate choice of antibiotic therapy, may be indicated in some cases.

Adjuvant therapy involves the use of physiological saline, irrigations, inhalations, nasal and systemic steroids, mucolytics and agents to reduce congestion. It is also important to identify and treat factors that predispose to sinusitis, such as viral upper respiratory tract infections, allergic rhinitis, structural nasal anomalies and immune deficiency.

Further research is needed to determine the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of sinusitis, including their ability to form a biofilm. It seems particularly important to compare the number and type of microbes in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses during exacerbations and remissions.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Brook I: The role of antibiotics in pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2017; 2(3): 104-108.

2. Tan R, Spector S: Pediatric sinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2007; 7(6): 421-426.

3. Stenner M, Rudack C: Diseases of the nose and paranasal sinuses in child. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 93 (suppl. 1): S24-48.

4. Criddle MW, Stinson A, Savliwala M, Coticchia J: Pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis: a retrospective review. Am J Otolaryngol 2008; 29(6): 372-378.

5. Halawi AM, Smith SS, Chandra RK: Chronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and cost. Allergy Asthma Proc 2013; 34(4): 328-334.

6. Stevens WW, Lee RJ, Schleimer RP, Cohen NA: Chronic rhinosinusitis pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015; 136(6): 1442-1453.

7. Hamilos DL: Problem-based learning discussion: Medical treatment of pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2016; 30(2): 113-212.

8. Michalik M, Podbielska-Kubera A: Wpływ schorzeń zatok na procedury implantologiczne. Forum Stomatologii Praktycznej 2018; 1-2: 26-30.

9. Manes RP, Batra PS: Etiology, diagnosis and management of chronic rhinosinusitis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2013; 11(1): 25-35.

10. Anderson M, Stokken J, Sanford T et al.: A systematic review of the sinonasal microbiome in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2016; 30(3): 161-166.

11. Whitby CR, Kaplan SL, Mason EO et al.: Staphylococcus aureus sinus infections in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011; 75(1): 118-121.

12. Jain R, Waldvogel-Thurlow S, Darveau R, Douglas R: Differences in the paranasal sinuses between germ-free and pathogen-free mice. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2016; 6: 631-637.

13. Santee CA, Nagalingam NA, Faruqi AA et al.: Nasopharyngeal microbiota composition of children is related to the frequency of upper respiratory infection and acute sinusitis. Microbiome 2016; 4: 34.

14. Hauser LJ, Feazel LM, Ir D et al.: Sinus culture poorly predicts resident microbiota. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2015; 5(1): 3-9.

15. Michalik M, Samet A, Marszałek A et al.: Intra-operative biopsy in chronic sinusitis detects pathogenic Escherichia coli that carry fimG/H, fyuA and agn43 genes coding biofilm formation. Plos One (w druku).

16. Das A, Biswas H, Mukherjee A et al.: Evaluation of preoperative flupirtine in ambulatory functional endoscopic sinus surgery: A prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Anesth Essays Res 2017; 11(4): 902-908.

17. Hughes N, Bewick J. Van Der Most R, O’Connell M: A previously unreported serious adverse event during balloon sinuplasty – case report. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013.