© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 3/2014, s. 154-161

*Ewa Winnicka1, Dorota Majak2, Anna Rybak1

Charakterystyka kliniczna i wyniki wideofluoroskopowej oceny aktu połykania u dzieci z zaburzeniami połykania

Clinical characteristics and videofluoroscopic swallowing study findings in children with swallowing disorders

1Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Disorders, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warszawa

Head of Department: prof. Józef Ryżko, MD, PhD

2Department of Imaging Diagnostics, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warszawa

Head of Department: Elżbieta Jurkiewicz, MD, PhD

Streszczenie

Wstęp. Zaburzenia połykania są istotnym, ale często niedocenianym i nierozpoznanym problemem u dzieci. Czasem prowadzą do zachłystowego zapalenia płuc.

Cel pracy. Celem pracy jest przedstawienie metod terapeutycznych i efektów wideofluoroskopowej oceny aktu połykania (VFSS) u dzieci z różnymi chorobami i objawami zaburzeń połykania leczonych w Klinice Gastroenterologii, Hepatologii i Zaburzeń Odżywiania w Polsce.

Materiał i metody. Do badania retrospektywnego zakwalifikowano 36 dzieci. Wszyscy pacjenci prezentowali zaburzenia połykania, w związku z czym zostali skierowani na badanie VFSS. Wskazania do VFSS zostały określone przez lekarza i logopedę. Wyniki zostały zweryfikowane przez radiologa i logopedę. Sposoby karmienia, kompensacji lub rehabilitacji zostały zalecone przez logopedę. Przeanalizowano problemy z połykaniem, wyniki VFSS oraz zalecenia po badaniu.

Wyniki. Powodem wykonania VFSS było określenie „bezpieczeństwa połykania” (17 dzieci) lub ocena funkcjonalności połykania (15 dzieci). U pozostałych pacjentów powodem VFSS była jednoczesna ocena bezpieczeństwa i funkcjonalności połykania (4 dzieci). U 22 dzieci (61%) wystąpiły objawy z układu oddechowego wskazujące na konieczność wykonania VFSS. Ciche aspiracje zostały zauważone u 15 pacjentów, aspiracje z kaszlem u 2, zalegania w gardle u 6, zalegania wraz z penetracją u 6 spośród wszystkich pacjentów. Wyniki VFSS wskazały na konieczność zmodyfikowania karmienia doustnego u 19 dzieci (53%). U 12 pacjentów (33%) odstawiono karmienie doustne. Rehabilitacja bez karmienia doustnego została zalecona u 13 pacjentów (36%), ogólna rehabilitacja połykania ze stosowaniem karmienia doustnego u 11 dzieci (30%). Kompensacja z wykorzystaniem różnych konsystencji pokarmu zastała wykorzystana u 9 pacjentów (25%), kompensacja przez pozycjonowanie i zmodyfikowanie techniki karmienia została podjęta u 16 dzieci (44%). Terapię zaburzeń karmienia zalecono u 8 dzieci (22%).

Wnioski. Metoda jest przydatna w zakresie identyfikowania i diagnozowania problemu z połykaniem. VFSS pozwala na dokonanie wyboru właściwego leczenia i określenie sposobu karmienia odpowiedniego względem różnych patofizjologicznych mechanizmów zaburzeń połykania u dzieci.

Summary

Introduction. Swallowing disorders are a relevant but often unrecognized and underestimated problem in children. Sometimes they lead to aspiration pneumonia.

Aim. The aim of this study was to show the usefulness of the videofluoroscopic swallowing studies’ (VFSS) findings in children with various diseases and symptoms of swallowing disorders based on experiences of the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Disorders in Poland.

Material and methods. A total of 36 children were enrolled in this retrospective study. All patients presented swallowing disorders, therefore they were referred to VFSS. Indications for VFSS were defined by a physician and speech-language pathologist. The outcomes were reviewed by a radiologist and speech-language pathologist. Type of feeding, compensation or rehabilitation was recommended by speech-language pathologist. The swallowing problems, VFSS findings and recommendation after examination were analyzed.

Results. The reason for VFSS referral was “the safety of swallowing” (17 children) or the assessment the function of swallowing (15 children). For the rest of patients the reason for VFSS was the simultaneous evaluation of the safety and function of swallowing (4 children). 22 children (61%) presented with respiratory symptoms as a cause of swallowing disorders and the necessity for VFSS. Silent aspiration was observed in 15 of patients, aspiration with cough in 2, pharyngeal residue in 6, residue with penetration in 6 of all patients. The VFSS outcomes indicated the necessity to modify oral feeding in 19 children (53%). In 12 patients (33%) oral feeding was discontinued. Rehabilitation without oral feeding was ordered in 13 patient (36%), general swallowing rehabilitation with the oral use of foods in 11 children (30%). Compensation using different food consistency was used in 9 patient (25%), compensation by proper positioning and modified feeding technique was adopted in 16 children (44%). Feeding disorders therapy was ordered in 8 children (22%).

Conclusions. This method is helpful for defining and diagnosis the problem with swallowing. VFSS allows to choose a proper therapy and to determine the way of feeding accordingly to different pathophysiologic mechanisms of swallowing disorders in children.

Introduction

Swallowing is a phased process. It is composed of 3 to 5 phases, depending on the definition of the oral phase and its division into 2 or 3 stages, which are as following: a food intake process, bolus forming stage and initiation of pharyngeal phase (1, 2). According to the location of each phase, it is easier to distinguish 3 stages: the oral phase, the pharyngeal phase and esophageal phase. The oral phase is volitional, while the pharyngeal and esophageal ones are achieved according to the reflex actions. The crucial part of the oral phase is the food intake, its processing through crumbling it and melting it with saliva (depending on food consistency we can distinguish biting off, biting, crushing and chewing) and moving the bolus to the back of the oral cavity in order to initiate the pharyngeal phase. The oro-motor phase is carried directly due to the effective functioning of lips, tongue, jaw and cheeks, and indirectly through the face and neck muscles. The pharyngeal phase begins with the activation of the reflex actions, which protects the closing of the respiratory tract during this phase, and moving the bolus towards the pharyngo-esophageal sphincter (UES). In order to do so, the soft palate gets tensed, and together with the adjoining throat’s walls form a palato-pharyngeal closure, which prevents the bolus from getting to the nasal cavity. Another reflex action simultaneously protects the entrance to the respiratory tract through the lifting of the larynx and pushing it forward, together with the closure of the epiglottis and the vocal cords. Larynx displacement is possible due to the prior move of the hyoid bone, this pulls the larynx and it is a trigger for UES opening. The passage of food through the UES to the esophagus is the beginning of the esophageal phase. This phase consists of the bolus passage to the stomach due to the esophageal peristalsis. Bolus passing through the gastro-esophageal sphincter is thought to be the last stage of the swallowing process. The motor control during the pharyngeal phase is conducted by the bottom muscles of the oral cavity, pharyngeal muscles, and muscles of the neck and larynx. The esophageal phase is controlled by UES muscles, esophageal muscles and LES muscles.

The neurological control of swallowing process involves different parts of nervous system – from the brain stem which is responsible for inborn swallowing reflexes, to the central uppermost level of the central nervous system, such as motor and pre-motor cortex, which takes over the control over food intake and swallowing upon child’s maturation. Simultaneously, the motor habits are imprinted as well as the will-dependent motor skills (3).

The function of swallowing may be compared to the effective system of generated pressures and penstocks, which control the transit of food bolus from the front of the oral cavity to the stomach. The tightness and tension of mouth, esophago-pharyngeal closure, and gastro--esophageal sphincter are the components of the penstocks system helping in controlling the food transit. The functioning of the tongue, cheeks, clenching of pharyngeal muscles and peristalsis of esophagus create a system of generated pressures, which contributes to food transfer (sometimes against the gravity).

The swallowing disorders (dysphagia) may appear at any stage of the process and they may apply to either one or more phases of the swallowing process. The problems may include bolus formation, oral transit, initiation of the pharyngeal phase, transit to the esophagus, opening of the upper esophageal sphincter, transit through the lower esophageal sphincter. Particular concern relates to the timing and coordination deficits that may result in aspiration (4).

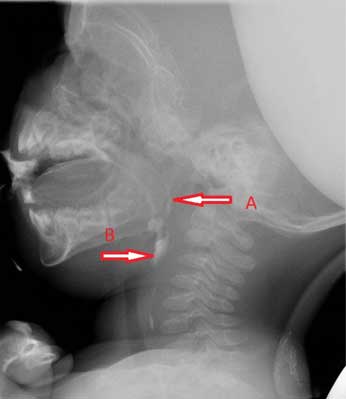

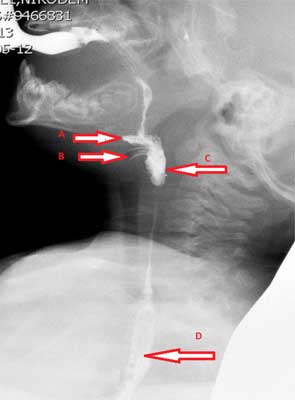

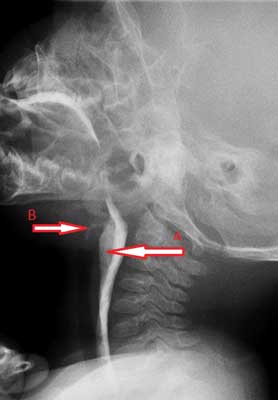

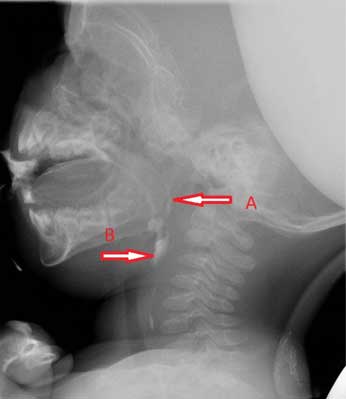

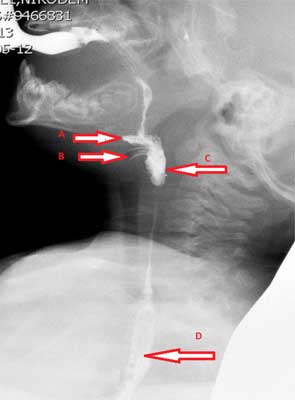

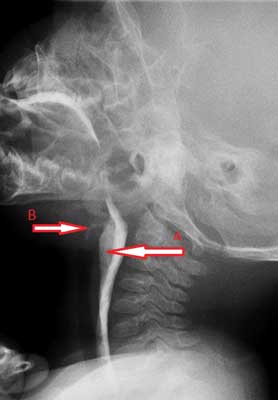

Oral phase disorders may lead to some problems with keeping food within the oral cavity and cleaning it off food. They also can cause inability to effective bite crumbling and its transition from the front part of the oral cavity to the back part, which often results in low feeding efficiency. During the pharyngeal phase, disorders may manifest through the food aspiration into the low respiratory tract (fig. 1), its penetration into the nasal cavity (fig. 2), and residue in the pharynx (fig. 3 and 4). When assessing the esophageal phase, the attention is usually paid to detect potential esophageal narrowings, tracheo-esophagal fistulas and reverse passage of food through UES to pharynx.

Fig. 1. Penetration (A) Passing in Aspiration (B).

Fig. 2. Penetration in Nasopharynx (A) and Residue in Pyriform Sinuses (B).

Fig. 3. Material in Valleculae (A), Penetration (B), Residue in Piryform Sinuses (C), Bolus in Esophagus (D).

Fig. 4. Residue in Pyriform Sinuses (A) with Penetration (B).

Videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing process can be used to evaluate each of the phases. During the oral phase, we check the functioning of the particular elements in oral cavity, transfer of the bolus to the back parts of oral cavity and effectiveness of oral cleaning. During the pharyngeal phase, we can evaluate the rapidity of the reflex action’s activation due to the food transit to the pharynx, coordination of successive activation of the reflex actions, the efficiency of closing and opening the particular elements of the pharynx, the effectiveness of respiratory tract protection against food aspiration and pharyngeal cleansing at the end of this phase. The evaluation of esophageal phase consists of evaluating the food passage through the esophagus (5).

The test consists of giving a contrast medium melted food to a patient, what enables assess swallowing act while using observation and recording on videotape the images appearing on a fluoroscopic screen. Since, a child has to take the food orally and swallow it voluntarily, a cooperation with patient is required in order to perform this examination. A speech therapist and radiologist are engaged to the examination. However, a presence and help of parents is often necessary. A food used in the VFSS should resemble the one which parents feed their child with. Apart from food intake and swallowing act, feeding technique is evaluated.

Aim

The aim of this study was to show the usefulness of the videofluoroscopic swallowing studies’ (VFSS) findings in children with various diseases and symptoms of swallowing disorders based on experiences of the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Disorders in Poland.

Material and methods

Subjects

We enrolled 36 children with swallowing disorders treated in Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Disorders to the study, who underwent VFSS between April 2012 and October 2013. If a patient underwent VFSS more than once during the study period, only the first VFSS findings was analyzed.

Methods

Clinical characteristic including medical conditions associated with swallowing disorders, and the occurrence of symptoms from respiratory system were evaluated. All patients presented with swallowing disorders and despite of this, suffered from neurological, cardio-respiratory, anatomic-functional or gastrological problems. Indications for VFSS were defined by a physician and speech-language pathologist. Outcomes were reviewed by a radiologist and speech-language pathologist. A type of feeding was defined before and after VFSS. A type of compensation or rehabilitation was recommended by speech-language pathologist.

The problems of patients with dysphagia were divided into 4 groups: neurologic disorders, cardio-respiratory problems, anatomical and functioning disorders, and gastrological problems. The group of neurologic patients was not homogenous with regard to the symptoms intensity. It comprised of infantile cerebral palsy, drug-refractory epilepsy, ischemic and anoxic encephalopathy, psycho-motor retardation, and problems with appropriate muscle strength and tension. Among the patients with gastrological disorders, there were undernourished children, patients presenting with excessive vomiting, feeding disorders, and gastro-esophageal reflux disease. The cardio-respiratory disorders comprised heart defects, broncho-alveolar dysplasia, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, and respiratory failure. Esophagus atrophy, burn of oral cavity and esophagus, larynx atresia, cleft palate or cleft lip belonged to anatomical and functioning disorders. Nine patients (25%) were included into more than one group because of concomitant diseases.

Another classification was based on patient’s previous respiratory symptoms indicating potential risk of food aspiration or swallowing-breathing coordination disorders. Respiratory disorders, which might lead to swallowing problems, included pneumonia, bronchitis, recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, wheezing and whistling either during feeding or just after feeding process (6, 7). In this cases, the aim of the study was to determine the safety of swallowing (8). The indication for VFSS to evaluate swallowing process in these patients was an insufficient food intake in relation to daily requirements, frequently accompanied by malnutrition, as well as anatomical and functioning disorders influencing safety and efficiency of swallowing.

VFSSs were conducted as described by Arvedson with some modifications. The day before examination, speech language pathologist was observing child’s natural feeding process; either while eating by him/herself or being fed by its parents/caregivers. Afterwards, a speech language pathologist was feeding a child by herself in order to determine the level of its hypersensitivity to food stimulus, as well as to observe child’s reaction to a new situation connected with stranger who feed him. Moreover, the type of food, its consistency and feeding techniques were determined to work out an examination plan. Before VFSS the parent formal consent was obtained. During the examination, a child was sitting on its parent’s laps and was fed by a speech language pathologist, however, in several cases, parents fed their child themselves.

Powyżej zamieściliśmy fragment artykułu, do którego możesz uzyskać pełny dostęp.

Mam kod dostępu

- Aby uzyskać płatny dostęp do pełnej treści powyższego artykułu albo wszystkich artykułów (w zależności od wybranej opcji), należy wprowadzić kod.

- Wprowadzając kod, akceptują Państwo treść Regulaminu oraz potwierdzają zapoznanie się z nim.

- Aby kupić kod proszę skorzystać z jednej z poniższych opcji.

Opcja #1

24 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego artykułu

- dostęp na 7 dni

uzyskany kod musi być wprowadzony na stronie artykułu, do którego został wykupiony

Opcja #2

59 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 30 dni

- najpopularniejsza opcja

Opcja #3

119 zł

Wybieram

- dostęp do tego i pozostałych ponad 7000 artykułów

- dostęp na 90 dni

- oszczędzasz 28 zł

Piśmiennictwo

1. Brodsky L, Arvedson JC: Physiology of swallowing. [In:] Arvedson JC, Brodsky L (eds.): Pediatric swallowing and feeding: assessment and management. 2nd ed., Albany: Singular Publishing Group, Division of Thompson Learning, Inc. 2002: 38-48.

2. Logemann J: Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 2nd ed., Austin, TX: Pro-Ed 1998.

3. Brodsky L, Arvedson JC: Neural control of swallowing. [In:] Arvedson JC, Brodsky L (eds.): Pediatric swallowing and feeding: assessment and management. 2nd ed., Albany: Singular Publishing Group, Division of Thompson Learning, Inc. 2002: 49-56.

4. Arvedson JC: Assessment of Pediatric Dysphagia and Feeding Disorders: Clinical and Instrumental Approaches. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2008; 14: 118-127.

5. Arvedson JC: Interpretation of Videofluoroscopic Swallo Studies of Infant and Children. A study guide to improve diagnostic skills and treatment planning. Northern Speech Services, Inc. 2006: 25-30.

6. Vaito A, Bailey GL, Molfenter SM et al.: Swallowing rehabilitation with the oral use of foods voice-quality abnormalities as a sign of dysphagia: validation against acoustic and videofluoroscopic data. Dysphagia 2011; 26(2): 125-134.

7. Tohara H, Saitoh E, Mays KA et al.: Three Tests for predicting Aspiration without Videofluorography. Dysphagia 2003; 18: 126-134.

8. Weir K, McMahon S, Barry L et al.: Clinical signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal aspiration and dysphagia in children. Eur Respira J 2009; 33: 604-611.

9. Barbiera F, Condello S, De Palo A et al.: Role of videofluorography swallowing study in management of dysphagia in neurologically compromised patients. Radiol Med 2006; 111(6): 818-827.

10. Palmer JB, Kuhlemeier KV, Tippett DC et al.: A protocol for the videofluorographyc swallowing study. Dysphagia 1993; 8(3): 209-214.

11. Stuart S, Motz JM: Viscosity in Infant Dysphagia Menagenent: Comparison of Viscosity of Thickened Liquids Used in Assessment and Thickened Liquids Used in Treatment. Dysphagia 2009; 24: 412-422.

12. McCallum S: Addresing Nutrient Density in the Context of the Use of Thickened Liquids in Dysphagia Treatment. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition 2011 Dec; 3(6): 351-360.

13. Choi KH, Ryu JS, Kim MY et al.: Kinematic Analysis of Dysphagia: Sagnificant Parameters of Aspiration Related to Bolus Viscosity. Dysphagia 2011; 26: 392-398.

14. Lee SI, Yoo JY, Kim M et al.: Changes of timing variables in swallowing of boluses with different viscosities in patients with dysphagia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 94(1): 120-126.

15. McCullough GH, Kamarunas E, Mann GC et al.: Effect of Mendelsohn maneuver on measures of swallowing duration post stroce. Top Stroce Rehabil 2012; 19(3): 234-243.

16. Wada S, Tohara H, Lida T et al.: Jaw-opening exercise for sufficient opening of upper esophageal sphincter. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93(11): 1995-1999.

17. Kim BR, Sung IY, Choi KH et al.: Long-term outcomes in children with swallowing dysfunction. Dev Neurorehabil 2013 Jul: 19.

18. To R, Goh W, Wong V: Video-fluoroscopic study of swallowing in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics International 2004; 46(1): 26-30.

19. Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB et al.: Penetration-Aspiration Scale. Dysphagia 1996; 11: 93-98.

20. Pearson Jr WG, Molfenter SM, Smith ZM: Image-based Measurement of Post-Swallow Residue: The Normalised Residue Ratio Scale. Dysphagia 2013; 28: 167-177.

21. Molfenter SM, Steele CM: The Relationship Between Residue and Aspiration on the Subsequent Swallow: An Application of the Normalized Residue Ratio Scale. Dysphagia 2013 Dec; 28(4): 494-500.

22. Allen JE, White CJ, Leonard et al.: Prevalence of penetration and aspiration on videofluoroscopy in normal individuals without dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 142(2): 208-213.

23. Weir KA, McMahon S, Taylor S et al.: Oropharyngeal aspiration and silent aspiration in children. Chest 2011; 140(3): 589-597.

24. Sarraf Shirazi S, Buchel C, Daun R at al.: Detection of swallows with silent aspiration using swallowing and breath sound analysis. Medical &Biological Engineering & Computing 2012; 50(12): 1261-1268.

25. Wang TG, Chang YC, Chen SY et al.: Pulse oxymetry does not reliability detect aspiration on videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86(4): 730-734.

26. da Silva AP, Lubianca Neto JF, Santoro PP: Comparison between videofluoroscopy and endoscopic evaluation of swallowing for the diagnosis of dysphagia in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 143(2): 204-209.

27. Kaye GM, Zorowitz RD, Baredes S: Role of flexible laryngoscopy in evaluating aspiration. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997; 106(8): 705-709.

28. Erasmus CE, van Hulst K, Rotteveel JJ et al.: Clinical Practice Swallowing Problems in Celebral Palsy. Eur J Pediatr 2012; 171: 409-414.

29. Jang YY, Lee SJ, Jeon JY et al.: Analysis of video fluoroscopic swallowing study in patient with vocal cord paralysis. Dysphagia 2012; 27(2): 185-190.

30. van den Engel-Hoek L, Erasmus CE, van Hulst KCM et al.: Swallowing and Identification of dysphagia in children. Kongress ‘Im Gesprach 2013’, The Netherlands.

31. Sheikh S, Allen E, Shell R et al.: Chronic Aspiration Without Gastroesophageal Reflux as a Couse of Chronic Respiratory Symptoms in Neurologically Normal Infants. Chest 2001; 120: 1190-1195.

32. Moon JK, Min JK, Kil JK et al.: Clinical Usefulness of Schedule for Oral-Motor Assessment (SOMA) in Children with Dysphagia. Ann Rehabil Med 2011; 35: 477-487.

33. Tohara H, Saitoh E, Mays KA et al.: Three Tests for predicting Aspiration without Videofluorography. Dysphagia 2003; 18: 126-134.