© Borgis - New Medicine 2/2002, s. 83-88

Andrzej Brzecki, Krystyna Kobel-Buys, Guido Buys

Hallucinations, illusions, and other visual distrubances in neurology

The Center of Rehabilitation for Children and Adults, Mikoszów (Strzelin), Poland

Summary

The authors describe the visual pathway and especially the posterior part of the optic visual radiation and visual representation in the cuneus of the occipital cortex. Almost the entire visual tract is supplied by the posterior cerebral artery, except for central vision representation, which is supplied by a branch of the middle cerebral artery. Therefore, damage to the visual pathway of one hemisphere may cause heteronymous hemianopsia or quadrantanopsia and, less frequently, visual hallucinations and illusions.

Hallucinations and illusions may also occur – exempli gratia – in infectious encephalopathies, poisonings, sleep disorders and psychoses. In particular, stimulation of the temporal lobe by toxins or drugs having dopaminergic, serotoninergic or adrenergic actions (frequently true or „false” neurotransmitters) may also cause them.

Examples of paintings done by artist under the influence of some hallucinogens has been presented. Prosopgnosia and prosopagnosia have been discussed. Prosopagnosia may be caused by an injury the right hemisphere. Anosognosia of the left part of the body and the left visual field have to been also discussed.

A case study of a patient with visual hallucinations and illusions of his own enormous extremities in the course of thrombosis of the posterior cerebral artery has been mentioned. Also, in connection with this theme, we discussed anosognosia of the left part of the body and left visual field spatial neglect, cortical blindness etc. and we mentioned border zone infarcts as a new problem of vascular diseases in elderly patients.

Clinical examples of hypnagogic hallucinations occurring in sleep deprivation and in narcolepsy have been presented.

The problem of different kinds of hallucinations and their relation to the ability to draw or paint in patients with schizophrenia have been discussed and illustrated.

INTRODUCTION

The visual tracts start in the retina, and through the optic nerve, optic chiasma, and optic tract lead to the primary visual centres, to the lateral geniculate body. This has a similar structure to that which is found in the visual cortex, which is why, it is surmised, it has a specific significance in visual perception. Finally, the visual tract reaches the pulvinar and the superior colliculus, and the pretectal area.

The visual tract is later prolonged as the optic radiation, from the ventricular triangle, as the posterior part of the optic radiation splits and runs above and below the calcarine fissure (42). A lesion of the optic radiation, located before the connection with the primary visual cortex, causes superior and inferior quadrantic hemianopsia. Damage to the primary visual cortex (caused by hypoxia, trauma, or tumour, Alzheimer´s degeneration and others) is a cause of cortical blindness, with preserved central vision (macular and fixational), and sometimes with Anton´s syndrome – i.e.: a denial of having cortical blindness. Poor unilateral or bilateral vision may be accompanied by hallucinations and illusions.

The primary or striated visual cortex, called V1 in neurophysiological terms, is supplied by the posterior artery of the brain. This excludes the posterior part, which handles central field vision, and is supplied by a branch of the middle artery (36, 45). The primary visual cortex is surrounded by fields V2, V3, and V4, the medial region of the temporal-occipital region, which is probably responsible for perception of colour and shape (55). An injury to this area causes colour agnosia.

Field V5 in the vicinity of the angular gyrus, and, together with part of the optic radiation, is probably supplied by a branch of the middle brain artery. This field has a special significance in movement perception within the visual field, which continues to operate even after an injury to the primary visual cortex (56). This was demonstrated by Riddoch in 1917 (44).

Descending tracts from the visual cortical centres are parallel to the ascending tracts (24), and serve to control visual stimulation, by feedback. Other descending tracts run to the parietal and temporal lobes, and determine the conscious process of vision as a separate cortical visual pathways, one which is specialised for spatial perception (where an object is) and follows a dorsal route from the occipital to the parietal lobes and the other which is specialised for specifying what an object is and follows a route from the occipital to temporal lobes (54).

Therefore, cutting the descending impulses from the visual cortex may cause a composite agnosia of the face (prosopagnosia), colour vision agnosia, alexia, achromatopsy (colour vision agnosia, or seeing black-and-white objects in colours), and simultant agnosia. In the same way as the ascending tracts, injury may lead to hallucinations and illusions.

Illusions are defined as deformations of normal image: these include metamorphoses (elongation or distortion which may cause, for example seeing a head in a grotesque way, or seeing a picture which is placed in an inappropriate field of vision), micropsy, macropsy, teleopsy (seeing objects from a certain distance), poliopsy, allesthesia (seeing objects in another part of the visual field, which means seeing the object in two different places), polynopsia (overlapping of recently-seen objects on a current image, or perseverance) (9, 33).

Simple and composite hallucinations may be defined as seeing unreal shapes, objects, animals, human beings, or fantastic creatures. The phenomena occur in 10% of cases of amblyopia (hemianopsia) caused by a stroke (28).

In cases of infectious or metabolic encephalopathies, drug abuse, psychoses, sleep disorders, hallucinations and illusions probably occur because of lack of light stimulation, sleep deprivation, and/or cerebral cortex stimulation, caused by real or "false” neurotransmitters (40).

Hallucinations and illusions may occur together with other occipital, temporal, and parietal disturbances (olfactory, gustatory, and other hallucinations). In vascular injury to the posterior region of the optic radiation and visual cortex (which is usually caused by thrombosis or embolus), there is occasional hypotension – this results in insufficient cerebral blood perfusion in the regions supplied by the posterior, anterior or middle brain artery (border zone infarcts) (3, 4, 7, 23, 27, 39, 50).

Less frequently, injury to the optic radiation or visual cortex is caused by arterial hypertension, rupture of an aneurysm, various blood diseases, antithrombotic drugs, haemorrhagic inflammation of the brain, bleeding of a tumour, etc. Among other causes are epilepsy, tumours, brain contusion, inflammation, Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, poisoning, Alzheimer´s disease, and other diseases caused by cerebral atrophy, progressive multi-focal leucoencephalopathy, adrenoleukodystrophy in childhood, and various intoxicants, including poisoning with hallucinogens (11, 12, 26).

Hallucinations and illusions may be present in various eye conditions, retinal degeneration (1), and other eye diseases (49). They may appear in darkness, especially in elderly persons with poor eyesight (16).

Hallucinations and visual illusions are sometimes observed in the states of delirium or obnubilation, or in serious emotional disturbances in schizophrenia, in which latter hallucinations may particularly arise as a result of limited contact with the natural surroundings (53).

The symptoms arising in the primary visual cortex are simple hallucination, i.e.: scotoma, photopsy, or photoma (wavy movements, stripes, mists, and shade). Injury to the posterior part of the optic radiation and descending occipital-parietal fibres and/or occipital-temporal fibres may occasionally be the cause of hallucinations and illusions (8).

An injury of the left (dominant) angular gyrus or its adjacent regions is the cause of Gerstmann syndrome (alexia with agraphia, acalculia, the fingers agnosia, impairment of left-right side orientation), which may be bound up with quadrantic hemianopsia and visual hallucinations (10, 20).

Damage to the connections running from the V1-V3 visual cortex (of the dominant hemisphere) to the angular gyrus manifests hemianopsia and pure alexia, which is sometimes accompanied by visual agnosia and in cases of damage to the angular gyrus with alexia and agraphia.

Damage of the right parietal and temporal lobes maybe the cause of prosopagnosia i.e. inability to recognize a well-known face. The visual stimuli coming from all visual fields (V1-V5) reach mainly the right but also the left hemisphere cortex, where the elements of the face are coded and mental features bound up with them (6).

MRI studies confirm observations that the right occipital-temporal region is responsible for the recognition of the face. Inability to recognize a very well-known face may be a developmental or acquired impairment. Recognition of a face is primary in mental development of the child and enables him to differentiate the mother´s face from others.

The manifestation of "a spirit” (supreme mental functions) may be observed in the face as proud, concentration, impudence, shrewdness and many more, which a talented painter (or photographer) may present as a portrait. Face recognition (prosopgnosia) is associated with the original representation of somebody´s face and emotions, the speech pattern and other features. It is likely that the facial pattern is placed in the right hemisphere of the brain, as suggested by MRIf, CT, PET examinations (18). Pictures of a recognized face may be transferred by talented painters. We have chosen two portraits, which in our opinion perfectly document prosopgnosia (pictures 1, 2).

Picture 1: A Girl With Chrysanthemums by Olga Boznańska, 1894, Muz. Nar. Kraków. The picture is fascinating for its depth of atmosphere and for multi-meaning of the suggested contents, showing for example gentleness, anxiety and alienation (15).

Picture 2: The Portrait Of A Man by Albrecht Dürer. The essence of his mind, pride, dignity, and maturity may be seen (32).

Anosognosia may occur in the patients with both hemiplegia and hemianesthesia, and other symptoms indicating the damage of the right hemisphere. It may also occur in the patients who neglect the left side of the body (do not pay attention to the left side of the body and deny it). Anosognosia may indicate the interruption of the connection of the visual cortex to the right hemisphere or the damage of the central vestibular system (21). It is often accompanied by apraxia.

Anosognosia and unilateral neglect of the body are the examples of disruption of attention processes and indicate that the predominant lesion is in the right hemisphere. The anatomical basis of such a functional differentiation is still unclear (51).

Hemianopsia, irrespective of its causes is usually permanent, while hallucinations and illusions are often transitory. Visual hallucinations arising from the right non-dominant hemisphere occur more often than those arising in the left (dominant) hemisphere. Visual hallucinations resulting as a consequence of stroke are localized in the field of anopsia.

Illusions and hallucinations may also be caused by hyper- and hypothermia (5), cachexia, dehydration, poisoning, hypoglycaemia, hypoxia, hypnosis, serious emotional stress and religious exaltation. In children, a tendency to imagine very lively, fantasizing or ostensible "visions” may occur, falsely perceived as real phenomena (22).

Sleep disorders in children having neurological symptoms (cerebral palsy, or nocturnal, temporal, or occipital epilepsy, blindness, or breathing disorders) may coincide with somnambulism and hypnogogic hallucinations (35, 57).

In drug addicts hallucinations and illusions appear easily after taking narcotics: they may be accompanied by unusual emotional states "visions” and states similar to déjŕ vu.

Drugs that cause hallucinations are usually of herbal origin and have been used since antiquity as magic and sacred medicines, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) has a hallucinogenic action and is found in ergot (Claviceps purpurea). LSD causes hallucinations and illusions, time perception disorder, and psychotic disturbances.

Marihuana (an extract from the leaves and flowers of hemp (Cannabis sativa var. indica) has euphoric and hallucinogenic properties. Peyotl, found in a dried Mexican Cactus (Anhalonium levinii), contains various alkaloids, including mescalin which causes colourful hallucinations and time perception disorders, i.e. minutes seem to last for hours.

Harmine, apart from other heterocyclic alkaloids, may be found in liana (Banisteria caapi) and in Peganum harmala. It causes Parkinson-like symptoms, initiates athetotic movements and may cause colourful hallucinations.

Ibogaine – an alkaloid from the roots of Tabernanthe iboga – has euphoric and hallucinogenic properties (43, 47). Morphine (and its derivatives – heroin, codeine, and others) is the major opium alkaloid. Drug addicts use morphine in injections, or they smoke or chew it.

Euphoria after the administration of morphine is often accompanied by hallucinations and illusions. Cocaine, found in the leaves of Erythroxylon coca, causes addiction connected with hallucinations, sometimes with depression and delusions, sexual arousal and other excited states which may give in to criminal behaviour.

Atropine found in the leaves of deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) and in the leaves of stramonium (Datura stramonium) has stimulating properties; it may cause agitation or seizures and in poisoned patients frequently causes illusions and hallucinations.

Ecstasy and other "street drugs” have similar properties. Mescaline, LSD and amphetamines sought after by drug addicts, may be included in this. Levodope, selegiline, bromocriptine and other anti-parkinson drugs, overdosed or used with other medicines (for example with baclofen) may intensify undesirable symptoms, such as confusion, excitement, and hallucinations.

Doxepin, which inhibits adrenaline re-uptake, may infrequently cause orientation disorder and hallucinations. Amitriptyline inhibits the re-uptake of serotonin and may cause hypo-maniacal states and hallucinations. Propranolol blocks adrenergic receptors b1 and b2 and among other undesirable symptoms may cause depression, sleep disorders and hallucinations. Similarly-acting atenolol can also cause hallucinations. Albuterol (salbutamol) stimulating the b2 receptors may cause undesirable central symptoms, such as sleep disorders, excitement, and hallucinations.

Prozac inhibits serotonin and adrenaline re-uptake to neurons and may occasionally cause depressive states and hallucinations. Methysergide (Deseril, antiserotoninieum) may cause sleep disorders and hallucinations (29, 41, 48). All the above-mentioned substances can also cause hallucinations and mental disorders due to the action of true or "false” neurotransmitters.

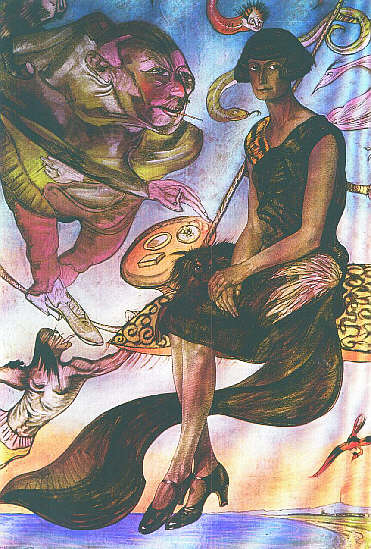

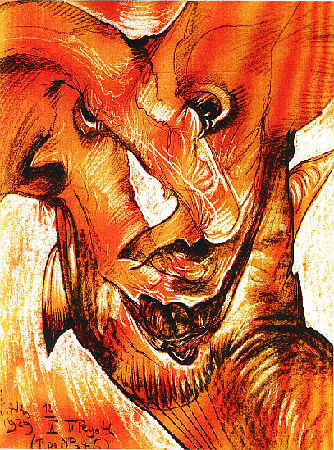

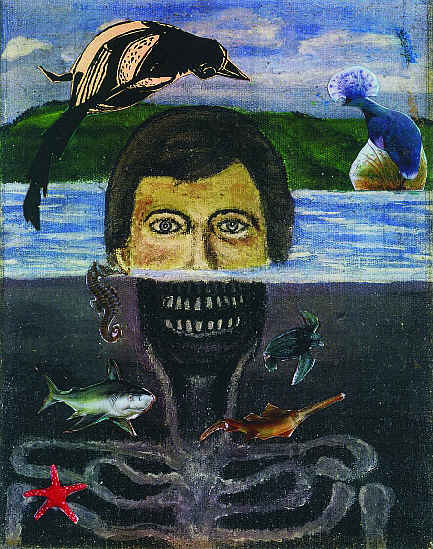

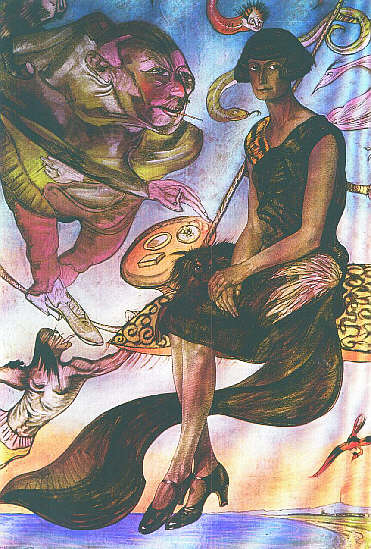

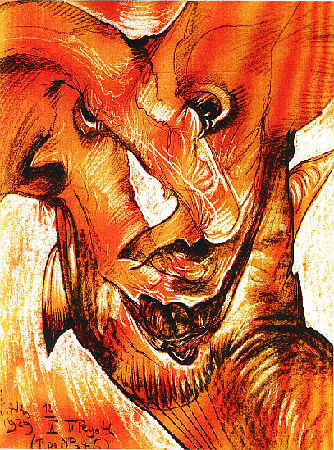

The recording of hallucinations and illusions experienced by a painter, being under the influence of little doses of peyotl or mescaline with alcohol, may be seen in their pictures, for example in the work of the famous Polish artist-printer Witkacy (pictures 3-5). In picture 3 we can see fantastic creatures "being in movement”, as unreal shapes, animals and human beings around the real figure. In picture 4, a maximally-deformed face (illusions). In picture 5 is a grotesquely-deformed mask (rather than face), which is also an example of illusions.

Picture 3: Portrait of M. Nawrocka. The portrait was probably painted after alcohol and mescaline. Around the real figure there are hallucinations of grotesque creatures reminiscent of human beings, serpents and dragons, "being in movement” during the process of transferring them to the picture (25).

Picture 4: Portrait of N. Stachurska, pastel, 1929. A portrait of a real (probably beautiful) face, which is maximally deformed (illusions) painted after alcohol and peyotl (25).

Picture 5: Miss Nena seen after taking mescaline, pencil, drawing (1929). The picture shows a grotesquely deformed snout-like mask (rather than face), with deformed nostrils and spectral eyes, which is an example of an illusory view of a real figure (25).

VISUAL HALLUCINATIONS IN THE COURSE OF THROMBOSIS OF THE POSTERIOR CEREBRAL ARTERY – CASE STUDY

A fifty-two-year-old man with diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, proliferative retinopathy and arterial hypertension, suffered from blurred vision, photopsia, and "flickering”, slightly more intense on the left side. The persistent hemianopsia on the left side occurred. Since then he bas been suffering from simple visual hallucinations. Recently he had dreams about his grotesquely huge left extremities. An MRI study showed an ischaemic region in the cuneus of the right occipital lobe, adjacent to the parietal lobe.

More details of this case have been reported in co-operation with Podemski (14). It represents a new problem about infarcts in the area supplied by the posterior cerebral artery and in border zone territories i.e., the middle and anterior cerebral artery, and it focuses attention on a less common lesion, the "watershed infarct” (38). The arterial hypertension, diabetes, disseminated atheromatosis of cerebral arteries, and the introduction of cardiac surgery and other cardiac treatments for older patients, are causes of syncope episodes, especially in an upright position (orthostatic hypotension) or drop attacks. These episodes often precede bilateral parieto-occipital infarcts with cortical blindness, aphasia, apraxia, hemianopsia and (less commonly) hallucinations. For this reason we have given more clinical details about border zone infarct and its cortical symptoms.

SLEEP DISORDERS AND HALLUCINATIONS

Visual peduncular hallucinosis occurs as a result of midbrain injury, probably in the reticular system (the part of the brain supplied by the posterior cerebral artery), during sleep (31, 34). Hypnagogic hallucinations occur at the onset of sleep and hypnopompic hallucinations at the end of sleep; they are very vivid and colourful, and have also been called psychosensory hallucinations (46). They are one of the symptoms of narcolepsy. The presence of hypnagogic hallucinations has been observed during an excessive flow of blood in the right parietal-occipital region (37). In experiments, these were observed in darkness after the administration of atropine (19). The hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations have to be differentiated from hallucinations which appear in migraine (30). Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations are considered unreal by the patient, contrary to hallucinations resulting from toxic and psychotic states (2). Dreams in REM sleep can be considered as physiological hallucinations and illusions (13).

Hallucinations and illusions (mainly visual) are experienced by people who are isolated in darkness, people living in prolonged isolation (such as solitary sailing or travelling through the desert), on a monotonous car journey and in workers operating automatic machines or performing other functions that do not require constant attention (22, 52).

CLINICAL EXAMPLES OF HYPNAGOGIC HALLUCINATIONS OCCURRING IN SLEEP DEPRIVATION

Five patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (mean age 41 years, mean weight 135 kg) with a high apnoea/hypopnea index (mean: 49 per hour of sleep) and profound arterial oxygen desaturation during sleep (mean: to 78%) had deeply disturbed sleep architecture, with REM sleep consisting of 0-13% (mean: 5% of total sleep time) and with no stage 3+4 of NREM sleep. They suffered from extreme daytime sleepiness and experienced visual hallucinations and illusions:

Case 1: while driving a car, the patient saw a tree in the middle of the road, although he knew that no trees grew there. In another case he saw raindrops on the windscreen of his car and turned on the wipers, although he knew that the sun was shining, strongly.

Case 2: the patient saw a luminous image of an angel, who stretched out his hands to the patient (the patient is strongly connected with a religious sect).

Case 3: the patient saw a cyclist or a car, many times, after awakening.

Case 4: after a tiring day the patient sees enlarging objects (macropsia).

Case 5: a patient had difficulties with making a distinction between his dream and reality, on awakening.

Case 6: a healthy patient without any chronic sleep disorders, when he was 21 years old and on military service duty, after an extremely long march at night had visual hallucinations while he was trying not to fall asleep while walking, and "saw” his barracks. Once again he experienced visual hallucinations after a long sleep deprivation and after many hours of driving a car, when he "saw” other cars and trees on the road, but at the last moment before "collision” he realized that the lane was empty.

CLINICAL EXAMPLE OF HYPNAGOGIC HALLUCINATIONS IN NARCOLEPSY

A forty-four-year-old women, an ex-smoker with chronic bronchitis, had suffered from excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep attacks since she was about 20. She also infrequently experienced episodes of sleep palsy. A sleep study allowed us to exclude sleep apnoea as the cause of her sleepiness. A multiple sleep latency test showed short mean sleep latency (5 minutes). Clinical symptoms and signs confirmed the initial diagnosis of narcolepsy. She was very concerned about her nocturnal hallucinations, which used to occur at the moment of falling asleep. She repeatedly "saw” a colourful person, sitting close to her in a non-existant-armchair and smoking a cigarette. She could still draw her visual hallucinations several days later – picture 6 (all sleep studies were performed in the Polysomnography Laboratory in the Department of Lung Diseases of the University of Medicine in Wrocław).

Picture 6: Hypnagogic hallucinations in patient with narcolepsy. Picture made by the patient.

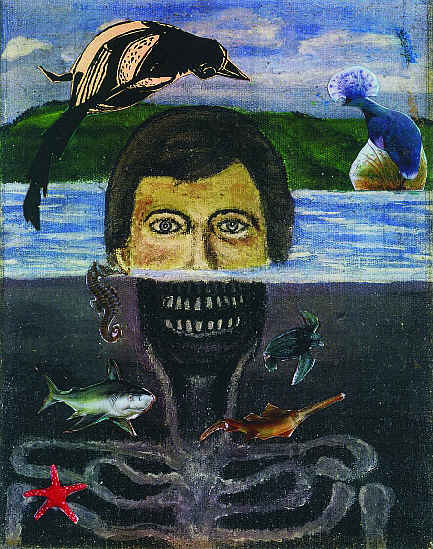

HALLUCINATIONS AND ILLUSIONS IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

In the book "Insania Pingens” written by experts in art and psychiatry (17), the characteristics of patients with schizophrenia, different kinds of hallucinations and some experience in drawing or painting had been presented. One patient with schizophrenia, an educated humanist, was reserved, convinced of her divine mission, indifferent towards other people, very laborious and taciturn, painted her pictures with talent. However, her pictures did not show her visual hallucinations, but were "inspired” by her auditory hallucinations ("I paint, what I hear” – she said).

Another patient with an elementary school education was a schizophrenic and alcoholic. He became a victim of his own persecutory ideas, hostility towards the entire world and he suffered from frequent auditory hallucinations. In the course of time, he was more and more indifferent to others and started to draw, unexpectedly revealing a talent, not previously developed. His pictures did not show the hallucination contents, but contained his memories from the period before he was ill.

Another patient, primitive, with military megalomania, was a commander and was walking with a wooden sword ("everybody must obey orders”); he was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. As time went on he started to draw and paint with talent. His works showed the traces of primitive art and the contents of his hallucinations and visual illusions (unknown faces, deformed silhouettes of animals), or naďve desires, e.g. self-presentation in a military uniform in the company of his imaginary bride.

In these descriptions, according to the authors of the above-mentioned publication, the pictures are imposed by visual, auditory and other hallucinations (very frequent in schizophrenic patients, in the form of "sucking out the brain, electrifying the lungs”). Primitively presented pictures remind us of child´s art, and may have an artistic value, but they are not a sufficient and objective recording of psychological sensations.

In other cases of schizophrenia, there is no essential disintegration of mental activity and other people will not see anything special in the mind of the sick patient. Some painters´ skills may remain at the same, constant level (9). Usually, they surprise us with eccentricity and bizarre presentation. It is difficult to decide whether they are influenced and inspired by hallucinations and illusions or whether this is a mannerism – a difficulty to distinguishing between the world of fantasy and reality. The presented picture (picture 7) entitled "The Encircled”, painted by a patient with schizophrenia, shows, the above-mentioned problem of difficulty distinguishing and separating hallucinations and illusions from eccentricity and whimsy.

Picture 7: The Encircle, 1997. From the private collection of one of the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to: Anna Łuczyńska for a warm-hearted review of our article; Anna Brzecka for making available the case studies of live patients with sleep apnoca, and her kind remarks on hypnagogic anhypnopomic hallucinations; Elżbieta Charazińska and Agnieszka Gorawińska for comments on Olga Boznańska´s picture "A Girl with Chrysanthemums” (Wydawnictwo Arkady); Irena Jakimowicz for valuable interpretations of Witkacy´s pictures in the collection of Wydawnictwo Auriga; Janusz Grasza for translation from the Polish language and John Anderson for correction of the English version.

Piśmiennictwo

1. Abraham H.D.: Visual hallucinations in macular degeneration. Am. J. Psychiatry, 1993, 150, 11:1738. 2. Aldrich M.: Cardinal Manifestations of Sleep Disorders. Chapter 38, Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Edit.: Cryper M., Roth T., Dement D.C., Saunders, Philadelphia, 1989, 422. 3. Anderson R.E. et al.: Effects of glucose and PaO2 modulation on cortical intracellular acidosis, NADH redox state and infarction in the ischaemic penumbra. Stroke, 1999, 30, 1:160-70. 4. Back T.: Pathophysiology of the ischaemic penumbra – revision of the concept. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol., 1998, 8, 6:621-38. 5. Baldwin M., Hofmann A.: Hallucinations. Chapter 17. Disorders of speech, perception and symbolic behavior. Edit.: Vinken P.J., Bruyn G.W., 1980, 327-333. 6. Beale J.M., Keil F.C.: Categorical effects in the perception of faces. Cognition, 1995, 57, 3:217-239. 7. Belden J.R. et al.: Mechanisms and clinical features of posterior border-zone infarcts. Neurology, 1998, 12, 53, 6:1312-8. 8. Benson M.T., Rennie I.G.: Formed hallucination in the hemianoptic field. Postgrad. Med. J., 1989, 65:756-7. 9. Bilikiewicz T.: Psychiatria Kliniczna. PZWL, Warszawa, 1969. 10. Bing R.: Lehrbuch der Nervenkrankheiten. Benno Schwabe & Company, Basel, 1953. 11. Borruat F.X.: Visual hallucinations and illusions, symptoms frequently misdiagnosed by practitioner. Klin. Monatsbl. Augenheilkd., 1999, 214, 5:324-7. 12. Bosley T.M. et al.: Recovery of vision after ischaemic lesions: PET tomography. Ann. Neurol., 1987, 21, 5:444-50. 13. Bradley W.G. et al.: Neurology in Clinical Practice – Vol. I; Major Physiological Changes During Sleep, Approach to a common neurological problem. Butterwortg-Heinemann, Boston-Wellington, 1989. 14. Brzecki A. et al.: Illusions and hallucinations in posterior cerebral artery thrombosis – a case study. Udar mózgu. 2001, 3, 2:71-76. 15. Charazińska E., Morawińska A.: Olga Boznańska. Wydawnictwo Arkady, 1997. 16. Chen J. et al.: Visual hallucinations in a blind elderly woman: Charles Bonnet syndrome, an underrecognised clinical condition. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry, 1996, 18, 6:453-5. 17. Cocteau J. et al.: Insania Pingens. Ciba, Basel, 1961. 18. De Renzi E. et al.: Prosopagnosia can be associated with damage confined to the right hemisphere. An MRIf and PET study and review of literature. Neuropsychology, 1994, 32, 8:893-902. 19. Fisher C.M.: Visual Hallucinations on eye closure associated with atropine toxicity. Can. J. Neurol. Sci., 1991, 18, 1:18-27. 20. Frąckowiak R.S.J. et al.: Human Brain Function: Maps of Somatosensory systems. Academic Press, 1997. 21. Geminiami G., Bottini G.: Mental representation and temporary recovery from unilateral neglect after vestibular stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, 1992, 55:332-3. 22. Gregory R.: Eye and Brain. The Psychology of Seeing. Fifth Ed. Oxford Press, 1998. 23. van der Grond J. et al.: Assessment of border-zone ischaemia with a combined MR imaging-Mr-angiography-MR spectometry protocol. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 1999, 9, 1:1-9. 24. Hanaway J. et al.: The Brain Atlas, Fitzgerald Press Bethesda, Maryland, 1998, 202-3. 25. Jakimowicz I.: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. Auriga, 1985. 26. Kasten E. et al.: Chronic visual hallucinations and illusions following brain lesions. A single case study. Fortschr. Neurol. Psychiatr., 1998, 66, 2:49-58. 27. Kolh P. et al.: Cardiac surgery in octogenarians; peri – operative outcome and long – term results. Eur. Heart J., 2001, 22, 14:1159-61. 28. Kolmel H.W.: Complex visual hallucinations in the hemianoptic field. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr., 1985, 48, 11:20-38. 29. Kostowski W.: Podstawy Farmakologii. PZWL, 1999. 30. Lendvai D. et al.: Migraine with visual aura in developing age: visual disorders. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci., 1999, 3, 2:71-4. 31. Lhermitte J.: Les hallucinations, 1951, Paris, cyt. Brain´s Diseases of the Nervous System, 8 Edit., Rev. by Walton J. M. Oxford Press, New York Toronto, 1977, 1172. 32. Lüdecke H.: Albrecht Dürer – Eine Auswahl aus seinem Werk mit einer Einleitung. Seeman Verlag, Leipzig, 1956. 33. Matthews G.G.: Neurobiologia. PZWL, Warszawa, 2000. 34. McKee A.C. et al: Peduncular hallucinosis associated with isolated infarction of the substantia nigra pars reticulata. Ann. Neurol., 1990, 27:500-4. 35. Menkes J.: Textbook of Child Neurology. Williams & Wilkins, 1998. 36. Merrit´s Neurology, 10 Edition, edit. by Rowland P., Lippincott – Wiliams & Wiliams, Philadelphia-Tokyo, 2000. 37. Meyer J.S. et al.: Sleep apnoea, narcolepsy and dreaming: regional cerebral haemodynamics. Ann. Neurol., 1980, 7, 5:479-85. 38. Mumenthaler M., Mattle H.: Neurologia. Urban & Partner, Wrocław, 2001, 408. 39. Newman R.P. et al.: Altitudinal hemianopsia caused by occipital infarctions. Clinical and computerized tomographic correlations. Arch. Neurol., 1984, 41, 4:41-8. 40. Phelps M.E. et al.: Tomographic mapping of human cerebral metabolism visual stimulation and deprivation. Neurology, 1981, 31, 5:517-29. 41. Podlewski J., Chwalibogowska-Podlewska A.: Leki Współczesnej Terapii. Split Trading, Warszawa, 1994. 42. Rauber-Kopsch F.: Lehrbuch und Atlas der Anatomie des Menschen. Band III, Nervensystem u. sienes Organe, G. Thieme, Leipzig, 1953. 43. Raymond-Hamet M.: Sur uncas remarquable d´antagonisme pharmacologique (Mediate and intermediate effects of ibogaine on the intensine), Comp. Rend. Soc. Biol., 1941, 135:176-179. 44. Riddoch G.: Dissociations of visual perception due to occipital injuries, with especial reference to appreciation of movement. Brain, 1917, 40:15-57. 45. Salamon G., Lazorthes D.G.: Atlas of the arteries of the human brain. Sandoz Editions, Paris, 1971. 46. Schiller F.: The inveterate paradox of dreaming. Arch. Neurol., 1985, 42, 9:903-6. 47. Schultes R.E., Hoffman A.: Tabernanthe Iboga. In: Schultes R.E.; Hoffman A. eds. The botany and chemistry of hallucinogenes. Sprinfield: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 1980, 235-9. 48. Seńczuk W.: Toksykologia. Podręcznik dla studentów farmacji, PZWL, Warszawa, 1990. 49. Sichart U., Fuchs T.: Visual Hallucinationes in elderly patients with reduced vision: Charles Bonnet syndrome. Klin. Monatsbl. Augenheilk., 1992, 3:224-7. 50. Szpak G.M. et al.: Border zone neovascularisation in cerebral ischaemic infarct. Folia Neuropatholol., 1999, 37, 4:264-8. 51. Viader F.: Perception in space. Visual aspects of space perception. Rev. Neurol. (Paris), 1995, 151:8-9, 466-73. 52. Voskresenskii V.A.: Clinical signs of hypnotically suggested visual hallucinations (review). Zh. Nevropat. Psihiatr. S.S. Korsakoff., 1983, 83, 6:925-8. 53. Walton J.N.: Brain´s Diseases of the Nervous System. Revis. Oxford, Univ. Press, New York Toronto, 1977, 790. 54. Wilson B.A. et al.: Knowing where and knowing what: a double dissociation, Cortex 1997, 33, 3:529-41. 55. Zeki S.: A century of cerebral achromatopsia. Brain, 1990, 118:1721-77. 56. Zeki S.: Dynamism of a PET Image; studies of visual function. Chapter 9 w: Frackowiak R.S.J., Fried K.J., Dolan R.J., Matzziota J.C.: Human Brain Function, Academic Press, 1997, 163-82. 57. Zucconi M., Bruni O.: Sleep disorders on children with neurologic diseases. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol., 2001, 8.